Part C: What is Rum? (3/3)

The scientific and agricultural processes governing sugarcane’s conversion to rum is a work of pure magic.

Part C – Technical

If you have not read Parts A and B, I recommend doing so before reading Part C. I’ll warn you that this piece is the longest of the three. We’re still having fun here, but it’s a bit more involved, naturally.

Note: I am not a distiller (scientist/chemist) and will not pretend to be schooled in all its technicalities (acids and such). Bite-sized and just the right amount of information for you to identify, name, and associate the science and technology that marry to signify what rums are what (and why). Ten thousand pounds of respect to the wizards of these processes.

Some rum defense before we jump into the potion.

Let’s use logic to debunk silly accusations. There’s often talk that rum production has no rules and is a wild land of ‘do whatever you want.’ Now, based on what I’ve shared in Parts A and B (take Madeira as, quite literally, the perfect example) – to believe that rum has no rhyme or reason, you would have to assert that a spirit being produced for centuries has not improved, formalized, professionalized, or established rules for its production. Does that make sense?

Do you think this man is in a lab coat, with all of those gadgets, playing ‘do whatever I want’ games?

In my intro article, I briefly discussed Geographical Indications or GIs (designation and specifications identifying a product as that country’s product). Here is Madeira’s GI and Certification process. Tasting panels. Specified production requirements. Weighing cane. Cane juice only. “Therefore, and based on the no. 3 of the article 7 of the Regional Legislative Decree no. 18/2021/M, IVBAM prepared an internal regulation that sets out the minimum organoleptic requirements that the product entitled to the Geographical Indication (GI) Madeira Rum must present.” What the hell does organoleptic mean? The point is — you can’t be reasonable and say that rum has no rules. Every country that produces rum defines its rules very carefully. Most are standardized to worldwide spirit industry requirements (e.g., minimum 40% ABV / 80-proof to be classified as rum).

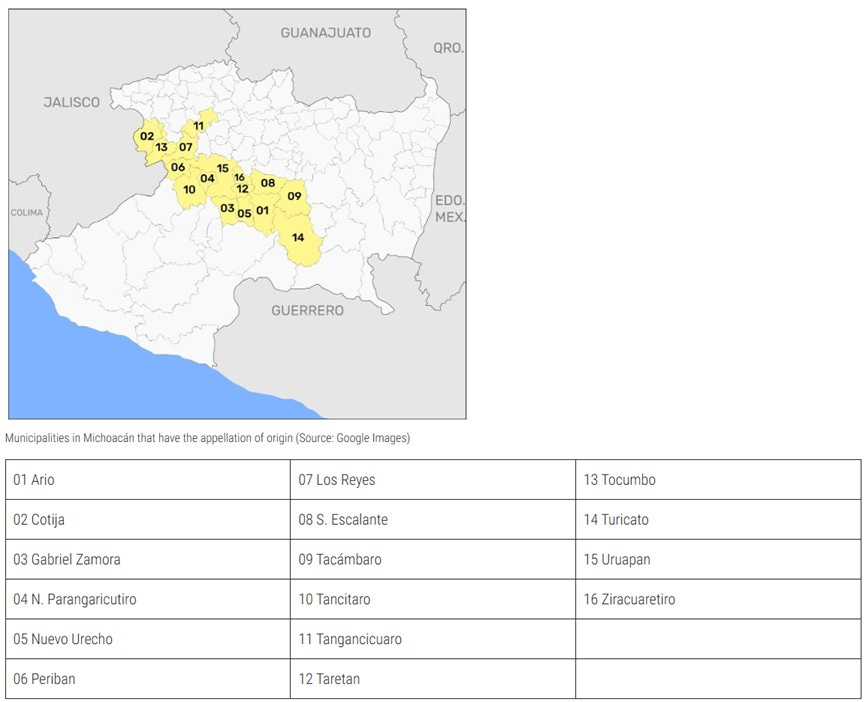

I’m going to hammer this ‘rum and governing rules’ point home. Charanda, a Mexican rum, has incredibly strict guidelines.

“Charanda can only be made within 16 municipalities in the western Mexican state of Michoacan because it developed there. With a history dating back to the 16th Century it’s a very long and well established tradition which was recognized with a legally defined appellation in 2003.” – Flaviar

“A Denominación de Origen (Also known as Denomination of Origin, Denomination of Control Origin, Geographical Indication, Appellation D’Origine Controlee, etc) is a protection granted to products that demonstrate unique and traditional characteristics of a specific geographical area, passed down from generation to generation, and influenced by certain natural factors. It is a recognition obtained through evidence and documentation that validate its authenticity and the impossibility of replicating it elsewhere in the world.” – The Rum Lab

“Understanding DOC of Charanda is a sugarcane distillate that carries the meaning of “red land” in the local language. Its production is characterized by the use of spring water from the high mountains of the region, ranging from 1200 to 3000 meters above sea level…The importance of the designation of origin for Charanda lies in its protection and preservation as a culturally rooted product with centuries-old traditions. The designation of origin ensures that this sugarcane distillate, which has been cultivated in the region for centuries, is recognized and respected as a cultural and traditional element.” – The Rum Lab

Tradition dates back centuries. Artisanal production. Undeniable specificity. Can only be made in a specific region of a specific country to legally be that product. We’ve seen these types of rules before, it’s a matter of whose products get recognized, why, and if you have the wallet, influence, or are geo-strategically important enough for your designations to be taken seriously.

