A war ain’t a revolt, let Jamaica’s history tell it.

Tacky’s Revolt: The Story of an Atlantic Slave War (Part 1)

I was going to title this piece, “Reframing perspectives on war in the early development of Atlantic colonial societies,” but that’s too damn academic for me.

A preview of what’s to come –

Just after midnight on April 8 [, 1760], nearly one hundred Africans marched on the fort [Haldane], overwhelming the sentinel and seizing four barrels of gunpowder, a keg of musket balls, and all the small arms, numbering about forty working weapons…this lethal insurgent army prepared to make war on British slavery. Over the next several days, the rebels killed, burned, and raised across a broad swath of the [St. Mary] parish.

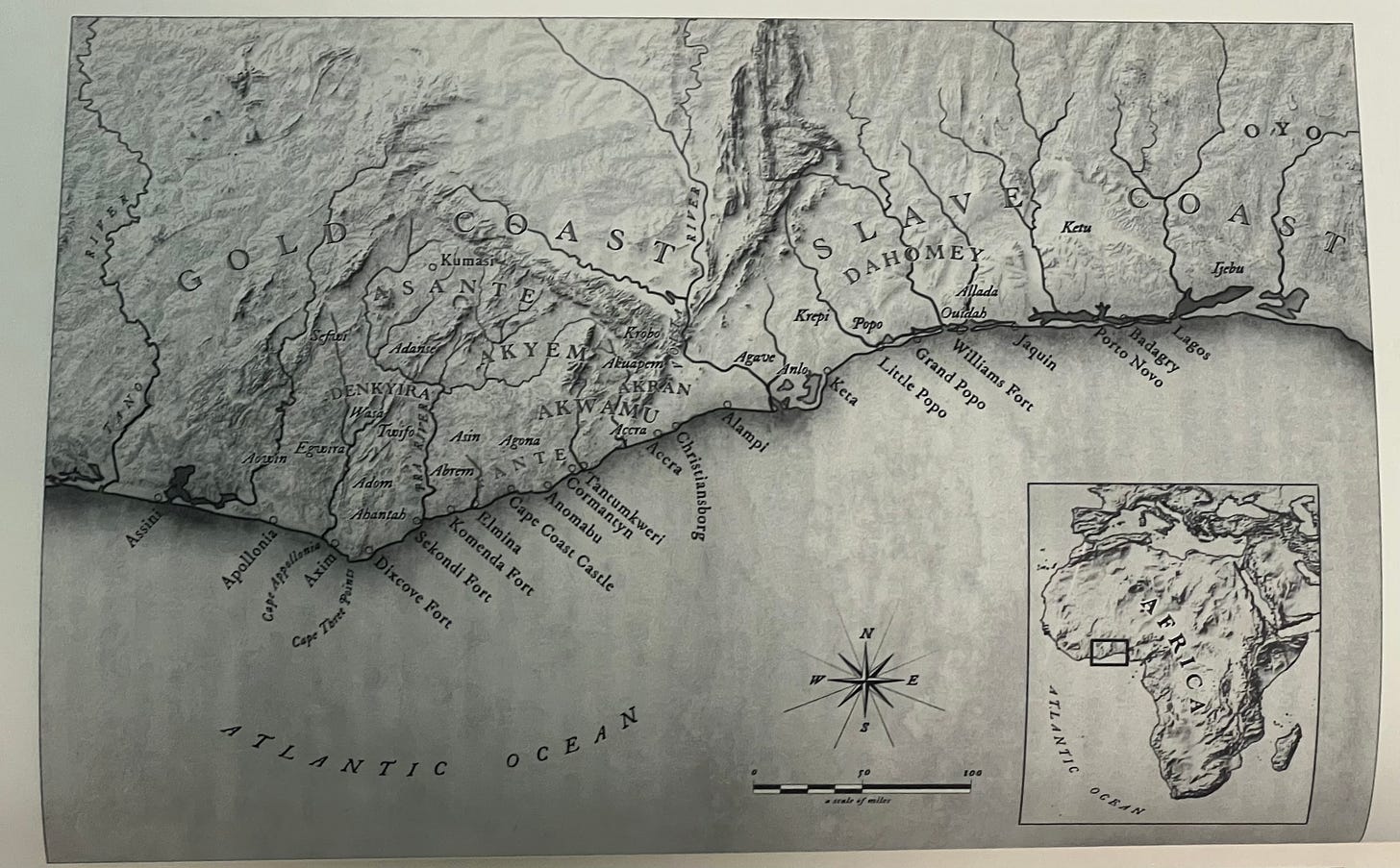

For orientation on where St. Mary parish is –

Further orientation (colonial era map) –

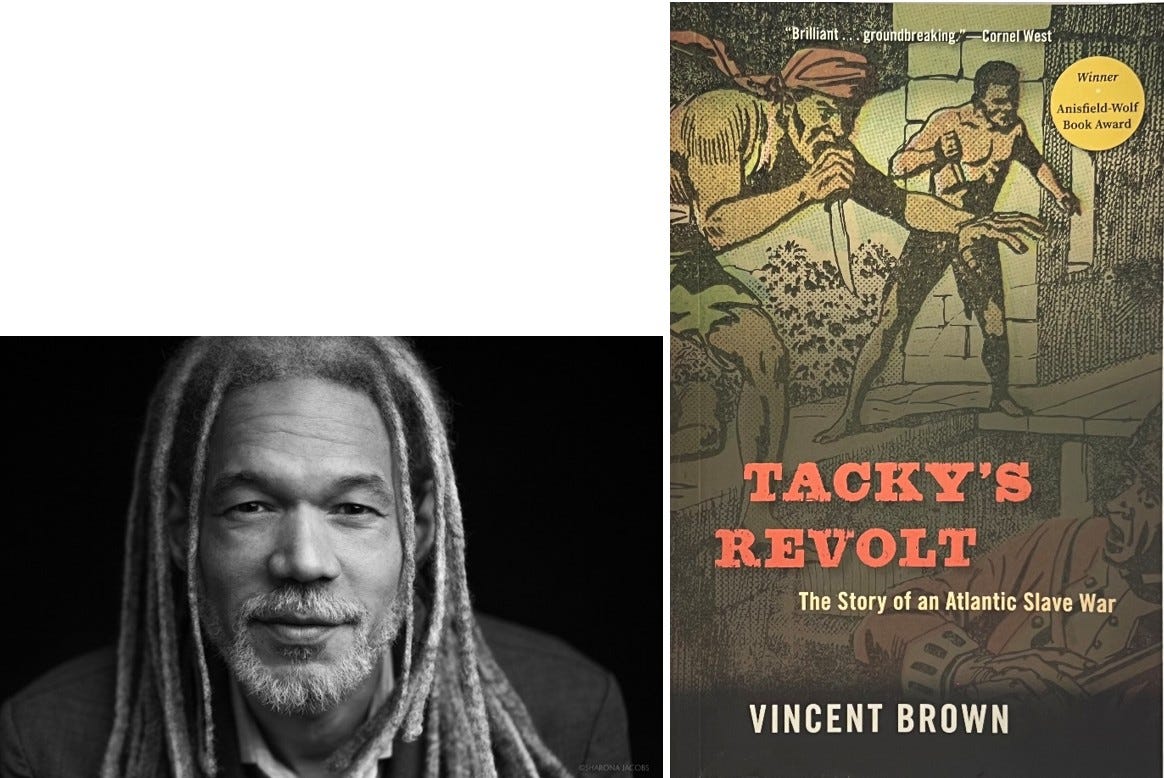

But before we get there, the author.

Vincent Brown is…someone who looks like they know exactly what they’re talking about. The full head of grey locks oozes wisdom.

A graduate of UC San Diego and Duke University, Brown currently “teaches courses in Atlantic history, African diaspora studies, and the history of slavery in the Americas” at Harvard.

Trust me, the man knows what he’s talking about.

Beware, though, this one is a big “H” history book.

It’s dense, I won’t steer you to believe otherwise. It’s not encyclopedia-thick dense. Heavy in the sense of historical names, dates, events, developments, etc., which I understand non-history lovers find more challenging to digest.

However, Tacky’s Revolt is incredibly well-researched/well-written. What I appreciated most was Brown’s complete reframe of conceptualizing what slave “revolts” and “uprisings” truly were. We commonly discuss challenges to plantation systems in the context of a failed revolt here and a fluke uprising there, notwithstanding the boogeyman of all revolts, the Haitian Revolution.

