Opposé.

The House That Sugarcane Built + The Founding of New Acadia

In addition to distilling the authors’ incredible books, this piece will also be an exercise in juxtaposition. You will see how varied the French experience – arrival (to) and life – in Louisiana was. The first work centers a specific family. The second centers a group of people.

Note before we explore “The House That Sugarcane Built”: I’ve concluded that the closer we get to the American Revolution, and certainly anytime post-Louisiana Purchase, the further we stray from Louisiana’s heritage with rum (and cane spirits). I can also recognize that I’m human and may not be looking in all the right places. Still, we will dial back the clock in this piece, especially so with the second book, rather than pick up from the latter half of the 19th century. If you’re interested in understanding Louisiana (1) pre-Civil War, (2) during the Civil War, (3) during Reconstruction, and (4) at the end of Reconstruction, check out the following pieces:

The House That Sugarcane Built: The Louisiana Burguières

This book is a monument that says, “We Were Here, 1650–2013.” Memories reside in dusty scrapbooks, in stories handed down from generation to generation, in values, in traditions, and in heirlooms. In the end, memory is stronger than death.

…270 years of French family history.

Before walking us through the family’s start in the 1800s, the author sets the scene in early 2000s New Orleans. Ravaged by Hurricane Katrina (August 2005), and much the same for “Southwest Louisiana” one month later (Hurricane Rita, category 5), there were not many choosing to descend on “the City of the Dead.” However, on February 18, 2006, the Burguières and their extended families flocked to the city for business as usual –

…nearly one hundred Burguières family members gathered in the French Quarter at the Monteleone Hotel for the annual meeting of the J.M. Burguières Company. No matter the conditions, the meeting goes on, as it has for decades…The year has been difficult, but the clan and the company have prevailed.”

The company remains today – JMB Companies, Inc. – and is one of the oldest family-owned/operated enterprises in the state.

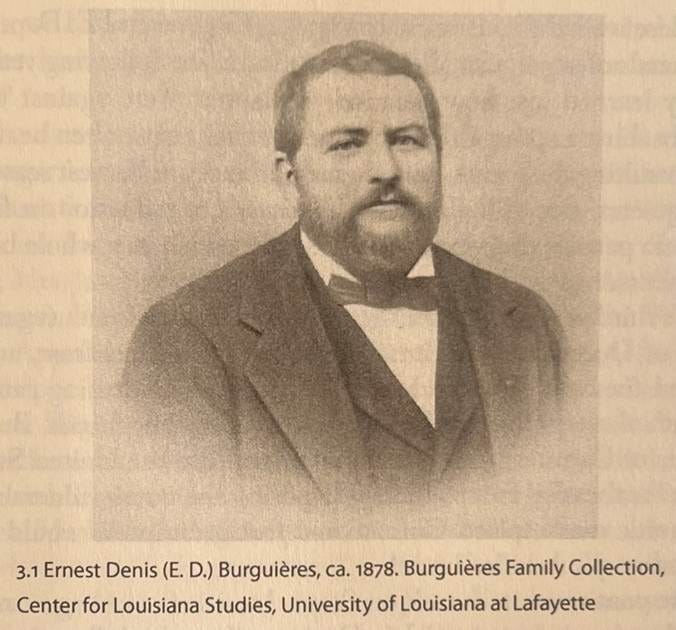

To understand the importance of the company meeting in the early 2000s, let’s rewind to the 1800s, and climb the tree from which six generations (plus) blossomed. You’ll get a glimpse of “the experiences of French nationals (“Foreign French”) in Louisiana in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.”

Then to now.

On April 29, 1831, Eugène D. Burguières (1804–76), a merchant, and his cousin, E. Denis Lalande (ca. 1808–44), a jeweler, docked in New Orleans port after boarding the ship, La Glaneuse, at La Havre on November 7, 1830. La Havre immediately stood out to me because the “busy seaway” from there to the Big Easy was referenced in The Sugar King, Leon Godchaux: A New Orleans Legend, His Creole Slave, and His Jewish Roots. The cousins’ ship was originally destined for Veracruz, Mexico (city of Coatzacoalcos), which the French colonized and granted land to French citizens who settled/built the territory. I am willing to bet that sugarcane grew plentifully in Veracruz. But the cousins saw death on the horizon, given that yellow fever and starvation plagued the territory, so they got on board the “Schooner Jane” in April 1831 and headed for New Orleans. With longstanding French control & influence in Louisiana a palpable reality, the cousins entered not-so-foreign territory. It is worth noting that Louisiana’s becoming a U.S. territory did, however, result in a flood of “Américains” into the state. The Anglo-Americans raced full speed ahead in wealth-building and commercial activities.

Historical reminders:

→ French controlled Louisiana since 1682

→ Ceded the territory to the Spanish in 1762 (“Spanish Interregnum between 1763 and 1800”), and they controlled it until 1803

→ 1803, Louisiana Purchase shifted control of the territory to the U.S.