In America, the Alcohol and Tobacco and Tax Trade Bureau (TTB) collects taxes and enforces regulations on alcohol, tobacco, firearms, and ammunition. Therefore, recognition of spirits and their rules in the U.S. is guided by the TTB. The TTB recognizes Brazilian Cachaça “as a type of rum and as a distinctive product of Brazil.” Charanda? Nope. The most the TTB says on rum is: fermented sugarcane by-product —> distilled at less than 95% ABV —> bottled at no less than 40% (that’s it, source). Is Jamaica’s rum Geographical Indication, which blows this minimal requirement out of the water, recognized by the TTB? Nope. Is Guyana’s GI recognized? By the EU, yes, but not so by the US. The EU doesn’t recognize Jamaica’s GI either, though. Okay, what is my conclusion from all of the above? *Licks finger and holds it to the sky for an answer*

Brazil puts the B in BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa). Disclaimer: I’m not a hater, so Brazilians – don’t interpret any of this as a dig. You’re the only source I can reference in this analysis. The only thing I hate is…that I haven’t tried Cachaça yet =/

“Today, BRICS countries are home to roughly 3.3 billion people — over 40% of the global population. The BRICS economies also account for an estimated 37.3% of global gross domestic product based on purchasing power parity.” – World Economic Forum

Look, coffee (I’m sure) is far more important to Brazil’s GDP/agricultural export contribution than Cachaça since they are the world's largest coffee producer. However, whatever trade agreements were struck between Brazil and the US back in 2012-2013 had to have included Cachaça in the basket of goods/designations that were to be recognized for their Geographical Indications. Why? If you “matter” geopolitically and geoeconomically, it is far more likely that your Geographical Indications will be recognized by the U.S. That’s my unemotional and non-insider analysis. In other words, if you say “recognize this or else,” and the U.S. starts busting out with laughter, it’s a long climb to the recognition-top for that country’s product.

But you know what? You know who else puts the B in BRIC(k)S? Skillibeng.

Seriously though, American rum producers get punished because of these actions. The TTB, for other American spirits, has rules/codification down to navy seal-level regimentation. Even if America wanted to say “US-first” vs. all those other rum products, it could technically do so. That action would not be an ounce of shock to the rest of the world. But as it stands, Cachaça 1 – Louisiana Rum 0. Leaving tax money on the table for a home-grown product that could be so much more successful is, I would argue, extremely un-American. Note to reader: Louisiana grows A LOT of sugarcane and has a deep history of rum production. This is also a self-fulfilling prophecy. Your “stuff” won’t be world-class if you look down on it, don’t support it, don’t patronize it, and, in the context of the TTB, don’t regulate it.

My fellow Americans, a vote for me would be a vote for American rum *thunderous claps while I executive order the minimum drinking age to 18*

Note: Recognition of GIs gets very, very political. Exhibit A (or “ah” as they’d say) x French Rhum Agricole: who recognizes the Appellation d'Origine Contrôlée (AOC), the hooblah around tradition/historical use of the term Agricole, recognizing that the French are going to go to the end of the world to protect their spirit interests, etc. Exciting stuff, but ultimately, in my opinion, a distraction. What’s in the bottle? That’s what matters.

Let’s transition to how the beverage goes from cane to glass. A lot of this will feel familiar to you if you’re knowledgeable about the distillation and aging of other spirits. And it’s no secret that your familiarity with how a beverage is made can enhance your sensory perceptions and appreciation of the product.

Raw Materials: the agricultural heart and source of rum

Sugarcane by-products – syrup, juice, molasses (where it all starts)

As you saw with Charanda, there are nuances depending on location. Not only does the sugarcane have to be from the specified regions, but they also have an additional cane juice by-product they use, “piloncillo (solidified sugarcane juice)”

Historically, molasses and cane juice have been the dominant by-products used in rum production (molasses more so). But a notable exception to this rule is Haitian Clairin (Kléren). The Haitians not only use non-hybrid/heritage cane, harvested by hand and transported by animal to the distillery, but they also focus heavily on using syrup and juice (note: very few producers in the world use syrup). And let me tell you, oh my goodness is Clairin good! (source: Clarin, The Spirit of Haiti). Example below.

If you read Part B and the word “guildive” from the video stood out to you, then your brain is connecting the dots: colonial era, predecessor name for rum: kill devil (English) —> guildiverie (French rendition)

It’s all connected! And so beautifully done

But what’s most beautiful is the benefit that flows directly into the community (jobs, income resources for cane farmers, etc.)

Big up to

ma cheriemy Zoes

You can appreciate how enamored people become when trying to distinguish between a rum that is juice, syrup, molasses, a blend of two, a blend of three, etc. And some get much more excited about this than others. I’ve read that Hawaii has over 50 different cane varieties, likely from their location (cane’s walk from Melanesia to Polynesia). Undoubtedly, the Hawaiians would tell you to “hold my beer rum” if you wanted to get into a back and forth on different types of cane.

Long and short of it is – the cane variety makes all the difference in the by-product’s taste. What’s more, the soil and climate that the cane blossoms in also make a major difference (i.e., volcanic soil vs. non, mountainous/colder regions vs. non, high elevation grown cane vs. non, etc.). Apparently, most rums are produced from the cane variety Saccharum officinarum, which sounds like a Harry Potter spell.

“As ingredients are the basis of any spirit, a healthier, cleaner agriculture will result in higher quality rum. And this is perhaps more important than the sugar cane variety used.” – Luca Gargano

Perhaps I’m getting out of my wheelhouse here, so, an image —

Water (no magic happens without it)

I find that this can be a fly-by point when people are discussing rum production, but the water source is ultimately critical to the taste of the rum. Water is used to mix with the cane-by products, dilute it in the case of molasses, to get optimal sugar content for the yeast to do its work in the next phase (Fermentation), and to remove impurities as a pretreatment. Water is also used throughout the process to cut the strength of the rum (legal and taste purposes).

In other words, rainwater, spring water, “limestone filtered water,” water from a river (as is done in St. Lucia) will all have varying impacts on the flavor profile of the end product.