What Brown does, despite the name of the book (event), is encourage us to do away with reductionist terminology. Not for posturing's sake, but so that we can truly understand what the events were: wars. And this is to remind us that slave revolts and their protagonists are (were) treated with disdain and irrelevance. So, for now, reset yourself to think of Tacky’s Revolt as Tacky’s War.

…Tacky’s Revolt was just one episode in a much larger Coromantee war.

Historical sources are never transparent reflections of what happened, how, and why; nor, in the case of the Jamaican uprisings, are they merely the literary phantasms of the colonists’ imaginations.

It’s no secret that, typically speaking, the dominant historical narrative is told by those who wield the highest power of control via the purse, politics, etc. Calling revolts/uprisings (i.e., temporary stirs) wars would’ve legitimized the forces battling colonialism and potentially encouraged the enslaved to believe their larger movement had credence. An analogy to all the above is the Northern Ireland conflict (or, as the Irish preferred, the Northern Ireland Revolution or Northern Ireland War). In the United Kingdom, they largely referred to this tense ~40-year period as…wait for it… the “Troubles.” Lesser historical significance. One can make the connection that the British Crown is well-versed in this type of reductionist verbiage, given the nearly 300-year bridge drawn between Tacky’s War and the Northern Ireland Revolution, the latter of which I’ll talk about when I get around to reviewing Patrick Radden Keefe’s Say Nothing.

Let’s get back to Tacky’s Revolt. How did I arrive at this book?

Similar to Caribbean Rum, I landed on this text during my 2-hour-plus research stint toward the end of 2024, when I decided that 2025 would be dedicated to reading about rum’s history and its related corners.

Note: last time mentioning this fact because it will apply for (most) everything rum-related after this unless I say otherwise =)

Not a whole lot to do with rum and its crevices.

Minus the general fact that Tacky’s War did specifically target the artery of the Jamaican plantation system: sugarcane operations, and what naturally follows, boiling houses/rum distillery operations. Additionally, there’s the mention of rum serving to boost the morale of Tacky’s army vs. rum as sustenance (ration) for the British soldiers called on to quell the internal war.

The insurgents gathered together in a tree-shrouded clearing a little removed from the road, where they took stock of their provisions: pigs, poultry, plantains, rum, and other goods they had amassed from the morning raids….Food, drink, and song helped to generate the fellow feeling crucial to bolstering morale.

…provisions for the troops: “5164 lbs of Bread, 20 Barrells of Pork, 10 Do. of Beef and 31 Gallons 2 Quarts of Rum, to Carry to Natto Bay for the soldiers…”

HOWEVER, I do love when my books speak to each other. Especially when they wrestle with the other’s points, in an all-out ‘get that lie outta here’ manner. Let’s dive into some quick blips on rum and Vincent Brown inadvertently dunking on some of the points made in Caribbean Rum.

Frederick H. Smith (he wrote Caribbean Rum) discussed rum rationing to the British navy/troops, doled out by Jamaican sugarcane plantation owners. Put simply, the troops “needed” booze, and it was one of the many incentives provided to them to maintain order and control above and beyond what local militias could do when things got too testy.

Planters stored rum for traveling troops, especially during times of civil unrest. During Tacky’s slave rebellion in Jamaica in 1760, Thomas Thistlewood, the manager of Egypt plantation, broke open casks of stored rum made on his plantation… – Caribbean Rum

“civil unrest” is very different from “war.”

Though it would have maybe been out of place for Smith to include more context on Thistlewood, given the focus of his book (i.e., not on the intracies of plantation systems, per se), Vincent Brown expands on who Thistlewood really was: a serial rapist. In the context of what we’re covering here, think about Thistlewood as a larger example of what the enslaved were striking a war against, as opposed to Thistlewood simply providing rum for troops to put down a “civil unrest.” This will be disturbing, fair warning –

He penetrated the women of his choice, copulating as frequently as two hundred times a year. He devised degrading tortures, several times forcing slaves to defecate in each other’s mouths for small infractions…his diary’s descriptions of many other white men’s methods make his own seem relatively disciplined and restrained. – Tacky’s Revolt

Smith also says this of Tacky’s rebellion –

The symbolic power of alcohol is also evident in the ritualistic treatment of white victims in Caribbean slave uprisings. For example, during Tacky’s rebellion in Jamaican in 1760, slave rebels, after killing white servants at Ballard’s Valley plantation, drank their victims’ blood mixed with rum. – Caribbean Rum

That last point, Vincent Brown completely debunks, asserting that the historian Smith references drew this conclusion to bastardize the actual events and exploit the fears of white plantation owners and the British Crown more broadly.