While Eugène had “Old World Aristocracy” ambitions that he aimed to establish in this “Little Paris of America,” New Orleans was too precarious for his liking. Having seen how yellow fever ravaged the colonists in Mexico, he would not take his chances in the Big Easy. Between 1817 and 1905, yellow fever claimed the lives of 41,000 people in New Orleans. Eugène instead moved to Terrebonne Parish. If your memory sensors are activated, then you are not crazy; I referenced the parish in a prior piece (“The Terrebonne Strike”). For additional background, Thibodaux is currently located within Lafourche Parish but is also part of the larger regional area known as the Houma-Thibodaux area. Houma is the largest city in Terrebonne Parish. In the past, Terrebonne Parish and Lafourche Parish were combined into a single parish. However –

In 1822, the western part of Lafourche Interior Parish became Terrebonne Parish. The dividing line between the two parishes was east of the current boundary dividing the parishes. In the year 1853, Lafourche Interior Parish became Lafourche Parish as it is known today. The parish seat of Lafourche is the city of Thibodaux. – Thibodaux Chamber of Commerce

What’s the point? Point is: Eugène had land on his mind from the moment he left France, and so setting up in New Orleans was off the table. City life was not his destiny, landholding was in his blood –

Eugène’s grandfather…Joseph Antoine Burguières (1716–83), was a merchant and land-owner. They, like their descendants in America, were well-heeled and well educated.

This is not an unimportant point. He was cut from a cloth that valued a) landowning, b) education, and c) government work. Eugène sought to replicate that a + b + c in Southern Louisiana. He and his family were ruthlessly strategic in getting those components to work for the bloodline. Hence, his settling in Terrebonne in 1832. Note: Terrebonne is French for “good earth.”

Eugène dove right in and “began working for the local government as a recorder and notary public,” eventually becoming fluent in English. His goal was to rub shoulders with the most “influential people in the parish,” especially those of the insular French community who maintained their “fiefdoms” via inter-marrying, or “un bon mariage”. This advantageous marrying became a commonplace objective/practice among the Burguières bloodline in Louisiana.

The Burguières extended family serves as a paradigm of Louisiana French marriage traditions—marrying within the French culture, keeping the French blood pure, preserving French culture and values, and maintaining or improving socioeconomic status.

Eugène fulfilled his ‘keep it pure and ascend’ mission on July 25, 1837, when he married Marie Marianne Verret Delaporte (1812–83). The Verrets were part of the “pioneering first families” of Louisiana’s first 100 years. The other advantage he established for himself, through his work in government, was continuous land acquisition along Bayou Terrebonne (i.e., a first-mover advantage since he was on the inside). He and Marie went on to have nine children, notwithstanding the two children Marie had from her prior marriage (i.e., previous husband died). Their children would go on to also have very large, targeted families (i.e., marrying French gentry, political leaders, military veterans, people of the arts, etc.). Some of the surnames that the Burguières began marrying into were: Bonvillain, Viguerie, Dupont, and Patout.

My goal with what I outlined above is to give you the firm origin story of the Burguières family. The rest of the book follows many twists and turns as each generation carries its elders’ baton(s). Amassing bricks on top of the foundation that Eugène started. Plantations and land were purchased, and the family followed suit, becoming slaveowners and overseers on various plantations (theirs and others). All in an effort to solidify their family’s future.

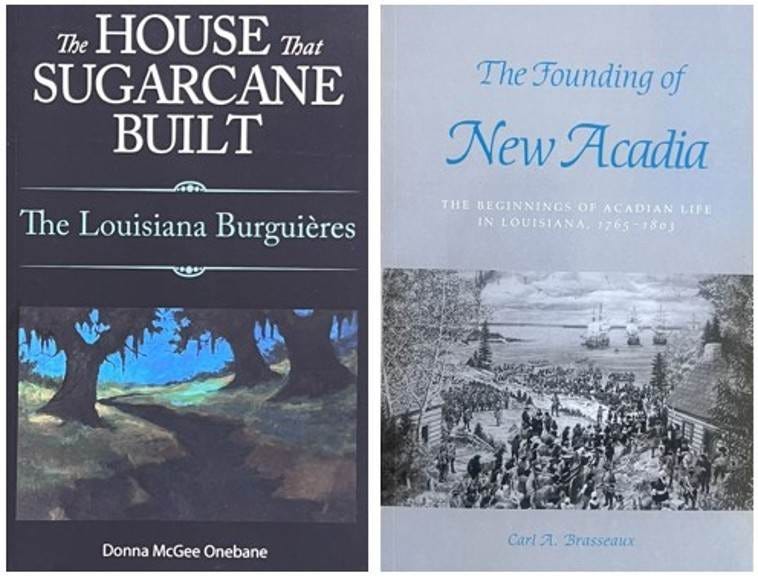

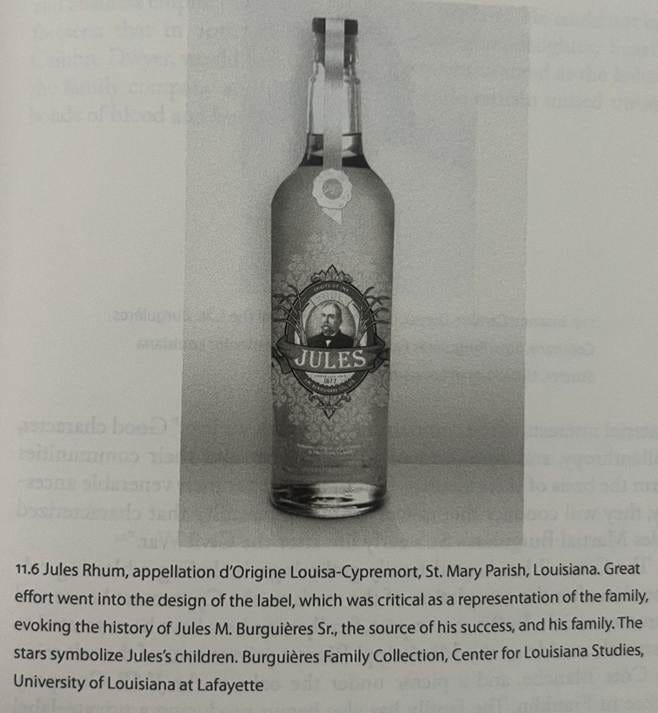

And then there’s Jules Martial Burguières Sr. Note: I’m racing through the lineage/timeline, these folks had lots of children, who all contributed to the family’s march forward. He helped the family business expand into Iberia Parish, partnering with Alphonse Bonvillain to purchase the 1,413-acre Cherry Grove Plantation. He was also responsible for creating a new entity, the one that is around today, J.M. Burguières Company. Jules Sr. purchased Cypremort Plantation, “the estate that eventually became synonymous with the name Burguières and where billions of pounds of sugar were subsequently manufactured.”