Speaking of Saint Lucia, let me get back to making points about the rum space (note: what follows will make more sense if you read Part A). Let’s pay homage to Margaret Monplaisir, CEO of Saint Lucia Distillers –

Fermentation: come here, Raw Materials, let’s turn you into alcohol

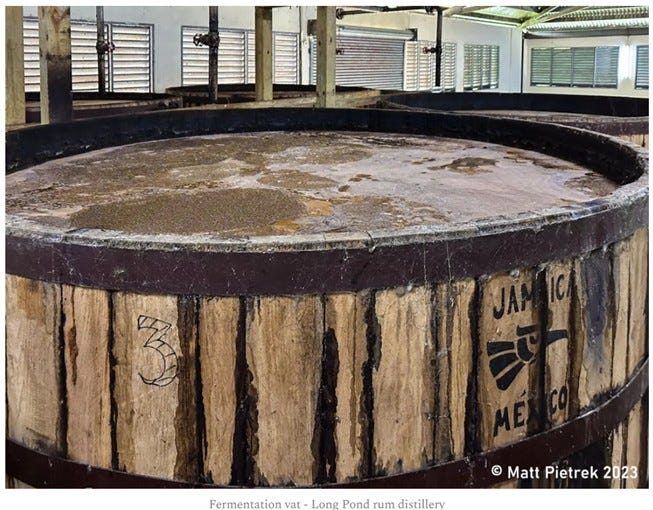

After the sugarcane by-product(s) and water mixture do their thing, yeast – a fungus – attacks the mixture, feeding on the sugars and converting it to ethanol (alcohol). Voila, sugar gone, alcohol in, albeit at a low level (7%-10% ABV). This all happens in fermentation tanks/vats which are temperature controlled (heated up) at around 75°F and 86°F (24°C and 30°C), plus and minus. Some rum makers, like Antigua Distillery Limited, assert that “wild yeasts are unreliable, so a special strain of commercial yeast is used for making rum.” (Some) Jamaican producers would say – “what are you talking about?!” And this, friends, is the beauty and reason rums from different places will taste differently.

“The wild fermentation process is the key to the unique aromatic profile of Hampden Estate rum thanks to a very high level of esters. It follows ancestral techniques from the 18th century, only using the native, ambient yeasts present at the distillery.” – Hampden Estate [Jamaican]

It gets very involved when discussing Jamaica and fermentation, but this is a hallmark distinction point for the island’s rum compared to others. In addition to Jamaicans fermenting for much longer periods (up to 3 weeks sometimes vs. others being a few days), the “extra ingredients” Jamaicans may sometimes add to the fermentation process/tanks ultimately give their products a unique taste. For a brief overview of things like dunder, muck, cane acids, and esters (all happening/added during the fermentation process) and how they’ve become staples of Jamaica’s rum taste, check out

’s article on Substack. Lots of science involved here.

Distillation: come here, fermented wash (alcohol), let me concentrate you into some high-proof potion

Raw materials and fermentation are so critical to the taste profile of rum, no doubt, that’s the foundation of what influences the entire process. But many focus on distillation as the crux of distinguishing great rums from good and bad ones. There is a staple figure and company in the ‘great rum’ (in)dependent bottler/distributor world, Luca Gargano/Velier, who feels strongly about distillation’s impact. Gargano has even gone so far as to create his own classification (worth the read!)

“If one were to classify all existing types of rum there would be a huge number of variables to consider; they would need to be differentiated based on ingredients as well as fermentation, distillation and aging techniques, with each of these four areas being divided into several different sub-categories. However, all of these variables take a back seat compared to distillation. Even the best ingredients and fermentation technique would see their benefits obliterated by industrial distillation, which mainly extracts ethanol and causes the loss of any non-alcoholic substance from the - albeit excellent - ingredients and fermentation process.” – The Gargano Classification

Many (read: a lot of his producer-clients, in particular) follow his designations to the letter, noting “Pure Single Rum” on their bottles. Ultimately, the producers do this to highlight their artisanal/high-quality product since Gargano started this Classification to “distinguish craft rums - rich in different substances besides alcohol - from industrial rums, which mainly contain ethanol.”

Luca when he went to Martinique for the first time in the 1970s — “I was 18 years old, and it was my first time in the tropics. The parties, music, girls, palm trees, little frogs, rum – I fell in love immediately.” (CEO Magazine)

Boldened the ones he really wanted to highlight; the others were throwaways (e.g., little frogs). Respect!

You’ll see Luca in Haiti (reasons: Providence Rum & Clairin)

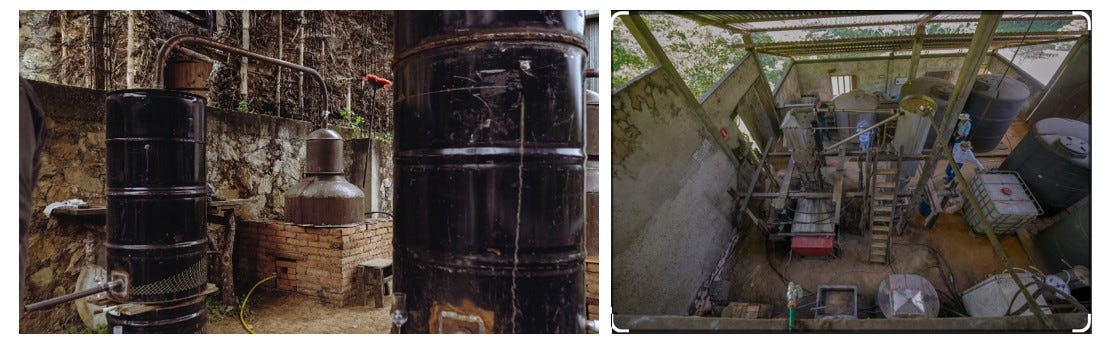

Like most spirits, rum is distilled on copper pots (OG-style) or column stills. “But the rum world opens this up with wooden stills, double retorts, batch stills and more…various distillation methods used around the world, creating a multitude of different rum styles.” (Black Tot Rum)

(Double Retort) Pot is considered batch distillation because a certain amount (batch) is allowed at a time to be distilled before cleaning/re-batching (slow cook) –

“Batch distilling with a copper pot still takes about 8 hours for 1500 liters and requires constant scientific & artisan organoleptic monitoring – checking for volatile compound separations with a hydrometer and sensory review for flavor & aroma. The interaction of distillate with copper neutralizes the acids and sulphur, “softening” the spirit. The traditional copper pot still design is actually very inefficient – in a good way: it allows persistence of congeners – the unique character flavors we look for in rum.” – The Real McCoy