Edwards then added that the rebels “literally drank their blood mixed with rum,” a detail presented to make the attack look more barbaric, which does not appear in the earliest account. Edwards included the detail to heighten the horror for his readers…

Brown, with a sharp eye/attention for detail, and recounting the specific sequences of events, calls into question Long’s accounts broadly, versus (seemingly) accepting the conclusions the way Smith does –

Long’s account is an unreliable guide…he offers an erroneous chronology of events. Wanting to show an island-wide conspiracy, he depicted the events in St. Mary’s Parish as simultaneous with later events in Westmoreland, extending the timeline for the St. Mary uprising and making it appear to last well beyond the Westmoreland insurrection…Long states that it was Admiral Charles Holmes who dispatched the naval vessels to the north side of the island, despite the fact that Holmes did not arrive at Jamaica until May 13, weeks after Tacky was killed and the revels had dispersed. Long surely knew this, but distorting the sequence of events in this way had the effect of making the whole affair seem that it was indeed Tacky’s revolt.

The above is purely to showcase what it looks like when my books speak to each other. Rude and poetic at the same time. I love it.

But we got more history – with the big “H” – to cover, so let’s get this started.

Who was Tacky?

Okay, this threw me for a loop while reading the book. I had to take some serious time to distinguish between the two war leaders at the center of the text. Tacky’s Revolt was started by Tacky (I know that sounds obvious, but roll with me), who I promise we will get back to at some point. I mean, we have to. He kicked this whole thing off. I say get back to because Brown focuses most on Apongo, the second leader who carried out the longer duration of the war.

Okay, so I guess who was Apongo? A Fante (like Tacky), or Coromantee (English term), and chief in Guinea who was eventually captured and sold to Captain Arthur Forrest of HMS Wager, so Apongo was renamed Wager.

This capture was ultimately part of the larger war contexts happening along the coast of West Africa, as well as the interior. In other words, New World slave revolt(s) and European conquest are squarely entangled with West Africa’s history, so that’s where the narrative must begin. Note: Rarely do narrators begin this way, which is why Brown’s work is a critical part of the historical literature on these topics. I think this is an incredibly powerful, full-context, zoomed-out reframing. One that forces the consumer to read history with an incredibly wide-eyed set of (H)istory goggles.

Under the eventful reign of King Agaja, from 1718 to 1740, Dahomey conquered coastal Allana in 1724 and Ouidah in 1727, eventually making it the most prolific slave-trading port on the African coast.

Coromantee (or Koromantyns) were known for their military prowess and were therefore stereotyped as the quintessential leaders of “rebellions” in the New World. In humanizing Apongo (and Tacky), their Old Country context would’ve made them feel it was unconscionable to abstain from waging a war against an enemy if you have the means to do so. That’s what they knew. So, that’s what they were going to do.

Apongo’s capture was an example of how Africa was indelibly linked to the larger European (in this case, British) colonial expansion. Without the wars taking place in Africa (“wars yielded human commodities”), there would not have been fertile ground for Europeans to exercise predatory kidnapping/human barter practices. In short, they fed upon inter-African rivalries –

The slave trade linked European commerce and colonial development to the political history of African wars—which produced a majority of the captives sold on the coast, both by taking prisoners of war and by creating conditions such as drought, famine, and failed government that drove people from their homes and made them vulnerable to predation. Given this tight linkage of war, enslavement, and economic expansion, the history of Africa must be understood as an integral part of the development of European empires.

In connecting who Apongo was, where he came from, the conditions under which he was transported to Jamaica, and the broader war contexts of the time, Brown establishes an organic thread. One in which we can see clearly why the former chief would have waged war on the British system. But even more, why Apongo would’ve had willing followers to back him. To defend an example of a competent military leader, identical to that which would have resembled Old World military competence. Ultimately, someone steeped in the practice of warring expeditions.

And that is who Apongo ultimately was. We’ll get back to him – and Tacky – later.

First, let’s take a further step back into…

…Coromantee territory (from a primarily political and military perspective).

Terrain: every variety you can think of. Uneven landscapes. Hard to traverse. And the neat, opposite of the last two statements. Mountainous, and some less so. These are the factors that pressed the British (and other Europeans) to stay put on the coast, to avoid the unknown, unless invited inland.