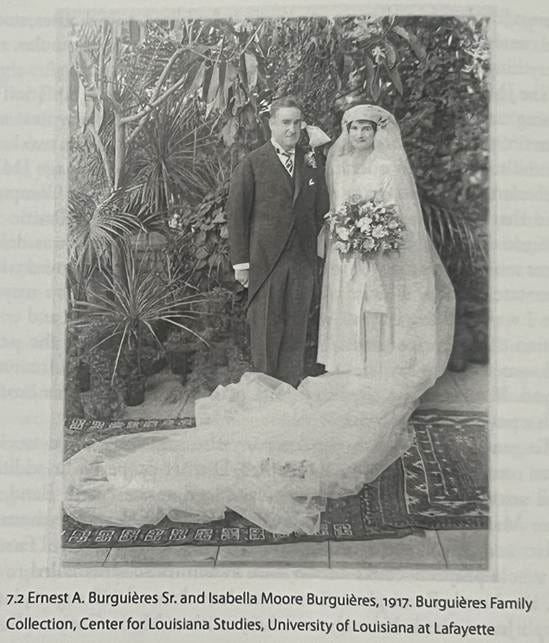

One of the most intriguing aspects of the family’s history is their geographical (and influence) shift to the state’s business and cultural hub, New Orleans. A sort of historical nod to the original patriarch: it’s safe to go there now. An alluring prospect for people who wanted to be firmly rooted in the lifestyle of the wealthy/elite of that time (i.e., exclusive clubs, operas, etc.). Even more interesting is the division and demarcations of the “Anglos” (e.g., Garden District) and the French in the city, and how this transformed over time. For instance, Ernest A. Burguières married Isabella Moore, blurring the lines between influential French families and influential Anglo-American families.

We even get to the Florida Everglades and Cuba when Jules Jr. (keeping up?) went to work for the Cuban-American Sugar Company; The family had a vested interest in building roots and influence in these areas, through speculation and getting in where the model was already proven, respectively. With this much at play, and a family tree with many, many branches, the inevitable occurred: legacy disagreements, company ownership dislocation, distribution & decision-making disagreements, and full-blown family feuds that would plague the various branches. Certain lineages would “lose their seats,” but the 5th generation did their best to maintain the peace via establishing a Family Council to better manage familial affairs.

Since 2009, Leila Bristol has been among the leaders of the Family Council. Bristow is the keeper of tradition, the storyteller, the family historian, and her untiring efforts to reclaim the family’s past and shared roots have resulted in a more cohesive clan that now includes every family line. The Council has also embraced the responsibility of preserving that information for generations to come.

Before we transition to the next book, I must admit…

…my chief concern was also addressed: r(h)um.

The Jules Rhum Project –

The family has also begun producing a private-label rum named Jules as a tangible expression of the Burguières identity.

This took me by surprise. A family rooted in French traditions, I was expecting would maintain their allegiance to wines and brandies wholeheartedly. The beverages of the Mother Country. Was this a way to differentiate themselves from their whiskey-drinking, Anglo counterparts, given that the French still had Caribbean colonies producing r(h)um? That feels a bit simple, but could be one of many nuggets. I’ll certainly be digging into this a bit more to answer the question ‘why r(h)um?’

Donna McGee Onebane.

Onebane published this work over a decade ago (2014). It seems she had the full weight and cooperation of the family in compiling the history, going all the way back to 17th-century France. Case(s) in point –

Dr. Thomas and Janice Burguières and their five daughters (Alexandra, Elizabeth, Genevieve, Juliette, and Victoria) who served dinner on their ancestors’ china, demonstrating their strong connection to family, past and present.

I appreciate Sam Burguières Sr. And Nettie Burguières for making it possible for me to interview Sam’s mother, Gertrude Reynaud Burguières, not once but twice. Gertrude was the keeper of history and tradition, and she wanted to ensure that generations to come would know about the struggles their family and company endured to safeguard their legacy.

She even met a man named Leroy Yeggins, a 94-year-old laborer who worked his entire life for the Burguières. Needless to say, Onebane pulled together an amazing piece of archival history, keeping alive the memory, or at least one example, of French Louisiana’s heritage in the Pelican State.

I’ll close out this half with her words and sentiments on the book, which also provides a neat summary of the text –

In 1851, twenty years after arriving in Louisiana, Eugène D. Burguières, French merchant and progenitor of the Louisiana House of Burguières, planted the first Burguières sugarcane crop on leased land in the hinterland of Chacahoula, Terrebonne Parish. Although floodwaters destroyed his entire crop, he persevered. In 1877, his son, Jules, purchased Cypremort Plantation. By the time of his death twenty-two years later, Jules was a millionaire, living among other sugar and cotton barons in the Garden District of New Orleans. Though he had great success and his vision was far-reaching, he could not have imagined the personal and business empire that would result a century later. He could not have foreseen that in 2010, his great-great-great-granddaughter, Susanne Cambre Dwyer, would become the first woman to stand at the helm of the family company and that his family would remain united through bonds of blood and business.