Column Stills –

“…the early 1800s saw the first continuous distillation devices from inventors like Celier-Blumentahl, Coffey, and Derosne. These devices, also known as column stills, could operate nonstop for many days and were more energy efficient. A spirit distilled using a column still costs a small fraction of the same spirit if pot distilled.” – The Colours of Rum

You’ll find that countries formerly colonized by wine and brandy nations (France, Spain and Portugal) tend to use column stills when producing rums, more so than former British colonies (historically speaking). This is largely because those formerly colonized countries, previously hamstrung by restrictions on production in favor of the continental heritage spirits, were essentially playing catch up to the British-controlled territories (i.e., becoming major producers, increasing their export market share, etc.), and could now do so effectively – in the 1800s and beyond – with the column-still technology producing more at a fraction of the cost. Not to mention, column stills produce lighter-body rum compared to pot stills, which would have been favorable in the wine and brandy countries since those populations were used to lighter-bodied distilled spirits. Today, distillers utilize column stills based on economies of scale/finances, taste and blend desire, what they want to be known for, and a host of other practical/profile factors.

A very notable exception to the rule (there are many): Alambique Serrano, Single Origin Oaxacan Rum. I cannot wait to try their stuff.

They use the “Krassel-Still,” which was invented by the patriarch who started the business, Max, in the 1930s –

“It houses eight plates in the distillation column, produces no heads or tails, and the distillation ABV is regulated by the temperature of the cooling chambers and the flow of the fresh caña juice to the boiling chamber. It is an engineering marvel that needs to be seen to fully comprehend. Unlike the majority of Oaxacan aguardiente producers, the Krassel Family fires their still with diesel, rather than use the much more common method of powering their still with firewood. They believe this to be the best way to protect regional forests, which are increasingly threatened by deforestation.” – Production

They also – more recently – began using rustic Copper Alembics (pot) which are typical of mezcal production in the Oaxacan Valleys (higher proof, heavier rums)

Heads and tails? Boiling chambers? Fair questions. Let’s talk about what is actually happening in the machinery. What is the distillation process? The amount of homework I did to understand this…learning is never dull.

During distillation, you take the fermented wash, put it in one of the previously mentioned stills, turn on the heat, and watch intensely as the alcohol and flavor molecules in the fermented wash are separated from the water as they vaporize. These separated vapors are collected and condensed back into liquid form where the concentrated acids, alcohol, oils, flavors, etc. (separated from the water) are more present. This all works because alcohol boils at a lower temperature than water (hence turning on the heat). This also is way more complicated/involved. And to the science people we say – thank you for your work.

Now, the alcohol that we’re interested in that evaporates in the process is ethanol. But no process is perfect, so other “bad stuff” is also leaked into the process. Things that, if consumed, can kill you. Most are just unpleasant tasting. My bad that was a bit dramatic. The folks over at Black Tot Rum do a great job at describing this, so I’ll quote them directly –

“Heads - represent the very first alcohols that will evaporate from the fermented wash (as they have the lowest boiling point). In the heads you’d usually find methanol, as well as more solvent smelling aromas. You will also however get esters at this stage, which for many rum lovers is an extremely desirable part of the distillation!”

“Hearts - After the heads have evaporated, the next section to evaporate is the ‘hearts’ - this is the part which contains ethanol, and will be used for bottling, blending, or ageing - this is the drinkable part of the distillation!”

“Tails - Once the ethanol has evaporated, the distiller will make a cut to separate the hearts from the rest of the alcohols left in the wash, which are generally known as the tails - these contain all the heavier, oilier components such as fusel oils.”

“It should be noted that even the heads and tails still have their uses and can be either recycled into the next distillation, or small amounts used in the overall blend of rum to add certain flavours or aromas to a distillate (without adding so much that it becomes unsafe or undesirable). Where a distiller makes their cuts, and how much of these heads and tails are repurposed into the distillate or incorporated into the final blend, will vastly affect the flavour profile of the rum.”

Conclusion: We mainly want the hearts. I’m pro-recycling so I want the heads, too...because of esters (flavor)…moving on.

Once all the cooking/stewing/separating of Heads, Hearts, and Tails, which takes place at hot-as-hell temperatures (I’ve seen 170 degrees Fahrenheit to 190 degrees Fahrenheit), is complete, the mad(ly intelligent) scientists take the rums off the still, and we have beautifully unaged (clear) rum ready to be consumed.

Discussions of stills are widespread among distillers because, outside of industrial-style production methods, there’s a truly fine-craft element associated with types of stills and each company’s method-to-their-madness. Some, like Demerara Distillers Limited, have legendary still-status, which adds to the allure of the rums they produce, and is a testament to what many would consider a unique flavor profile –

“Demerara Distillers Limited benefits from being able to operate the last two original Wooden Pot Stills in the world. Over 250 years old and originally used to produce the Demerara Navy Rums…The Double Wooden Pot Still originated from the Port Mourant Estate, founded in 1732, and was later moved first to Uitvlugt and then in 2000, to Diamond.” – El Dorado

While unaged rum is a beautifully crafted spirit, many producers move on to the next stage of magic to keep their product lines robust.

