Tom Standage — A History of the World in 6 Glasses (Part 2/2)

This second half is the sober but jittery close out – coffee, tea, and Coca-Cola

Coffee, that drug beverage we all love to start the day with.

As you know, a coffee link-up with a classmate put this book on my radar. And there’s good historical precedent for why that is unsurprising. In the late 1600s/early 1700s, scientists, philosophers, and thinkers (I always find this a funny categorization) began to reject old notions of how the world worked (i.e., fixed, pre-determined), opting for reasoning, direct observation, and experimentation. I personally think that part of this is directly related to exposure vs. random sparks of intelligence. In other words, colonial conquests exposed Europeans to new possibilities, ways of doing, eating, living, etc., which is one of many reasons that caused them to say, “Hmm, maybe things could be different.”

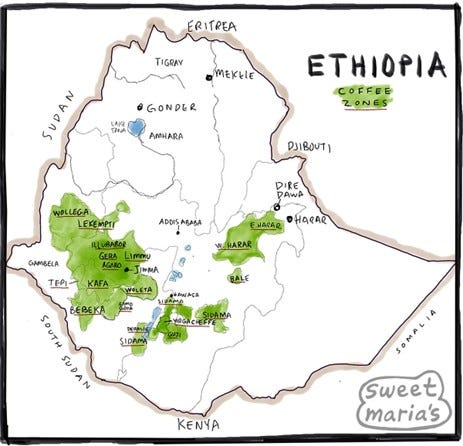

This Age of Reason + Enlightenment Period + Age of Exploration was, in part, fueled by the Ethiopian OG beverage, coffee –

Out went dogmatic reverence for authority, whether philosophical, political, or religious; in came criticism, tolerance, and freedom of thought. The diffusion of this new rationalism throughout Europe was mirrored by the spread of a new drink, coffee, that promoted sharpness and clarity of thought. It became the preferred drink of scientists, intellectuals, merchants, and clerks—today we would call them “information workers”—all of whom performed mental work sitting at desks rather than physical labor in the open. It helped them to regulate the working day, waking them up in the morning and ensuring that they stayed alert until the close of the business day, or longer if necessary.

Note: Standage says that coffee originated in the Arab world, which confused me because I’ve always read that coffee originated in Ethiopia and then spread to the Arab World (Yemen first). Or he may be suggesting that “Kofy” blossomed fully in Yemen, unclear: “While coffee berries may have been chewed for their invigorating effects before this date, the practice of making them into a drink seems to be a Yemeni innovation, often attributed to Muhammad al-Dhabhani, a scholar and a member of the mystical Sufi order of Islam, who died around 1470.” Someone more knowledgeable on that fact can chime in and help us out.

In addition to being the “great soberer” and drink of “clear headedness,” likely self-prescribed characterizations of distinction relative to their drunkard European brethren, coffee was a practical beverage. Because it was made with boiling water, it was a cleaner alternative in a time when contaminated water was commonplace. It seems as if coffee’s march was as follows: Ethiopia —> Yemen -> —> Arab World (Mecca + Cairo) by 1510 —> Europe by the 17th century.