The Founding of New Acadia: The Beginnings of Acadian Life in Louisiana, 1765 — 1803

The author of this book may describe the highfalutin practices of the Creole (Louisianians of French descent, in this context) / Burguières – French wine, art collecting, and La veillée – as nothing more than tendencies of “self-styled aristocrats.” Not so much today. Well, I can’t make that call. But certainly so in 18th-century colonial Louisiana.

You see, the journey of the Acadians, or what many refer to today as Cajuns, was categorically opposite that of their fellow French speakers. We’ll soon see why and how that all came to be in their (now firm) home base of Acadiana, a mashup of the words Acadians and Louisiana.

The learnings in this book were so vivid. Truly. Felt like I explored the origin story of a group’s psyche & way of operating. Also got to rum/tafia in this text. More on that later.

“You can tell a Cajun a mile off, but you can’t tell him a damned thing up close.” – Antoine Bourque

The Acadians.

“[The Acadians live] in a manner from hand to mouth, and provided they have a good field of Cabbages and bread enough for their families with what fodder is sufficient for their Cattle they seldome look for much further improvement.” — Lieutenant Governor Paul Mascarene, 1720

A firm quote that Brasseaux opens with as a lead into the story surrounding those “Children of the Frontier.”

Helpful historical context before we jump in:

→ Acadia was established in the early 17th century by the French, before losing and regaining the territory over the decades.

→ 1632: over 300 settlers arrived to expand the fur trade and further fortify the colony.

→ Interwar among different French factions caused dislocation that the British capitalized on, seizing Acadia in 1654 (controlled the colony for 16 years).

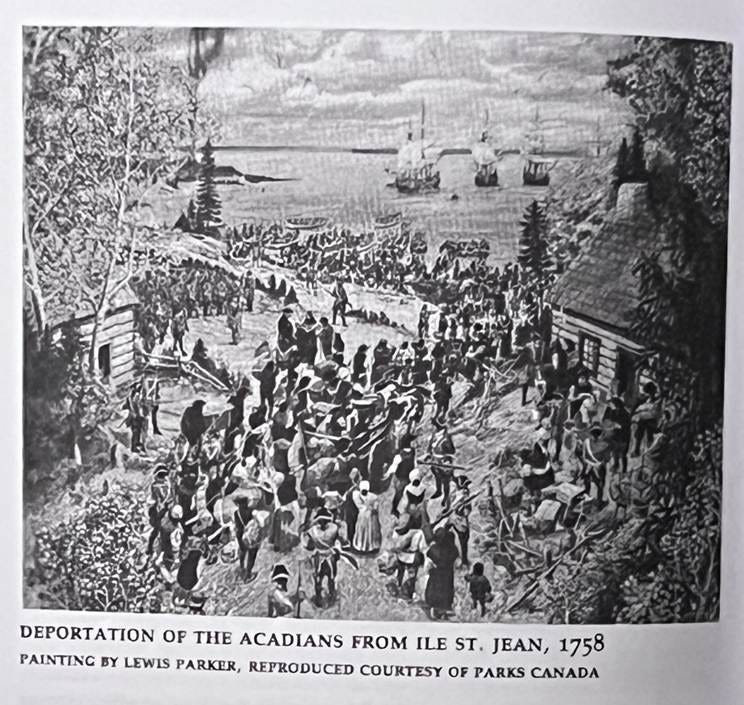

→ 1655 — 1755 was the century before “the Grand Dérangement (as the Acadian dispersal is popularly known).”

The specific “frontier nation” these Acadians were part of since 1632 was the vast wilderness of Canada.

But the Acadians’ original stomping ground was the Centre-Ouest region of France (55% of “first families” hailed from there). In Europe, the group was relegated to the peasant class, working under noble landlords. In Canada, the group was transferred over to France’s provincial administration to help build out and fortify their New World colonial holdings. Their social status, while less controlled per se, was that of “engages” (indentured servants).

Subject to the omnipresent threats of political, economic, & militaristic instability (i.e., British always on the prowl), disease, and the vagaries of a new environment, the Acadians developed what Brasseaux labels a “frontier mentality.” In other words, the Acadians social status as peasants, coupled with the “colony’s geographic isolation,” resulted in a “chronic neglect by the mother country,” causing the Acadians to develop a psyche of self-sufficiency and insularity. Other traits that the author highlights as of vital importance were “individualism, adaptability, pragmatism, industriousness, equalitarian principles, and the ability to close ranks in the face of a general threat.” Closing ranks was enabled by their extensive kinship system (aunts, uncles, and cousins everywhere).

The one caveat to this is their seeming amicability with the “Micmac Indians.” Acadians, especially in their early Canadian days, were dependent on the natives for understanding trading, fur trapping, hunting, braving the cold of Canadian wilderness/winters, gathering fish in the warmer months, and many other survival necessities. The Acadians may have engaged the natives in this way purely out of practicality: the peasants grew up under agrarianism, not in environments where they had to fend for themselves in the blistering snow.