Aging: come here, high-proof alcohol, let’s give you color, wood flavor, and a different character

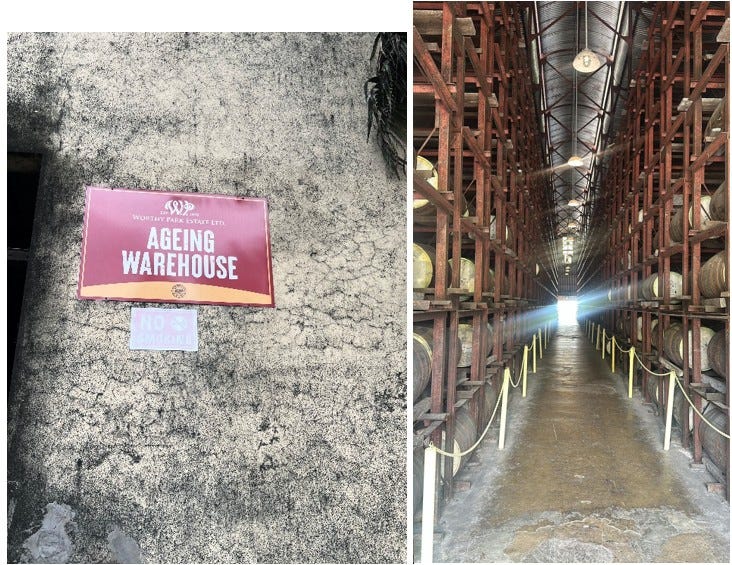

Simply put – taking the unaged liquid, putting it into barrels, and letting the character of the wood give the spirit more than 50% of its flavor and color. Timeframes range from a few months to a few years to upwards of 21+ (wasn’t a drinking-age joke, I’m highlighting the Appleton 21). If you have a chance to visit a distillery, you will undoubtedly see the barrel warehouses and smell the amazing aromas of liquids aging/vanishing.

I know I started this with “Simply put,” but as you can probably tell – rarely is anything in this world ever that simple:

“Tropical aging outside the original distillery may be acceptable, but distillery aging is always preferable. We demonstrated this by aging several Neisson casks in different places in the same distillery. As it turned out, the same spirit made from the same sugar cane and fermentation batch, aged in the same type of cask and even in the same distillery in small storage areas only 50 meters apart produced very different rums due to differences in average temperature-to-humidity ratios. This is further evidence that terroir makes a dramatic difference.” – Luca Gargano

Everything held constant, the “same” rum tasted completely different when the barrels were placed ~164 feet apart given the difference in “temperature-to-humidity ratios.” Fascinating.

Another important distinction there, though, is tropical aging vs. continental aging.

“Continental Ageing refers to the process of maturing Rum in the European climate, which is distinct from the tropical conditions where most Rum was initially distilled. The climates in Europe are typically cooler and more temperate, with fewer temperature fluctuations and less humidity. This method of maturing slows the interaction between the Rum and lowers the evaporation rate in the barrel, creating a gradual maturation process. Cooler temperatures lead to less evaporation (called ‘angel’s share’) and a more controlled ageing environment.” – E&A Scheer

Translation: tropical and hotter climates (typically more humid) cause the liquid in the barrel to extract and hug the oak more, leading to a more rapid absorption of flavor and color, as well as a higher evaporation/loss of liquid (angel’s share) than what would happen in a cooler climate. Those typically cooler “continental” climates, which have sharper variations in weather patterns, cause the liquid to contract more often in the barrel (i.e., sitting flat in the base of the wood vs. constantly expanding). Trade-offs. Gargano would say that the end product is not its purest (craft) liquid if not aged at origin…even at a specific place at that point of origin. Again, fascinating. The barrel game is robust. You have some spirit makers who toast, char, or engage other “treatment” methods before putting the liquid in to wake up some of the flavors that will be imparted from wood to liquid.

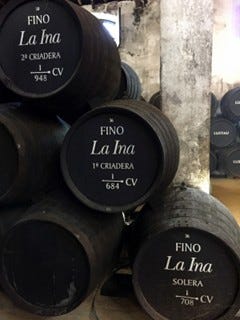

A notable aging tactic worth mentioning is the “Sistema Solera,” a style of aging originating in the Spanish Sherry industry. What happens during that process: barrels are stacked on top of each other in a pyramid structure, all different ages —> oldest liquids on the bottom (solera) are fractionally extracted and poured into the youngest liquids (barrels at the top) —> creates a constant blending of younger and older liquids in successive fashion while the oldest are constantly extracted for bottling.

I’ll bet you 1 Guatemalan Quetzal if you correctly guess which rum-making countries primarily engage in the Solera aging method. Congrats, I’ll break you off USD 0.13. Speaking of Guatemala (c’mon, you know I have to), let’s pay homage to the Master Blender and Solera-aging extraordinaire, Lorena Vásquez of Zacapa –

Again, this will make way more sense if you read Part A.

The most common barrel used in aging – worldwide – is ex-Bourbon American White Oak; Bourbon ain’t legally bourbon if not aged in a new charred oak barrel. Once used, anything put in that already-used barrel can no longer be classified as Bourbon, which creates a massive cooperage industry that repurposes those barrels and sends them out to the rest of the world. Hence, ex-Bourbon barrels are the most commonly used for aging rum, notwithstanding the vanilla and oaky notes that have become more desirable for aged rums. But as you’ve well come to understand by now, exceptions abound for a myriad of reasons: who has what relationships with what producers/cooperages, what profile of rum do you want to produce, do you want to be well known for your cask-choosing and experimentation, do you have a special cask program where you do secondary aging/maturing in other casks, which no doubt creates a revenue-engine for those producers of things like cognac (probably one of my favorite second maturations), port, sherry, calvados, etc. While I’m sure there are blueprints and precedents, the distillers and blenders who are masterminds at this are truly remarkable. To take different cane by-products, maybe even blend them, and then say let’s use this cask for this number of years and then put that liquid in a cognac cask (for example) for a few months and then produce really good liquid…wow. Some purists would say that long aging destroys the rum’s base characteristics and taste: Too much barrel work and not enough appreciation for the distillate. That’s a personal preference. I encourage you to taste widely – unaged to long-aged – and decide for yourself what you like.