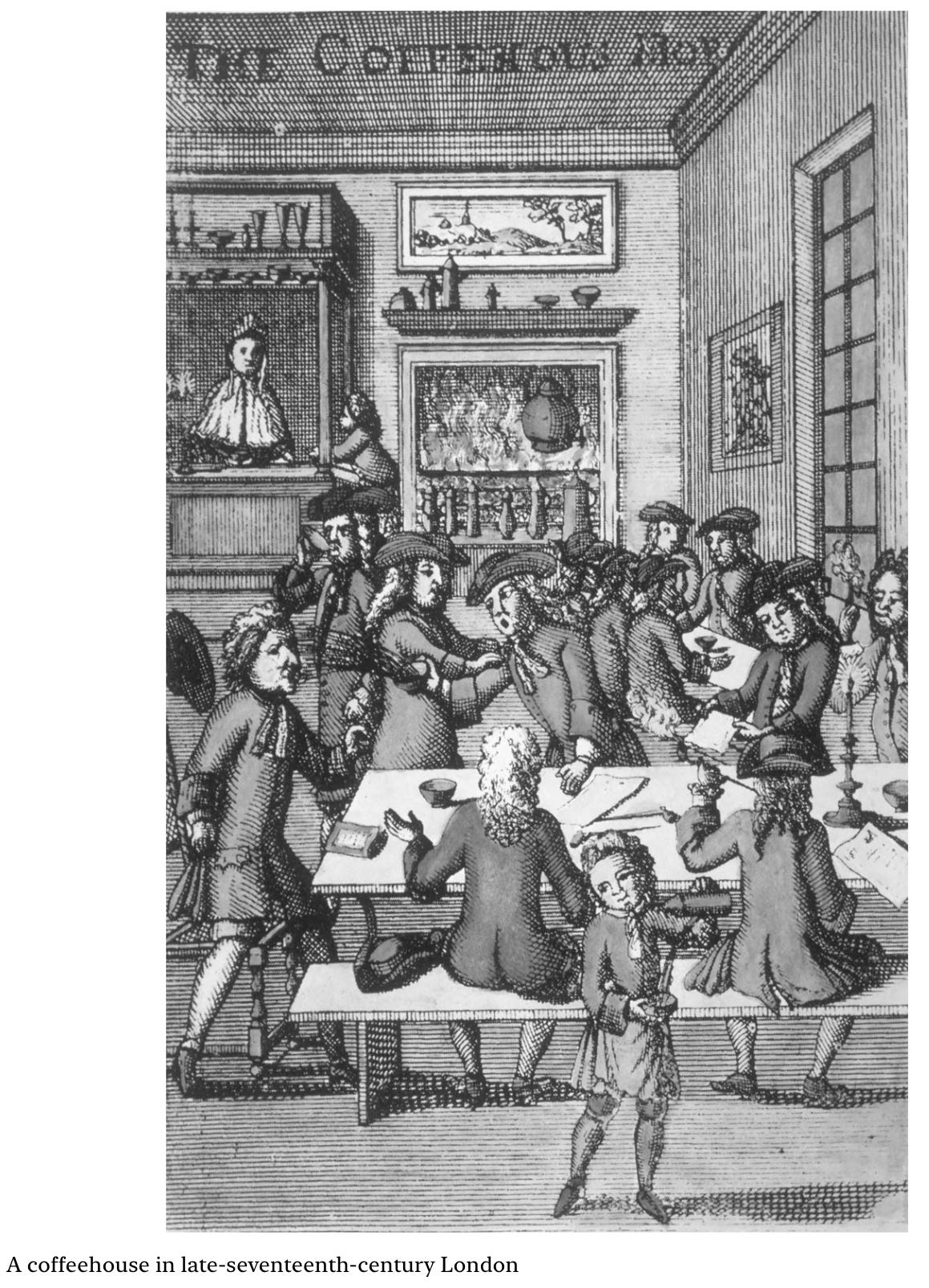

Coffeehouses opened in Britain in the 1650s and in Amsterdam and The Hague during the 1660s. As coffee moved west, it took the Arab notion of the coffeehouse as a more respectable, intellectual, and above all nonalcoholic alternative to the tavern along with it—and more than a whiff of controversy.

“Kofy” houses became fixtures of social, political, and commercial life in London in the 17th century. These coffeehouses tended to be “male only” stomping grounds. In short, “[t]he Arab drink had conquered Europe.” Ethiopians might vehemently disagree with the “Arab drink” designation.

Initially, the Europeans were at the import-export whims of the Arabs who (understandably) did everything to protect their coffee monopoly. The Dutch, “who displaced the Portuguese as the dominant European nation in the East Indies during the seventeenth century,” broke this monopoly by stealing “cuttings from Arab coffee trees, which were taken to Amsterdam and successfully cultivated in greenhouses.” The Dutch East India Company established coffee plantations in Batavia in Java (now Indonesia), and the Dutch were now in control of the coffee market despite the recognition that their coffee could not compete with Arab coffee as far as taste goes (cheaper, but not as tasty). You’ll note from my What is Rum Article – Part B that I mention the Dutch x Batavia because they also had a hand in developing Batavia Arrack, a sugarcane spirit that is a close cousin to rum (see, rum will always get mentioned!).