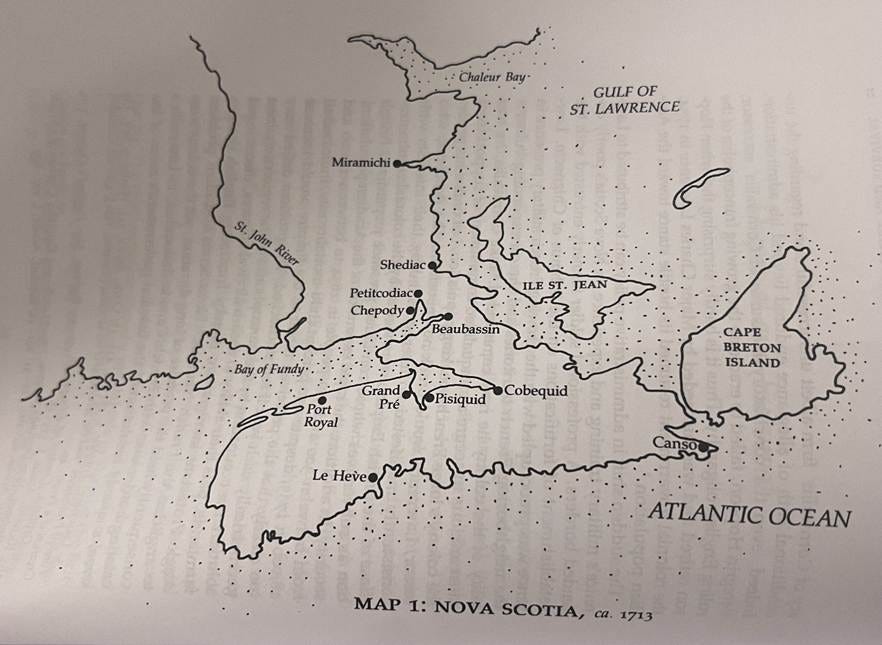

But what truly defined the prospects of the Acadians, unfortunately, was the military effectiveness of their neglectful “mother country” in its offensive and defensive jockeying against London. The War of Spanish Succession saw Port Royal (Canada) fall to the British in 1710; The Acadians engaged the British in guerrilla warfare for 2+ years until the French ceded Acadia to Britain in 1713 under the Treaty of Utrecht. It is these sorts of historical mishaps that I find incredibly intriguing. Because, after the events above, it must have been burnt into the Acadian psyche that, sense of pride/nationalism for your country, French solidarity and brotherhood, was 100% null and void under these conditions. In short, all of those ideals fall apart when your side is not the victor. What’s worse is that your so-called countrymates, who saw you as beneath them anyway, would leave you to fend for yourself, even if it was under the thumb of a sworn enemy. In short: every man for themselves.

The British promised freedom of religion (i.e., Acadians could practice Catholicism openly) to those who chose to remain in the colony. Understandably, the Acadians were deeply skeptical of that proposition since the British track record revealed that their crown required 100% cooperation and assimilation. The Acadians sought to protect their “unique blend of French and Indian folkways forged on the seventeenth-century Acadian frontier.” In the decades that followed, the British took swift action to remove the “subversives.”

November 1754: Major Lawrence & Governor William Shirley conspired to “remove all Acadians from the Bay of Fundy coast.”

June 1755: Nova Scotian governor ordered an assault on Fort Beauséjour (French fortress), which fell and sealed the Acadians’ fate since they were now “completely at the mercy of the colonial government.”

Lawrence threatened the “French Neutrals” to take a 100% oath to the crown or suffer “under the pain of deportation.”

August 9, 1755: “Colonel Robert Monckton captured between 250 and 400 local Acadians,” and began the process of forced deportation.

September 5, 1755: The Grand Pré settlers were the first to go.

Mid-October 1755: The majority of Acadians were “deported from the Minas Basin area.”

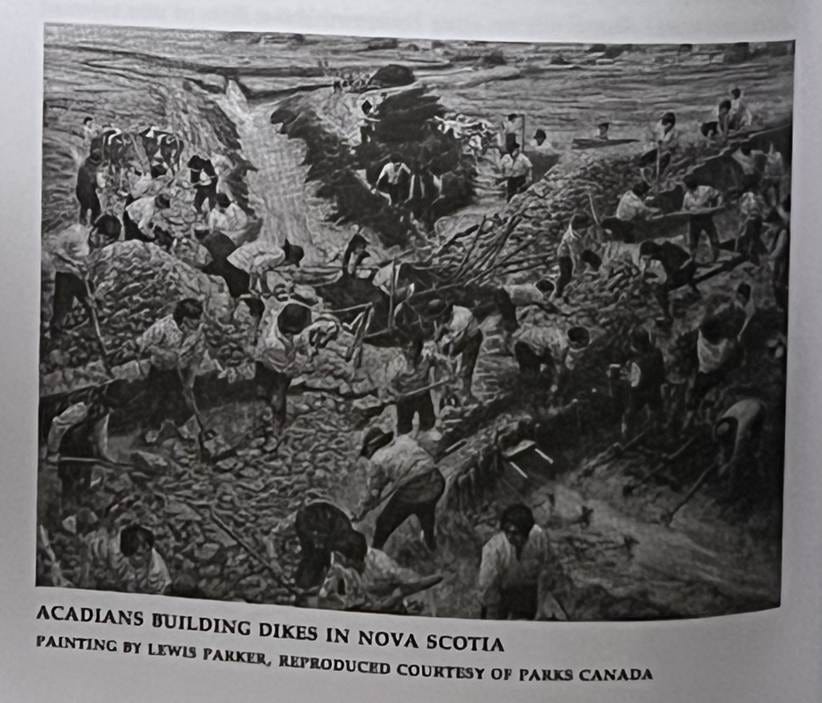

Not all were captured and removed. Some were put to work once Acadian lands were “forfeited.” The victors commissioned the helpless Acadians to build dike systems to protect properties against “the Bay of Fundy’s mighty tidal surges.” The Acadians would carry this skill set into Louisiana to fortify the land against the mighty Mississippi.