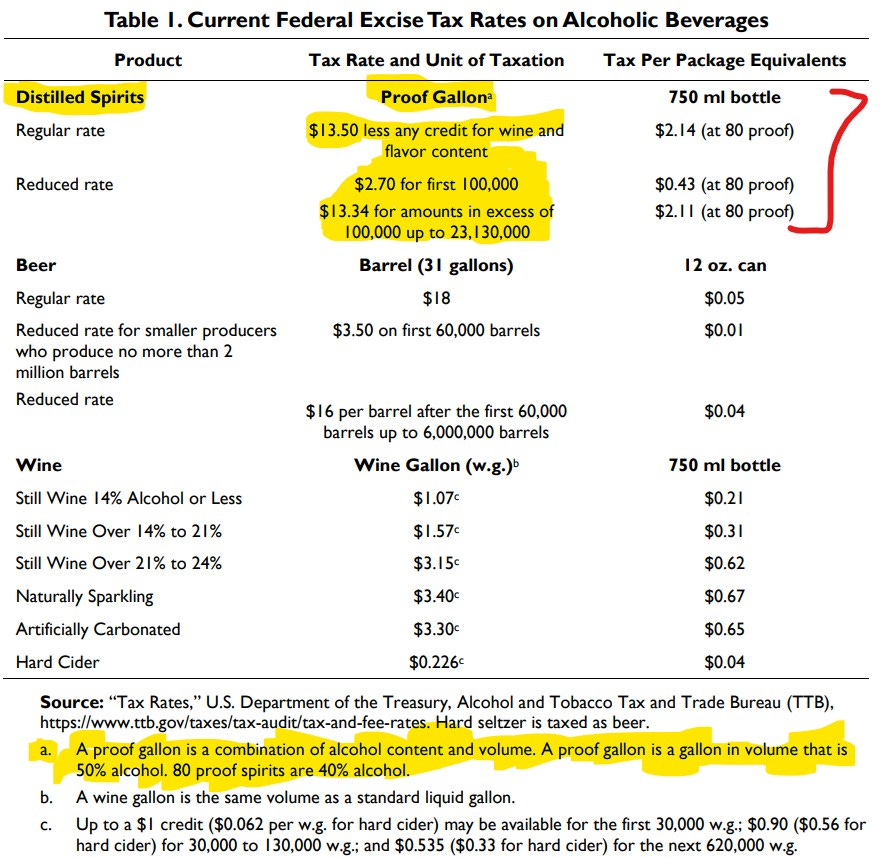

On the topic of long-aged rums, they are pricier. Better? That’s up to your taste buds, but undoubtedly heavier on the wallet. Why? Because most tax governing bodies worldwide require taxes to be paid on aging liquids every year. If a spirit is aged for 21 years, that producer will pay taxes from years 0 – 21. And, as is the case with most industries, the producer passes that tax on to distributors, who then pass that on to retailers, who then pass that on to you (or some variation of that). So, that truly is why you’re paying higher amounts for longer-aged spirits: It’s a burdening cost to producers that they share with consumers. The combination of 1) tax liabilities and 2) loss of rum (angel’s share) all factors into why longer aged rum is more expensive. Entrepreneurs, or anyone who has run a payroll, will have deep empathy for the above facts. Not making money on a product for 21 years when you need to meet payroll obligations every 2 weeks (for most)…yea. You can appreciate that this business requires a heavy chunk of change to survive.

Remember, I gave a lot of airtime to using former bourbon barrels, but there are always exceptions. Here Brazil, showing you some love for my comments earlier –

“Spirits aged in oak...taste reliably like oak. But there are more trees in the forest and Brazilians have spent the last few hundred years figuring out which ones make cachaça taste good. There's bálsamo, jequitibá, cabreúva and more, each with their own flavor. We age Nossa for one to three years in casks made from sustainably-harvested amburana wood.” – Nossa Cachaca

“taste reliably like oak” + “there are more trees in the forest” are in intense level of institutional-shade.

As you’ve noticed, from fermentation to distillation to (maybe even then) barreling, loads of flavor are cooked up and manufactured by producers, artfully so. It is for this reason that descriptors like “dark,” “light,” and “gold” to describe rum is incomplete. Historically accepted and something consumers have become accustomed to, it then becomes a self-perpetuating cycle. But “dark” rum, to me, sometimes signifies that coloring or other additives have been put in the rum (spiced rum seems to be a favorite among people). But adding sugar to rum, now that you know what you know, sounds a little, uh, unnecessary maybe? Again, these things are done to sell products in a way that companies believe will resonate most. And, mostly in the US, rum has come to be associated with “sweet spirit,” which doesn’t translate in many other parts of the world where sipping rums (no additives, sugars, etc.) are very common. And that is why, America, a vote for me would be a vote for…alright, I’ll stop. Conclusion: I don’t know what dark (aged?), light (unaged?), or gold (lightly aged?) really means. I do understand why it captures consumer attention and wallets, I do. I love a good, “pure” cut rum. Nothing needed/added except love and maybe some time (in the barrel).

Last little nuance on barreling and age (statements): they’re either straightforward for non-blended rum (i.e., 8 years), or, for blended rums, the youngest in the blend is usually how people reflect the age of the rum (i.e., a blended rum of 8 years can have a 12-year-old rum in the blend, but they legally/typically will list it as an 8-year-old blended rum).

Some think it’s all a distraction and you should focus on the quality of the liquid –

“The heart of Chairman’s Reserve is the emphasis on blending which the late “Chairman” Laurie Barnard instilled in his team and who continue to carry out these techniques today. Laurie believed that the best rum could not be achieved in a single barrel but instead could only be accomplished by blending various components together of different ages, styles, finishes, and raw materials. For this reason, you will find no age statements on our products. Instead, we choose to accentuate the expertise and innovation exemplified by our “Art of Blending.”” – Chairman’s Reserve