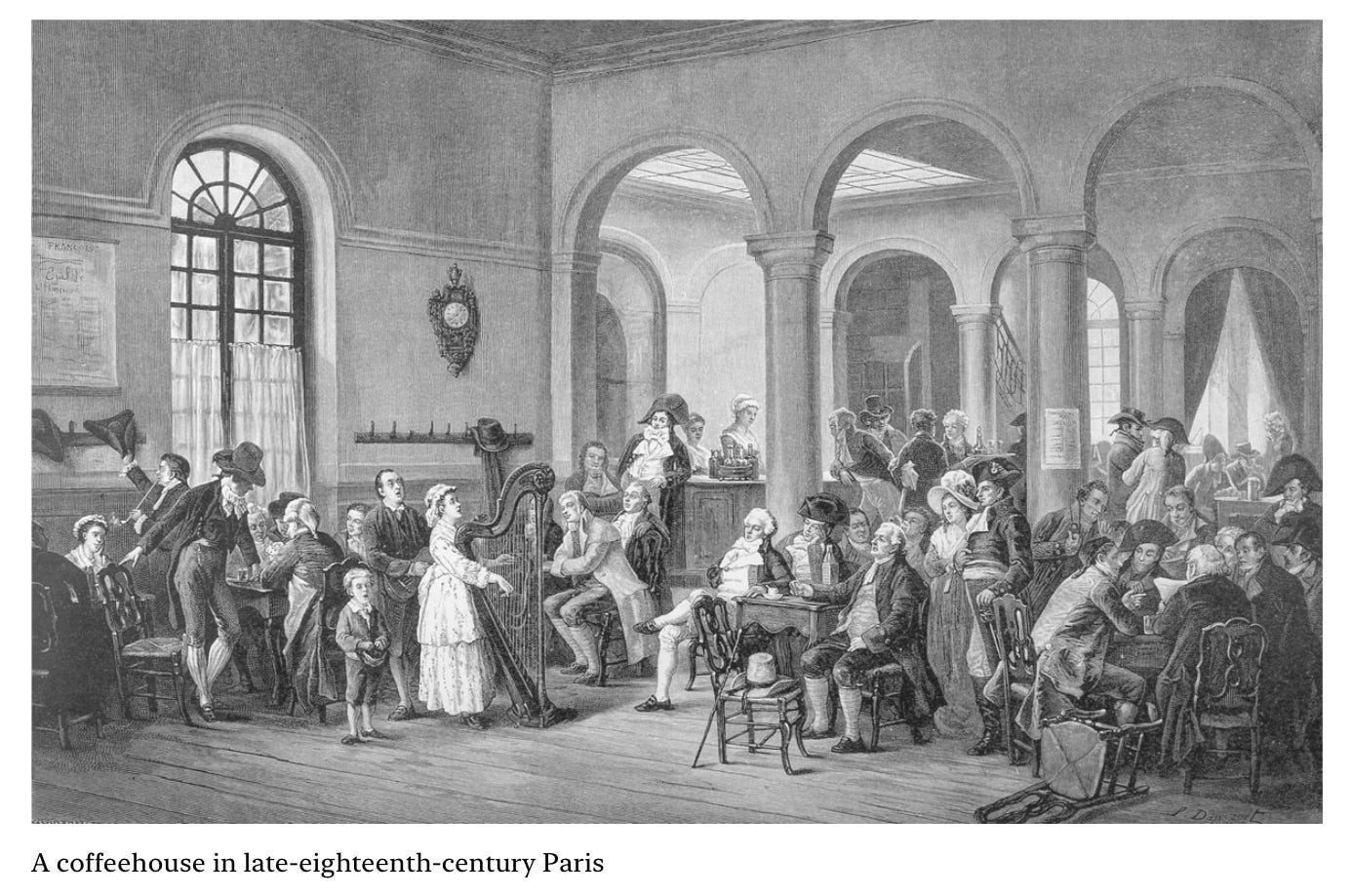

Next came the French, who, inspired by the Dutch, realized they could grow coffee in similar-ish climates in their colonies (West Indies). Consequently, the French brought coffee to Martinique and other islands. “Coffee exports to France began in 1730, and production so exceeded domestic demand that the French began shipping the excess coffee from Marseilles to the Levant.” Unlike the English, French coffeehouses were a male and female domain. On brand. However, like the English, coffeehouses became a place of discourse, intellectualism, and prestige.