But even when invited inland, the customs of specific tribes – Angolas, Ebos, Papaws, Whidahs, and Coromantees [note: some names Anglicized to represent the British’s desire for ease of categorization] – had to be adhered to for fear of not offending and facing your demise. There’s no doubt that the British, through these interactions, took special note of who they believed would be the most suitable for their plantation and colonial supremacy ideals.

Example –

Celebrated for physical strength, mental acuity, and disciplined manners, Coromantees appealed to planters as ideal instruments of their desire to profit from a colonial settlement. The planters sometimes perceived in these particular Africans distinctive skills that would serve them well in certain specialized roles of a slave society. The nautical talents of the coastal peoples could make them ideal pilots, sailors, canoemen, and fishermen.

By the late 1600s (into the 1700s), the scale of warring conflicts along the African coast peaked, with military revolutions across the central forest region (Gold Coast) being the nucleus of it all. Aided, very strategically, by European weapons (i.e., sow dysfunction and create a natural environment where captors of war become slaves to transport to the New World), the Africans utilized their traditional weapons alongside European guns to jockey for power. The propensity to conquer entire villages/towns to supply slaves to the Europeans became a functional reality for many.

The oldest trick in the military book: divide and conquer (trade, really, conquering came much later) –

As Europeans competed for trade, they distributed guns and powder along the coast and funneled them to the increasingly militarized African communities and battlefields in the interior…With firearms lubricating the exchange…the slave trade would thrive in the decades ahead.

A rapid succession of military campaigns marked the political history of the region. In the thickly forested region that ran north from Cape Three Points, Denkyira expanded its conquests through the 1690s before the emergence of Asante at the beginning of the eighteenth century. Further up country, as the land rose through hills toward the mountain range bordering the Afram River, Asante looked anxiously from its capital, Kumasi, toward the southeast, where Akyem, rich in gold and slaves, grew in strength between two prominent ridges of mountainous terrain. These two Akan powers fought a war in 1717 that ended in the death of Asante’s founding ruler, Osei Tutu.

What’s fascinating to me, and also logical when rationally considered, is that the fluctuation in human trade between Africans and Europeans was wholly contingent on the state of war along the coast and inland at the time. The Europeans could only strike when the proverbial iron was hot, and they fully understood this reality.

European slave ships swelled with captives of these expansionary African wars. Exports of slaves from the Gold Coast spiked from fewer than a thousand in the 1650s to nearly thirty thousand during the period between 1661 and 1680 as the military revolution took hold, then dropped back somewhat for the rest of the century before leaping again to forty thousand in the first decade of the eighteenth century and fifty thousand in the second, as war engulfed the region. As many as seventy thousand and no fewer than forty thousand Africans were shipped away from the coast during each of the four decades between 1720 and 1760…Heavy concentrations of these captives originated in the coastal, forested, near-inland areas, as well as the eastern mountainous regions caught in the upheavals of the era.

Majority of these captured people went to colonies of the British (places like Barbados, Jamaica, Antigua), the Dutch (places like Suriname), and the Danish (yes, them, via the Danish Royal African Company, in places like St. Thomas, St. James, St. Croix, and most notably, what is now the U.S. Virgin Islands).

And what did many of those captured, already in a state of war (mentally/literally), do once in the New World?

Set the tone for what would become a never-ending series of wars and fortifications against challenges to freedom.

But also, examples for the many rebellious wars that would take place throughout the Caribbean.

→ 1673: Jamaican slave rebellion where “some two hundred people rose up in St. Ann’s parish…mostly Coromantines…”

→ 1678: another rebellion on an estate near Spanish Town

…in 1690, on Sutton’s mountainous estate in Clarendon Parish, the entire population of five hundred slaves rose up, set fire to the great house, and confiscated fifty muskets and an artillery piece…Colonial forces killed and captured scores in the ensuing pursuits, but hundred remain free…One of the commanders fathered a son named Kojo—called Cudjoe by the British—who would become one of the most famous maroon leaders of the eighteenth century.

→ Coromantees in Antigua killed a prominent planter in 1701

→ Saramaka maroons (Suriname) won their independence in 1762 from the Dutch after being at war since the 1690s, right through the 1740s and 1750s

Jamaican Maroons: an example of military and geographical fissures in British control of the island.