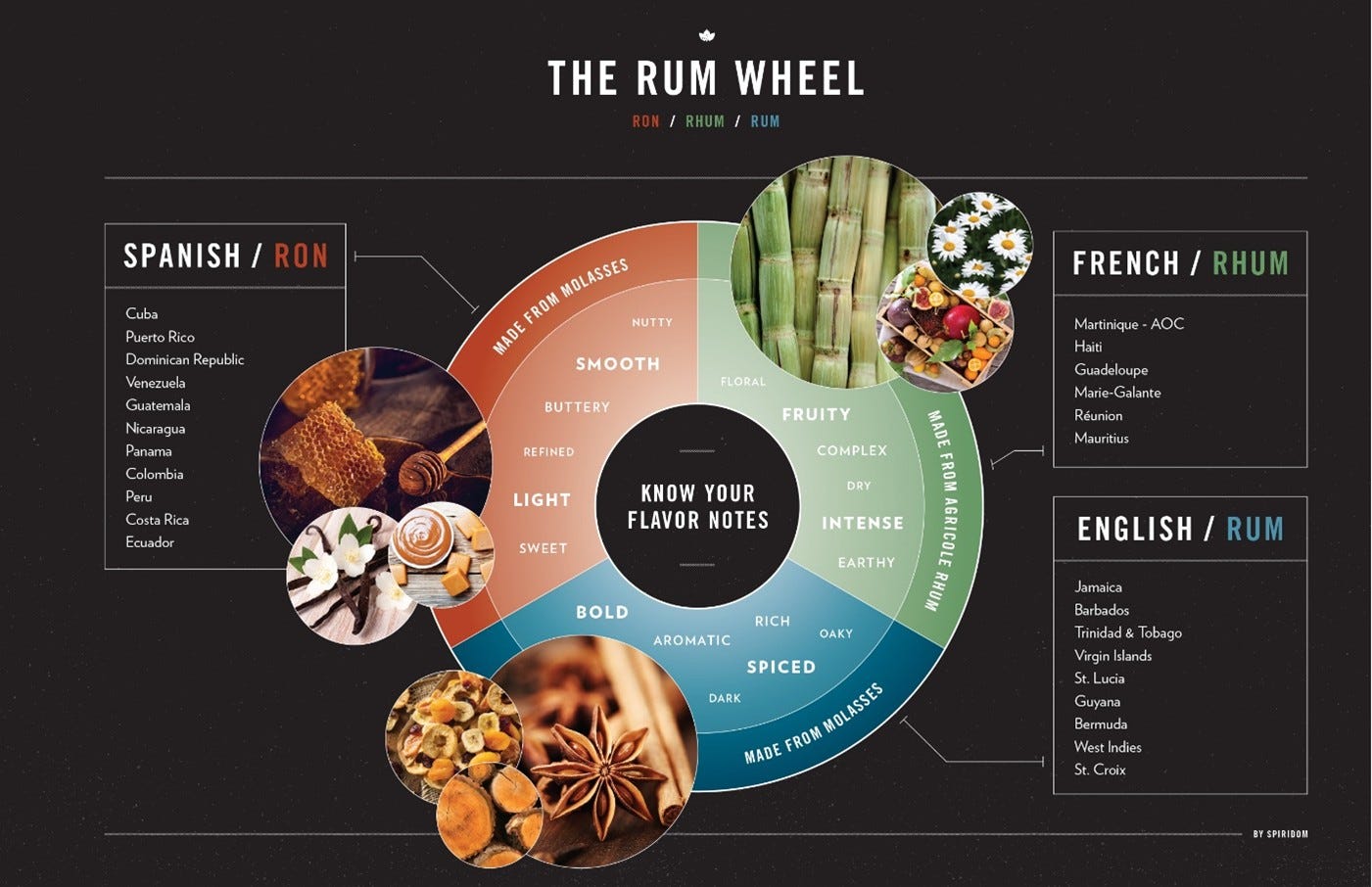

Alright, I’m going to go on a bit of a “classification” analysis (rant). I’ve noticed that people in the rum world, and sometimes people who have a loose understanding of rum, take the 1) harvesting of sugarcane/use of certain by-products, 2) choice of still/technology, 3) choice of other factors (barrel usage, proof, etc.), and 4) (most important) former ruler of the nation in question to bucket rums into English-style, French-style, and Spanish-style. Notwithstanding some islands, such as Martinique, still being overseas regions or fully under the domain of the French, so I believe all of their bottles are legally required to say “Product of France,” most other nations are no longer part of the British or Spanish empire (for instance). This is not to do away with the deep history, contributions, and legitimate associations with these former imperial countries, the reader in me doesn’t like conscious omission of details, give it all to me. However, the “former-ruler-style” designation is reductive and incomplete for most countries. These should be historical footnotes, not the dominant and primary way to describe rums from certain places, it’s fairly lazy. But more importantly, if we’re calling a spade a spade, the classification is an institutional way of reminding certain rum-producing nations that they are economically and politically insignificant to do much of anything about it. I don’t think this is being done consciously/intentionally, it’s more become the norm.

Put differently, I would never call, nor does anyone ever refer to Louisiana rum as French-style-American rum. Or, more simply – just French-style rum. I guarantee you will not be treated kindly if you ever looked an American whiskey lover in the face and said, “oh, yea – this is Scot-Irish-style American whiskey.” This is not a secret, everyone knows who influenced America’s drinking habits and love of whiskey. Some even pay direct homage: Makers Mark notably spells whisky without the “e” to show respect to Bills Samuels Sr. and his family’s Scottish ancestry (Maker’s Mark). You know what they don’t do? Claim that it is a Scottish-style Bourbon. That even reads a little funny, right? These things are very important historical truths, but footnotes, my friends, not the entire character/profile of the beverage. Please let certain countries have some dignity to classify their beverage simply as “name of that country-style” rum. I’m not one to go to war over words and symbolism that don’t have net-positive impacts on people’s lives, but I think we can agree on this one. The Spanish left Venezuela (as an example) back in the 1800s. Let them call their rum Venezuelan-style rum.

Things that have become normal – especially with language – are hard to correct overnight, but I think certain things are more straightforward than others. Even though I loved the book Caribbean Rum, the author made some missteps with characterizations like –

“For similar reasons, Appleton estate rum is one of the few British Caribbean rum makers to highlight the plantation complex.”

There are Jamaicans of British descent, but that’s not the statement. It’s to denote Appleton rum as a British-style rum. Too simple. I otherwise highly recommend his book.

Remember, I am not saying to abstain from educating yourself using these foundations. But understand where these classifications come from, why they exist (the history is fascinating!), and why these designations are both informative and incomplete. That’s all. But don’t run away from knowledge. Run toward it.