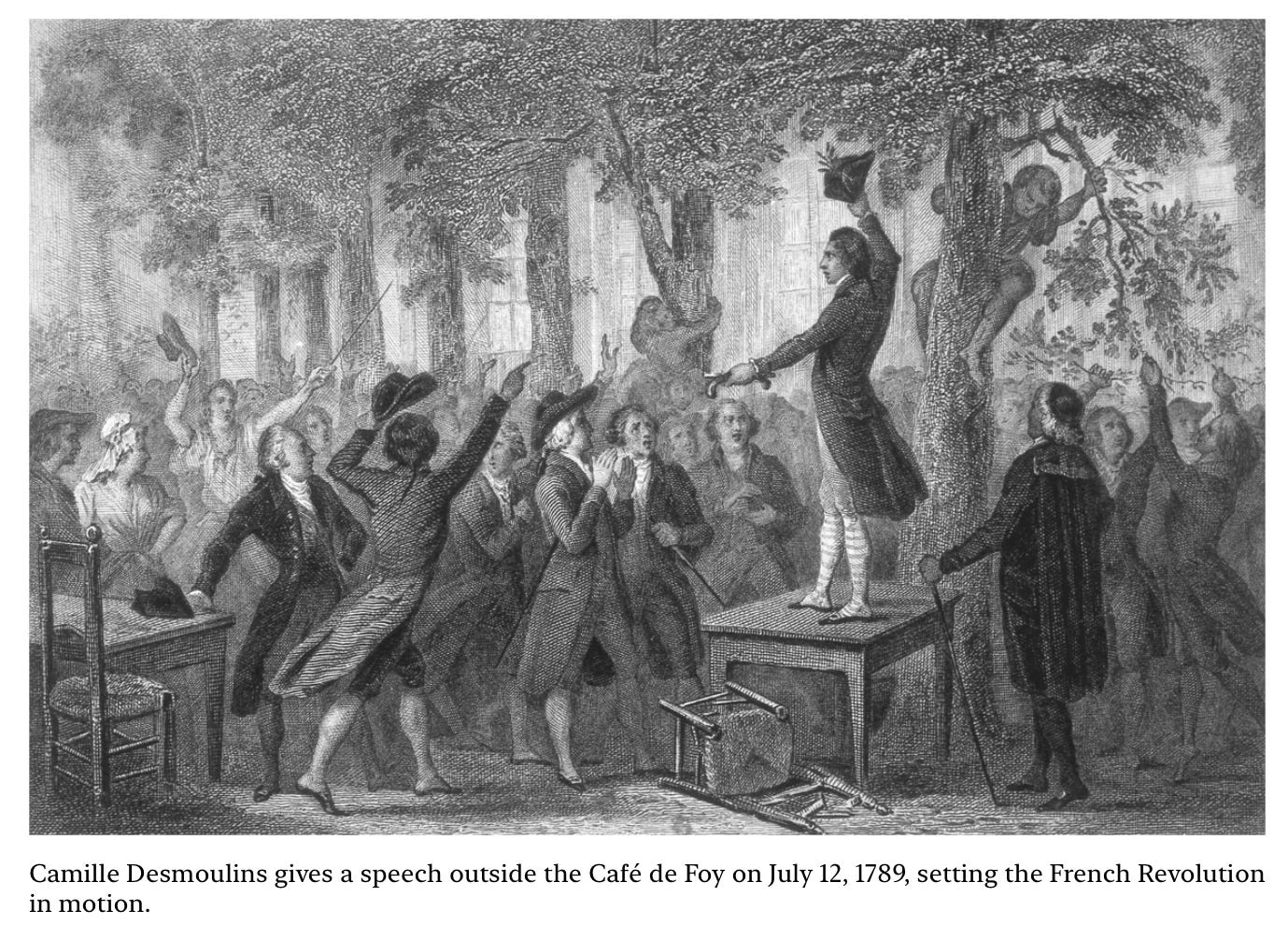

Maybe too intellectual for the likes of those in power. “Coffeehouses were centers of self-education, literary and philosophical speculation, commercial innovation, and, in some cases, political fermentation.” Coffeehouses served as a nucleus for news and gossip; French ruler(s) would’ve said that people were becoming a little too Enlightened. A significant difference between English coffeehouses and their French counterparts is that politics could not be openly discussed in the latter (locked in the Bastille). It is seemingly possible that coffeehouses in France served as breeding grounds for the popular French Revolution and the many more to come.

My personal close out on the coffee section.

I love it. Anytime I visit a part of the world that is a “coffee country,” I try to get to the primary coffee region and tour a family farm. The last time I did this was in Costa Rica. I am currently writing this while in Jamaica, home to the revered Blue Mountain Coffee. Funny enough, when I was in Costa Rica, the coffee farmer leading the tour said that his favorite coffee in the world is Columbian and Jamaican. Trust me, Blue Mountain Coffee is a delight.

I drink the black liquid in its raw form every morning. If not for coffee, would I have read this book?!. And to this, Standage would say –

Coffee remains the drink over which people meet to discuss, develop, and exchange ideas and information, just as it was hundreds of years ago. From neighborhood coffee mornings to academic conferences to business meetings, it is still the drink that facilitates collaboration and cooperation without the risk of the loss of self-control associated with alcohol…coffeehouses have once more become ad hoc offices and meeting rooms for businesspeople and mobile workers. Instead of providing tables of pamphlets and newsletters, such establishments are now expected to facilitate the caffeine-fueled exchange of information in a different way, by providing free Wi-Fi.