Many fled into the woods and fought to the end.

The Acadian resistance movement was centered in present-day New Brunswick, where at least 3,500 residents in the areas of Beaubassin and Cobequid sought refuge…

However, starvation soon plagued and decimated many of the resistors. Ultimately, over 5,400 people were deported to other British seaboard colonies (American Continental Colonies). Quebec’s falling to the British in 1759 signaled a de facto (permanent) demoralization among any Acadians who desired to continue the fight.

The deportations continued into the early 1760s. Boston/Massachusetts refused 1,700 Acadian prisoners that the British planned to send there in 1762, so that crop of Acadians remained in the colony until further notice. Well, that further notice came one year later –

The issue of massive deportation thus lingered until the Treaty of Paris (1763) established the framework for final resolution of the Acadian problem. Through Article IV of the treaty, the Acadians were granted a period of eighteen months to abandon England’s North American colonies for any French possession…many French Neutrals developed great interest in going to the French West Indies…No French assistance was [coming]…because the French crown had assured the British government that it would interfere in Nova Scotia’s internal affairs.

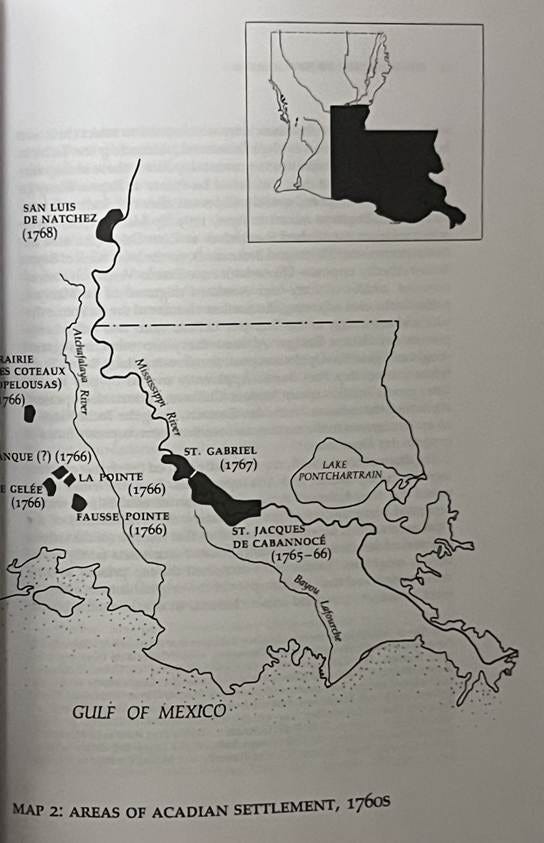

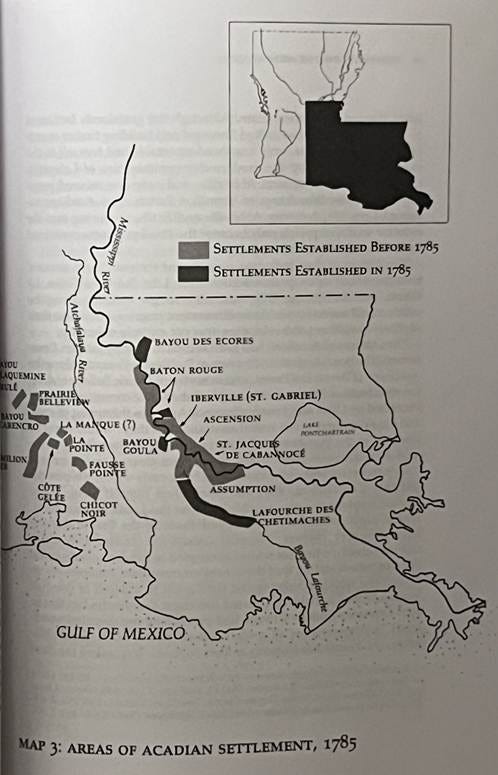

The Acadians, from my reading, were used as muscle when needed but ultimately served as strategic negotiation pawns that the French crown could deploy in times of turmoil and war. What Brasseaux makes clear is that the Acadians were steadfast in their refusal to assimilate; they’d rather rebuild in a foreign land, preferably with “their large extended families in a stable, francophone environment.” That environment, as we well know, becomes Louisiana. For some, immediately (1764 – 1765). For others, it would be a disastrously windy road, and a destitute number of decades post-Grand Dérangement before they would arrive and rekindle with their “confreres.”

Many Acadians were exiled in Maryland and Pennsylvania (British territories), which were hostile to the newcomers. The “papists” faced every accusation in the book. One allegation was that they “incit[ed] the colonial slave population to insurrection.” Here is a snippet of the English colonists’ sentiments –

“We are now upon the great and noble Scheme of sending the Neutral French out of this Province [Nova Scotia], who have always been Secret Enemies…If we effect their Expulsion, it will be one of the greatest Things that ever the English did in America; for by all the Accounts, that Part of the Country they possess, is as good Land as any in the World…” — Maryland Gazette, September 11, 1755

Some Acadians were exiled to Britain and France. Based on historical French views/treatment of the Acadians, you can guess how the newly returning peasants fared back in Europe. To be fair, there were many (surface-level but) noble attempts to resettle the Acadians. As expected, the Acadians faced the same prospects everywhere: poor crop prospects (if given land), malnutrition, begging, disease, cramped quarters, etc.