Maroon communities often operate with a degree of autonomy and self-governance with historical respect to the way their treaties were first established during colonization. A glimpse into this treaty stuff I’m referring to.

We the indigenous people inhabiting the archipelago within the North American territory of the Americas, referred to as Jamaica have reaffirmed our independence and Birthright. Our government is styled as the "Sovereign State of Accompong." Accompong Town is the Capital for Cockpit Country. We are the Heirs to the 1738 Maroon Treaty and Maroon Identification. – [current] Chief Richard Currie (State of Accompong)

Accompong Town Maroons is an example of one of the maroon communities in Jamaica –

Top of mind (for me) since Accompong Town is near where my mother hails from, in and around the Balaclava area of St. Elizabeth.

[E]ven as the colonists [British] contended with external threats, they faced a growing danger from enemy encampments in the island’s interior. When the Spanish departed the island, they left behind many of their former slaves, who had fought rearguard actions against English occupation. Called maroons, after the Spanish cimarrones (wild ones), they formed communities in the mountains, their numbers swelling from the continuous trickle of runaway slaves from English settlements, and continued to harry the new settlers. From their sanctuaries in the densely forested mountains, maroons raided the plantations for provisions, weapons, and new recruits. The presence of these free communities helped to inspire captives on the plantations, who staged several serious revolts between 1673 and 1694.

Maroon bands were governed by military and hereditary chains of command, with many sustaining their social integration via spiritual (obeah) practices. There were leaders/captains, soldiers, and general rank-and-file, which showed that their coalition-building strategies resembled what would have taken place in West Africa. A lot of the rebel encampment communities became polyglots in tribal composition (though most were likely Coromantees).

Kojo, a renowned former leader of the Accompong Town Maroons, it is said, established English as the official language to communicate/prevent misunderstandings given the diversity of origins among the ranks. Kromanti language, which derived from several Gold Coast tongues, was later adopted as a unifier.

Brown makes a very interesting analysis as it relates to using geographic knowledge from the Old World to morph Jamaican terrain to maroon advantage. In other words, it was likely that many Maroons (captured people, largely) came from mountainous, high-elevation regions, which contributed disproportionately to the early development of Maroon community profiles. Traversing familiar terrain.

And, unsurprisingly, this helped maroons fortify themselves from attack. Later, however, creole maroons (creole in the sense of native-born) had an important tactical advantage being of the land. They were accustomed to the impracticable terrain in the mountains that the British (even those of the creole variety) would’ve found impossible to scale. Hence, the untouchables.

By adapting to their surroundings, Africans and their descendants made new territories, domesticating Jamaica’s wilderness in a way that was uniquely their own.

What do you do when you can’t beat them? Make a peaceful pact so that you can still pursue your goals. And that is what the British did (i.e., what Chief Currie referred to as the 1738 Maroon Treaty). This cooperation pact resulted in Maroon autonomy, ended the first of many wars between the British and the Maroons, and granted them land and safety for their cooperation. Eventually, slaveholders began referring to the Maroons as “friends in the mountains.” Friends? Yes. And this is where the history becomes a little less romanticized given the cooperation I just referred to –

Early in 1742, some enslaved Coromantees tried to escape into the forest but were caught and returned to the planters by Kojo’s maroons. In exchange, Jamaican officials offered gifts: some cattle, five yards to each person of osnaburg (flax) cloth, and the freedom of one maroon captain’s daughter-in-law, who was enslaved in the region. The pact had passed an early test, yet Jamaica’s slaves remained restive.

As you can see, not all Coromantees/enslaved people would have been fans of the Maroons. And that is why history isn’t all that straightforward in societies that are (were) in constant states of war and violence. However, the mere existence of an autonomous maroon community within reach, especially one that got the British to cooperate, would have kept those enslaved unrelenting about the potential of freedom.

Hence, in 1744, the St. John’s Parish plot. Rebels in several neighboring plantations in Lluidas Vale went on a killing rampage, targeting black and white people, and really anyone anti-their-freedom or unwilling to join with them. Remember, people are at war.

If you’re familiar with Jamaica and are asking, what is St. John’s parish? You’re not crazy. It was abolished in 1866 and merged into St. Catherine parish (the “Lluidas Vale” piece would have stood out for the Worthy Park rum lovers among us).

Let’s now turn the page back to Britain.

The United Kingdom was a “fiscal-military state.”