Tea, the OG Asian beverage.

If you taste tea from certain parts of Asia, you will understand they are light years ahead in the quality department. That supermarket tea does not hold water (pun intended) to those homegrown plants.

Better to be deprived of food for three days than of tea for one. — Chinese proverb

And when the British got their hands on it, they went loosey-goosey.

Thank God for tea! What would the world do without tea? How did it exist? —Sydney Smith, British writer (1771–1845)

And for the “empire on which the sun never sets” (i.e., how vast their time zone colonialism extended), getting their hands on tea, once they got that first sip, was mission numero uno. Despite losing certain North American colonies – American Revolution – the British were determined to continue their eastward expansion (India onwards). At the same time, Britain's Industrial Revolution was peaking (late 1700s into the early 1800s).

Linking these imperial and industrial expansions was a new drink—new to Europeans, at least—that became associated with the English and remains so to this day. Tea provided the basis for the widening of European trade with the East. Profits from its trade helped to fund the “advance into India of the British East India Company, the commercial organization that became Britain’s de facto colonial government in the East. Having started as a luxury drink, tea trickled down to become the beverage of the working man, the fuel for the workers who operated the new machine-powered factories. If the sun never set on the British Empire, it was perpetually teatime, somewhere at least.

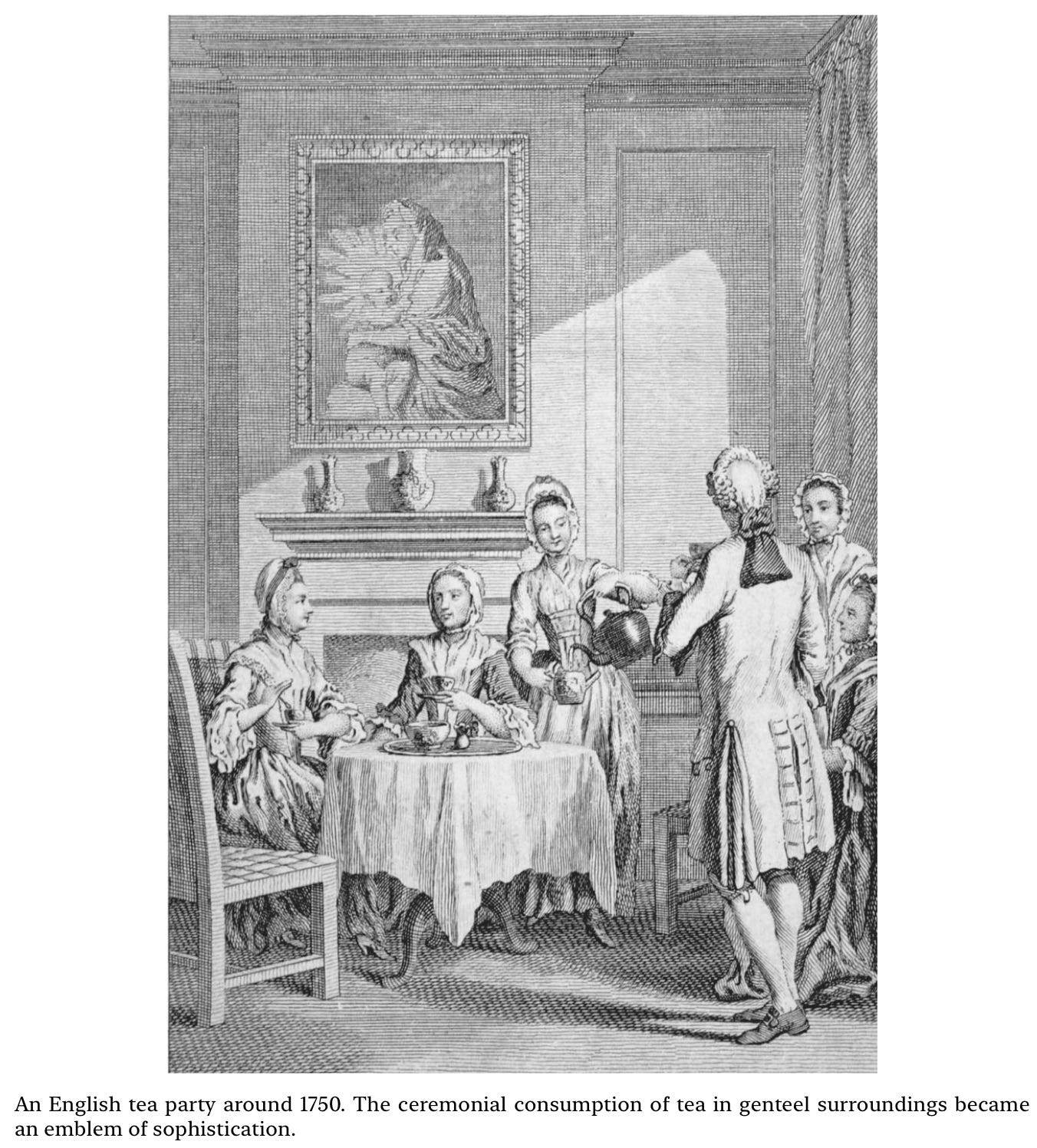

Some things snowball, over time, into culture and identity because, as I noted at the top of this section, tea has nothing to do with the British and everything to do with Asia. But that rhyme and reason – intellectually – would not have gelled in those days. In other words, one’s conquests equal one’s culture and inheritance. If the British conquered a tea country and then had full access to the best of teas, then it follows – by the logic of those times – that the tea is, therefore, British. The strength and profile of your empire was your culture. Tea drinking started as an upper-class ritual, which I think has continued in the form of activities such as afternoon high tea (example). The steep cost of transporting tea from China initially reinforced the reality that only those who could afford it would drink it. Not to mention that tea drinking became very popular among women in London because they were not allowed in coffeehouses.

…tea somehow became a central part of British culture. The drink that already lubricated China’s immense empire could then conquer vast new territories: Having won over the British, tea spread throughout the world and became the most widely consumed beverage on Earth after water. The story of tea is the story of imperialism, industrialization, and world domination, one cup at a time.

My immediate reaction is that the Chinese would be more inclined to affirm that “tea is the story of” tradition, family, culture, etc., and maybe all of those other things; Those other characterizations would be secondary.