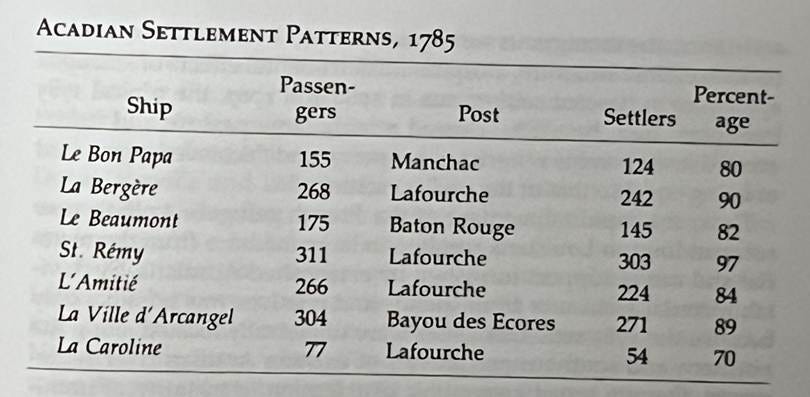

By “mid-May and mid-October, 1785, a total of 1,596 Acadians turned their backs on France, joined the seven transatlantic “expeditions,” and faced the challenge of creating a new life in Louisiana.” Or, as Brasseaux titles chapter 5, “Allons à la Louisiane (Let’s go to Louisiana).”

Like Onebane’s book, I will (kind of) stop my heavy detail overload here, and enthusiastically encourage you to pick up Brasseaux’s work so that you can understand the “cultural transplantation” of the Acadians making Louisiana home. The juxtaposition I spoke of at the beginning of the piece really comes to life when the author highlights some of the reasons the French Creoles of Louisiana and the Acadians did not operate or see each other as “confreres.” Exhibit steal your woman A, the Bertonville Incident –

The intensity of the Acadian-Creole feud can be partially attributed to amorous affairs between Acadian men and Creole women. The interest of Creole men in slave women is indicated by the emergence of a significant mulatto population along the Mississippi River during the Spanish period (1769 — 1803). Neglected by their husbands, some Creole women formed liaisons with young Acadian bachelors; such illicit unions, however, were usually detected by the cuckold husbands, frequently with violent results. One such incident involved Sieur Bertonville, a French-born surgeon, who returned home in July, 1773, to find his wife and young Jean-Baptiste Braud in bed.

Where the Acadians settled, or, rather, were initially granted land/cattle/survival supplies by the Spanish, is also of vital importance to understanding the group (then and now). For a people who cherish connection to home and permanency, for reasons that should be immediately clear, where they ended up (or desired to end up) in the Pelican State is telling. Many of those areas, it seems, are still heavily Cajun territory.

Brasseaux gets incredibly granular throughout the latter half of the book. You’ll get a taste of –

Not only where Acadians settled, but also the outfitting of their homes (e.g., what materials they were made from).

How the Cajun diet & repertoire adapted in their new land, inevitably incorporating their neighbors’ cooking practices (e.g., the use of African cooking staples like okra).

The evolving nature (and maintenance of old-school) attire across Acadian families.

Anticlericalism (i.e., deep skepticism) and a sharp eye for what they deemed the “imposition of European morality.”

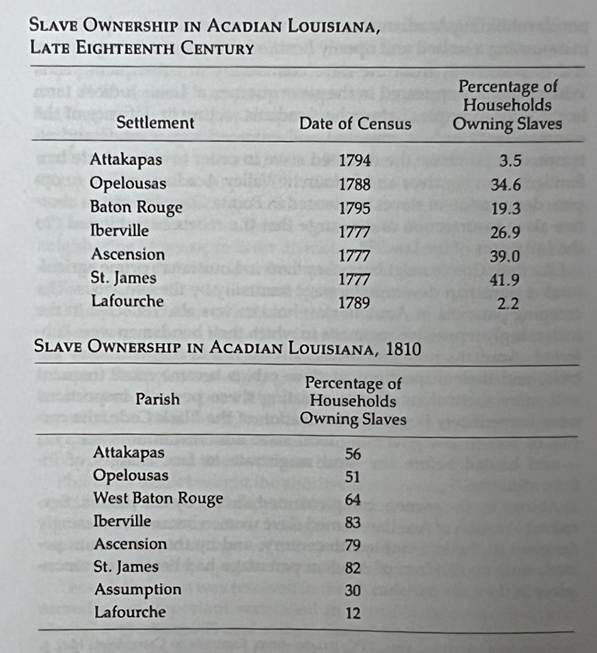

How Acadians were strategically used (by the Creole/Spanish) as the muscle via “enthusiastically serv[ing] in the local slave patrols.” Over time, the Acadians adopted the culture, practices, and ways of those Creole elite planters.

Sexual exploitation of Acadian-owned slave women became increasingly frequent in the late eighteenth century, and by the antebellum period, mulatto children of Acadian parentage had become commonplace in the river parishes.

Can’t beat ‘em, join ‘em. Ultimately, Brasseaux confirms that they adopted the default mentality of their Creole and Anglo counterparts regarding Black people: they were at the bottom. Many well-off (“genteel”) Acadians, he expands, completely shunned their heritage until it became fashionable to proclaim the Cajun flag. Brasseaux would venture to say that those claiming home-team need a bit more scrutiny (i.e., they may be perpetrating, and not truly of the original stock).