ABV: the strength of that rum, as measured in alcohol content

Worldwide standards around this are straightforward at this point.

ABV (%) = Proof x 50%

40% alcohol by volume = 80 proof alcohol

80 proof alcohol is the global (unrecognized, by any global body) standard for what constitutes the minimum ABV to be considered a spirit

While it is likely/historically accurate that this proof is rooted in what was deemed taste-appropriate, the perfect balance of alcohol and flavor, this has way more to do with taxes now

I am stretching these sub-bullets into the neverland. But yes – most alcohol is 40% ABV because it’s cheaper (pay less taxes) to produce. Some things are (now) more practical than technical.

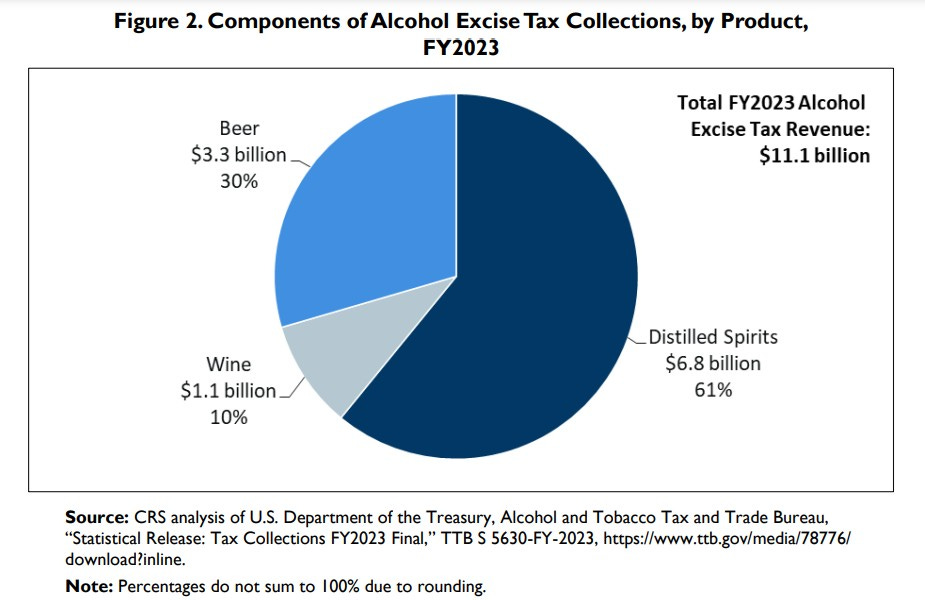

“Since their inception in 1791, federal excise taxes on alcohol have been imposed or increased primarily to fund emergency spending during wartime or in response to concerns over the growth of budget deficits…Over the next two centuries [primarily post-Whiskey Rebellion of 1794], alcohol excise taxes were reimposed, raised, and repealed, often surrounding periods of wartime.” – Congressional Research Services

Translation: Proof it above 40 if you want to, Uncle Sam is getting his cut. Why? Thirty billion for di account e o!

I know that I initially said this was straightforward. But I don’t deal in the straightforward (boring), rarely is anything that black and white. And because the world is grey, there are exceptions to the rule (reminder: read this in the context that there is no global governing body for spirits and designations. Countries typically accept/deny individual countries’ rules for what their spirits are).

Call back to our friends over at Alambique Serrano

“Cartier 30 is an unaged rum produced in the town of Santa Maria Tlalixtac, Oaxaca… Distilled from fresh cane juice, the name refers to a specific level of alcohol measured on the Cartier scale, which eventually fell out of use in favor of the alcohol by volume. 30 on the Cartier scale translates roughly to 70% abv and was the preferred strength for many folks in the village, where historically it’d be mixed with a bit of fresh cane juice and shot.” – The Company

Let’s scramble the brain a bit. In the EU and in (their ex-girlfriend’s land) the UK (source, UK), rum’s ABV floor is 37.5% (not 40%). They even go as far as saying – “Rum shall not be flavoured.” Scrap the “u” from flavored and we are in agreement, lads.

Blended vs. Non-Blended Rum: does the rum have multiple parts that make it whole, or is it straight like that?

“Single Blended rum, a unique case in the world of spirits. As some distilleries have both continuous columns and batch stills, Single Blended refers to rum produced in a single distillery by blending different types of rum from both continuous and batch distillation…” – Gargano Classification

Based on everything I’ve shared with you, at this point, you read that and knew exactly what Gargano meant. Let’s deal with blended first because non-blended is straightforward (that word again, I promise it is). Blends can be rums from different countries (multi-origin or multi-country blend). Blends can be rums from the same distillery, but different marks/distillates/methods (column and pot, all pot but different marks, etc.). Blends can be solera (old and young mix). Blends can be different casks (first aged in a bourbon barrel and then second aging in a sherry cask). E.A. Scheer blends. Their sister business, The Main Rum Company specializes in sourcing/importing rum, continentally aging it in Liverpool (single cask), but I’m sure that some of what they receive from distilleries are also blends.

And non-blended is the opposite of everything I just mentioned. I suppose that, while non-blended (for some) would be considered the purest of the pure, it’s probably inefficient for producers not to squeeze everything they can out of their production. Therefore, many lean on blending (more efficient). It’s all tasty, either way. Keep doing what you’re doing.

A parting message.

Barring religious, health, financial, and/or belief considerations, I encourage you to drink rum, full stop. If you can’t, engage in its mother raw material, the sugarcane (very vegan). If you can, approach the spirit with worldwide curiosity. Try broadly for the adventure, maybe you’ll hone in, maybe you won’t. I find that a lot of people who go on a rum-adventure realize that it won’t ever cease, they can’t ever tap the ceiling (read: create that much space in their passport). I don’t doubt that you’ll land on a country, style, or even cane by-product rum that you prefer (“go-to”). That’s natural. In the process, remember that these beverages are best enjoyed with strangers, loved ones, lovers and friends. And with that, Usher, take it away.

#rumresponsibly