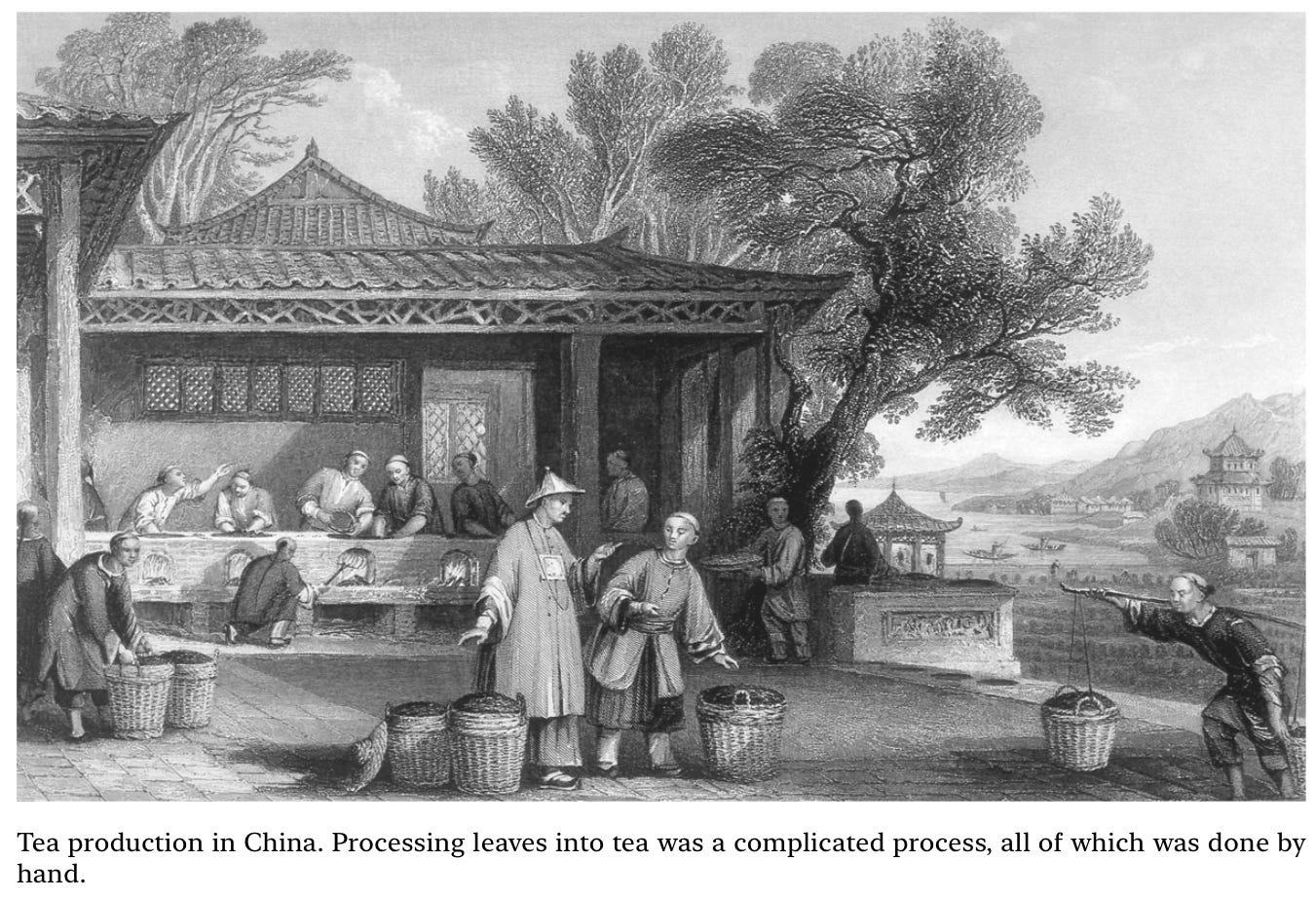

Chinese tradition suggests that the first cup of tea was brewed between 2737 and 2697 BCE by the (second) Emporer Shen Nung. Nung is also credited with the invention of agriculture and medicinal herbs. The legend goes that he was boiling some water to drink when a gust of wind blew some leaves from plants into the pot. He consumed the accidental mixture, and boom – tea. There’s also a legend that tea dates back to Buddhist monks in the sixth century BCE. Nonetheless, in the golden age of Chinese history, the Tang dynasty (618-907 CE), tea became the national beverage.

By 1718 tea was displacing silk as the mainstay of imports from China [into Britain]; by 1721 imports had reached five thousand tons a year.” At the height of the trade, tea represented 60 percent of the British East India Company’s activity. 10% of British government revenue came from the duties on the tea trade. With such strong influence over the British coffers, we know who called the shots back then. This is how it goes: As a result, control of the tea trade granted the company an enormous degree of political influence and enabled it to have laws passed in its favor.

The Dutch, the original capitalistic head honcho and trading behemoth, was all that stood in the British’s way of total control of the tea trade (eastern trade, broadly). So, the Britsh did what was true to their form at the time — take it: “A series of wars ended in 1784 with a Dutch defeat, and the rival Dutch East India Company was dissolved in 1795, granting its British counterpart almost total control of the global tea trade.”