Much of this effort was carried out by Britain’s Royal African Company, which held its headquarters at the Cape Coast Castle (in present-day Ghana) until that monopoly was freed up a bit into the 1700s, making the slave trade a “free market” expedition. The British were constantly at war, needing labor and more territory to fortify their initiatives. Here’s a snapshot of some major activity:

Captured Barbados in 1627

Captured Jamaica in 1655 from the Spanish

Fought a bunch of wars against the Dutch in the latter half of the 1600s (one of their main competitors in the slave trade)

…Nine Years’ War from 1689 to 1698 and Queen Anne’s War from 1702–1713 (the latter known in Europe as the War of Spanish Succession), the English, French, and Spanish worked to sap each other’s commercial strength by pillaging plantations, seizing slaves and burning buildings. Between such raids and the threat of piracy, the constant sense of vulnerability encouraged even greater fortification of trade. The English established permanent naval squadrons at Port Royal, Jamaica, and English Harbour, Antigua…

Random rum fact: English Harbour is also the name of one of Antigua’s most popular rums.

Friendly reminder that when you drink these beverages, the names' origins don’t come from thin air; they are often tied to very specific developments. In this case, an important British stronghold and military fortification. I’ve been to the actual area in Antigua, it’s beautiful. But when you’re there, you can also understand how and why it was a strategic fortification.

A view –

Can see the Spanish and French coming from every angle.

Back to the British and their constant state of warfare and colonial jockeying:

1713 Treaty of Utrecht ended Queen Anne’s War and granted the British monopoly of asiento, which allowed them to sell/supply slaves to Spanish Americas, as well as allowed them to trade on the isthmus of Panama

In effect, the British became the dominant locus of slave trading in the Americas

But contrary to popular narrative/opinion, and as you now well understand, they did not have this type of (direct) military sway on the coast of Africa.

Not until significantly later. The first establishment of trade on the Gold Coast (by the British) was in 1618, and their first fort went up in 1638; Gold traded actively before the slave trade took place in the 1660s or so. During the 17th and 18th centuries, the British were entirely at the whim of the Africans and what they tolerated. In essence, taking what they could get. Playing nice. You get the drift.

For example, paying rent to African military powers (e.g., Opoku Ware of Asante and Agaja of Dahomey), for the privilege of sitting along the coasts, setting up forts, and operating from these forts was very commonplace.

Neither [John] Cope nor any other [Royal African] [C]ompany official could envision territorial sovereignty in Africa. Their dominion was limited to the cramped forts that dotted the coast, operating in the context of surrounding towns, confederations of people beyond, and the expansive powers of the major states.

…company agents grumbled, often with good reason, that they did not always get their way on the coast, that conditions were miserable, and that Africans wielded too much power…

But, let’s be clear, when the instability was at its highest, the British swooped in and took full advantage to get in on the low and maximize their profit potential –

Between 1700 and 1750, the Akan wars helped to contribute some 375,000 slaves to the transatlantic trade. One European agent called these “delightful times on the Coast,” when traders could buy a slave for as little as a bottle of brandy.

All bets were off in the “military sway” department once the British shifted the tides to the New World.

Jamaica became, at some point, Britain’s most prized commercial entrepôt and fortified garrison. War and violence “shaped the contours” of plantation slavery, whereby the aggression of plantation operations, battles being fought to keep slaves subjugated (internally), and conflicts British engaged in with outside powers were all married and laddered up to the type of world power Britain aspired to be. Therefore, Jamaica was ruled as a “garrison government” in which military leadership and order took precedence over legislature/law. Touched on a bit of this in my Why We Drink What We Drink article, as it relates to how British pirates/privateers fit within their fortification plans. But especially how, with the support of the Crown, many military men were recipients of large land grants to set up plantations throughout the island.

We shall be governed as an army — Jamaican colonist in the 17th century

Martial law was frequently implemented for all threats (internal and external). Not so fun fact: some of the toughest Jamaican neighborhoods, which are frequently under martial law and/or some form of curfew, are commonly referred to as garrisons.

I sincerely hope that, by reading some of my pieces, you become firmly convinced that there is very little in the way of irony or happenstance, and that most things follow a historical thread where we can identify their origin. Alright, back to the topic at hand.

Britain, wars, and plantations.

Reminder: British took control of Jamaica from the Spanish in the mid-17th century. Live and die by the sword hung heavy over their heads, especially with warring factions in hard-to-reach places (call back to the Maroons and their initial wars with the British).