All in all, Acadian culture adopted a mentality that other Whites were to be avoided or trusted with some high degree of reservation. Home team was the most trustworthy, no matter what. Native Americans may be okay, a carryover mentality from Canada, but those ideals were largely strained and tested in Louisiana (e.g., Houma Native Americans reportedly stole their food and killed Cajun hogs). Blacks can be okay, but they are at the bottom of the social chain. Note: inherited mentalities vs. universal truths, I hope that’s obvious. At a later date, I’ll talk about the memoir of a Cajun person who affirms many of these inherited mentalities. When describing 1950s St. Landry Parish (“insular world”) –

That blacks were inferior was universally accepted, despite generally amicable personal relationships between the races, and segregation was deemed the foundation of an ideal society.

I’ll close this part with a landmark case the author opens the book with, James Roach v. Dresser Industries (July 1980):

A judge ruled that Louisiana’s approximately 500,000 Acadians “are of foreign descent” and entitled to protection under the Equal Employment Opportunity Act that prevents discrimination

The Plaintiff, Calvin J. Roach (Acadian), sued his Texan supervisor for “repeated use of the pejorative term “coonass” in referring to Louisiana Cajuns.”

Judge Hunter’s decision was merely the federal government’s belated recognition of the persistence of a francophone culture forged in the North American wilderness in the seventeenth century and tempered by foreign domination, dispersal, and subjugation, and, finally, by adaptation to life in an alien land.

If I am interpreting Brasseaux’s coverage correctly, this means that, even today, Acadians are considered a national (minority) ethnic group afforded protection under anti-discrimination laws. In other words, protective status, whether acknowledged or not, is granted under legislation such as the Civil Rights Act of 1964. In that, the judge’s ruling was a hindsight acknowledgement that Acadians were never adopted as “White” (Anglo/Creole/true Europeans). Practically speaking, those lines are blurry for reasons aforementioned. Before we go, we must address the most important beverage there is.

Tafia/Rum.

French Caribbean sugar planters also profited from rum, more commonly known as tafia and guildive. – Frederick H. Smith, Caribbean Rum: A Social and Economic History

French Canadians had lumber, fish, tar, and provisions that were much needed on Caribbean sugar plantations. In order to stimulate trade and facilitate a self-contained empire, Colbert’s policies reduced import duties on rum entering French Canadian port[s]. As early as 1685, French Caribbean rum made its way to the northern French colonies. – Frederick H. Smith, Caribbean Rum: A Social and Economic History

Outside of the well-documented connections/statistics showing colonial French Caribbean rum exports to other French territories, as well as shipments to the Mother Country, I suspect that French Acadia has some shared rum history with New England. Given that New England was the preeminent molasses importer/rum producer in colonial America, this makes geographical sense somehow. Sure, it was illegal for New England to import from non-British territories. But as we saw in John J. McCusker’s Rum and the American Revolution: The Rum Trade and the Balance of Payments of the Thirteen Continental Colonies (Volume 1), the New Englanders smuggled molasses and rum into America out of necessity.

Look at the distance. I am not convinced that Acadians and New Englanders did not share goods/knowledge rooted in rum/tafia/cane spirit production in some capacity.

For half a century prior to the Grand Dérangement, Grand Pré farmers had bartered wheat and barley for manufactured goods and specie with Boston smugglers at Baie Verte.

Whether it was the Acadians who spent a bit of time in St. Domingue before they made their way to Louisiana, or those I suspect who had a history of drinking cane spirit back in Canada, Brasseaux affirms that early rum drinking was part of the Acadian experience (emphasis mine) –

As French traveler C.C. Robin noted in 1804, Acadian Coast residents “give balls … and will go ten to fifteen leagues to attend one. Everyone dances, even Grandmère and Grandpère, no matter what the difficulties they must bear. There may be only a couple of fiddles to play for the crowd, there may be only four candles for light … wooden benches to sit on, and only exceptionally a few bottles of tafia diluted with water for refreshment. No matter, everyone dances.” But always everyone has a helping of gumbo, the Creole dish par excellence: then ‘Good night,’ … ‘See you next week.’”

Another rum reference in Brasseaux’s book –

Their [Houmas] insolence was reinforced by rum readily available from Jean-Baptiste Chauvin, a local merchant who concealed his cache of liquor in the woods behind the Assumption Parish church. By the 1780s, tribal elders complained the warriors were squandering all of their belongings, bartering them for liquor from white renegade rum runners.

I encourage you to check out Jean Baptiste Spirits, a modern-day Cajun rum producer who pays homage to the rum & tafia heritage of Acadians.

The Acadians brought cane spirit back to the “banks of the Mississippi,” I’m convinced. The issue, at least for me, is that this knowledge might be tucked away in some national archives deep in France or Spain somewhere. I’ll live with the breadcrumbs for now.

Let’s wrap with the penman.

Carl A. Brasseaux.

I am a Cajun, a direct descendant of an Acadian exiled from Grand Pré to Maryland in 1755.

Brasseaux desired to reconcile his “personal observation” of Acadian life with what was popularly portrayed and told. To unearth, critique, and explore the varying contradictions. An exercise in taking control of the narrative from a place of love for his people. During his master’s thesis process, he came across rich “material regarding the first Acadian influx to Louisiana.” This first-person information was deeply valuable to him. Those details provided the insight needed to construct a proper narrative about the Acadian migration, no more “speculation and myth.”

You wrote a damn good book, Brasseaux.

Cheers, with a glass of tafia/rum.

Louisiana, you’re something else. Good food, literally and metaphorically.

Just remember,

in all that you do, please, don’t ever stop reading.