Back to the Industrial Revolution and its fervent need for labor. Standage suggests that tea was the lubricant/ration provided to workers as liquid sustenance. For kids, too, because this ain’t the age of child labor concerns. You have a little one that could generate income for the family? They were put to work: “Infants benefited too, since the antibacterial phenolics in tea pass easily into the breast milk of nursing mothers. This lowered infant mortality and provided a large labor pool just as the Industrial Revolution took hold.”

The Industrial Revolution minted new businesspeople, helped by the efforts of the British East India Company, especially in the services sector. Here is an example of original influencer marketing and the spark of consumerism (reminder that women and tea in Britain was not a happy accident; women’s attraction to the beverage was, in part, born out of exclusion from coffeehouses) –

Wedgwood also pioneered the use of celebrity endorsements to promote his products: When Queen Charlotte, the wife of George III, ordered “a complete [set] of tea things,” he secured her permission to sell similar items to the public under the name “Queen’s ware.” He took out newspaper advertisements and staged special invitation-only exhibitions of his tea services, such as the one he produced for Empress Catherine II of Russia. At the same time, the marketing of tea was also becoming more sophisticated; the names of Richard Twining (son of Thomas) and other tea merchants became well known. Twining put up a specially designed sign over the door of his shop in 1787 and labeled his tea with the same design, which is now thought to be the oldest commercial logo in continuous use in the world. The marketing of tea and tea paraphernalia laid the first foundations of consumerism.

If you’re thinking, ‘that tea brand that I usually see in the grocery store,’ yes. They’ve been around for centuries and are central to the British monopoly on the Eastern/tea trade in the 18th century.