1 – You take by force

2 – You then, through treaties and agreements, ensure that the Maroons will not be a nuisance

3 – You continue, by force, to maintain as firm a grip on plantation holdings as possible, to continue bringing in the money and fortifying your military holdings (and, by extension, your colonies)

4 – You become relentless by throwing the weight of your laws, military, and national identity behind these aims

These “structures” will always fail, in my opinion, because they’re built on faulty foundation. It requires human capacity to adhere to a psychology that is either brutal or subservient in perpetuity. A ‘you will never snap out of this’ paradigm. Moreover, no matter how many “deficiency laws” Jamaica passed, which had the goal of balancing the number of whites with the number of enslaved people on plantations, this doesn’t account for what happens when commodity prices sour, competition makes plantation operations no longer attractive, global tides shift, etc. The power of the purse will make “deficiency laws” irrelevant when sugar ain’t in no more.

But let's return to the wars specifically (remember, they’re all intertwined), and consider the mentality surrounding those wars from the British perspective. Given that many of the white men who staffed the plantations in the formative phases of Jamaica’s development were military veterans, it was common for them to view the enslaved Africans as captured war enemies. Militarism set the tone for the style of dominance and barbarity that was demonstrated. I think this is why you’ll see in plantation history literature, across the Americas, that Jamaica served as a prime example for those who wanted to carry out the most severe forms of discipline and order. In other words, barbarity was not exemplary violence limited to specific events like internal wars. That violence was a habitual occurrence. An indoctrination. And, for those who would come later and learn from native-born whites, they were inured to the way things operated.

They are pleas’d in the West Indies with Scourging, and the first Play-Thing [toy] put into their [a child’s] hands is commonly a Whip with which they exercise themselves upon a Post, in Imitation of what they daily see perform’d on the naked Bodies of those miserable Creatures [enslaved blacks], till they are come to an Age that will allow them Strength enough to do it themselves.

Guards are constantly kept on Sundays & Holidays and the Troops of Horse in several Parishes or Precincts are obliged to Patrol in Their Respective Divisions, to prevent Conspiracies or disorders amongst the Negroes. – James Knight

…at all times to have some Soldiers Quartered in the Country Barracks to be ready on all emergencies for the protection of the out Settlements & such parts of the Island as cannot readily receive any assistance from the Towns…would be a great Security & comfort to the Inhabitants, especially those in the remote Parishes, who are now under great apprehensions both of the Foreign Enemy & the rising of their own Negroes. – Edward Trelawny

The battle was also waged on the enslaved psychologically. Symbols of military repression had to be a constant for those who were subjugated –

The Men. Of War that are constantly on the Station & the great Number of Shipping continually coming and going gives Them an Idea of the Strength & Power of the English Nation, & Strikes an awe and Terrour Into Them… – James Knight

All of this folded into the British’s motives (internally and externally) on running a tight ship to ensure that Jamaica continued to fill the coffers of the British Empire. Down to how they allocated manpower to fortify the country.

By 1760, at the height of the Seven Years War’ in the Caribbean, there were sixteen British warships assigned to Jamaica, with 478 cannon and nearly 3,700 men between them, as compared to eighteen ships in the Leeward Islands and nineteen vessels assigned to the whole of the North American continent.

The might of the sword & gun dictated Britain’s ability to maintain its colonies. This was not a new phenomenon, as there are numerous warring nations, empires, and rises/falls that we can highlight. The point here is that Britain lived by force and subjugated those it considered interests of the Crown.

Naturally, these things come full circle: nations at war are eventually met with that which they dish out.

Remember Apongo (Wager) and Forrest? Well, Forrest, after successful warring expeditions against the Spanish and others, ascended to Lieutenant of the Royal Navy in 1740. Wager was with him and sailed the ship that Forrest commanded between 1744 and 1748. What happens when the person you captured accompanies you and sees the ins and outs of your operation for four years? You give them hands-on education on “how things are done around here.” But more importantly, that you’re not invincible.

Wager also probably paid close attention to the rituals of hierarchy, the stern discipline, and the eager aggression that made the Royal Navy such a capable force. Yet, having seen sailors repelled in a battle and the Wager [the ship] wounded even in victory, he would have known that the British military was not invulnerable.

And with that, we dive into Tacky’s War…

…in part 2 =)