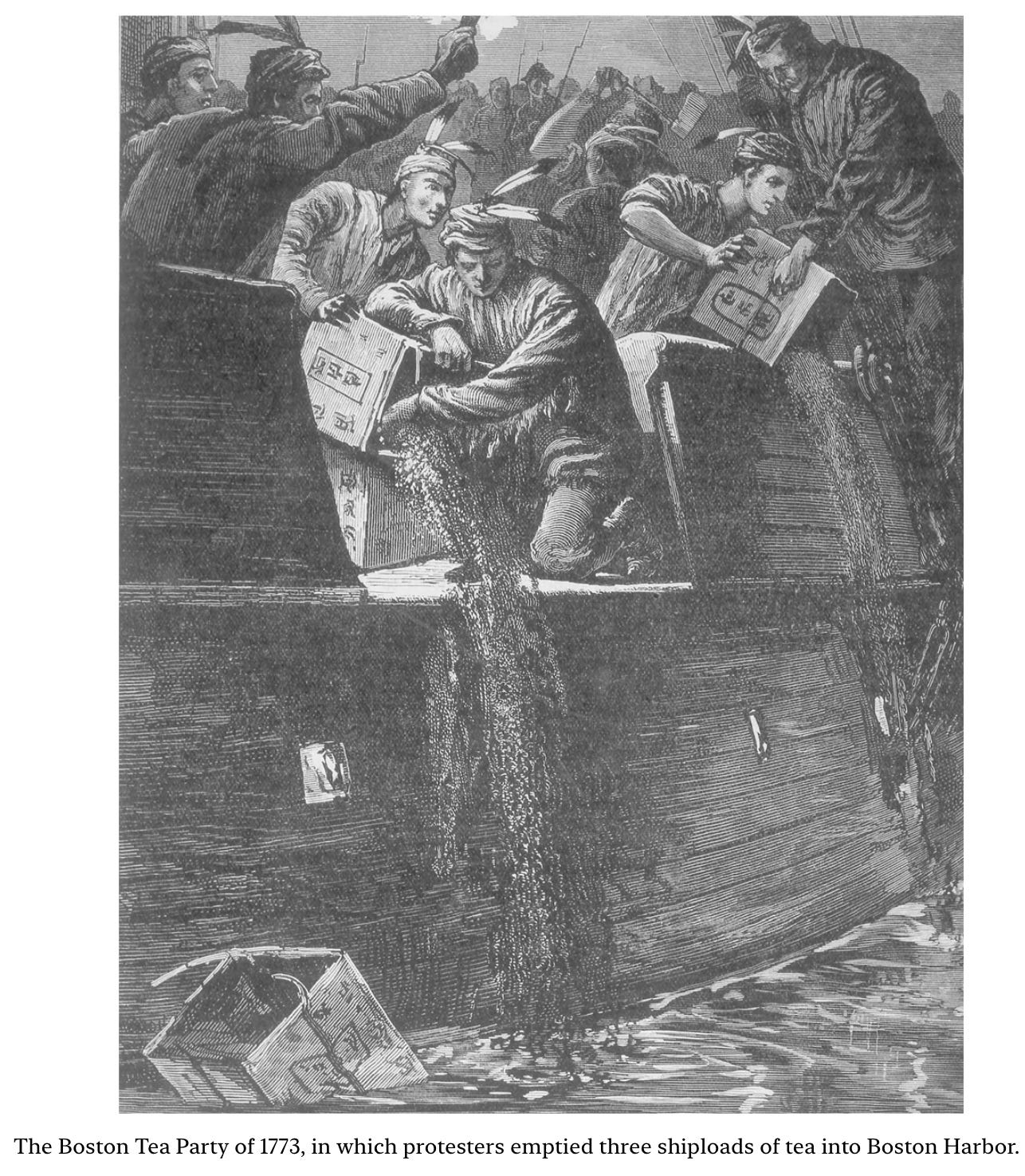

Like the sugar and molasses taxation fiasco (see Part 1/2 for reference), the American colonies opposed the duties levied on tea (you vaguely recall this story if you’re American) and tried to sidestep by importing tea from the Dutch instead. By now, you can see that these stories take on similar trends. British were still trying to pay off war debts from the Seven Years’ War. They imposed taxes – Tea Act of 1773 – on their colonies. Colonies say nay and start smuggling. “The American colonists, particularly those in New England, depended for their prosperity on being able to carry out unfettered trade without interference from London, whether buying molasses from the French West Indies with which to make rum, or dealing in smuggled tea from the Netherlands.”

December 1773, tea was dumped into the Boston Harbor in protest. British sought compensation for their losses, implemented more “coercive acts,” and eventually, the mantra of “No Taxation Without Representation” came to a head and spiraled into the American Revolution. Remember, rum got this started =)

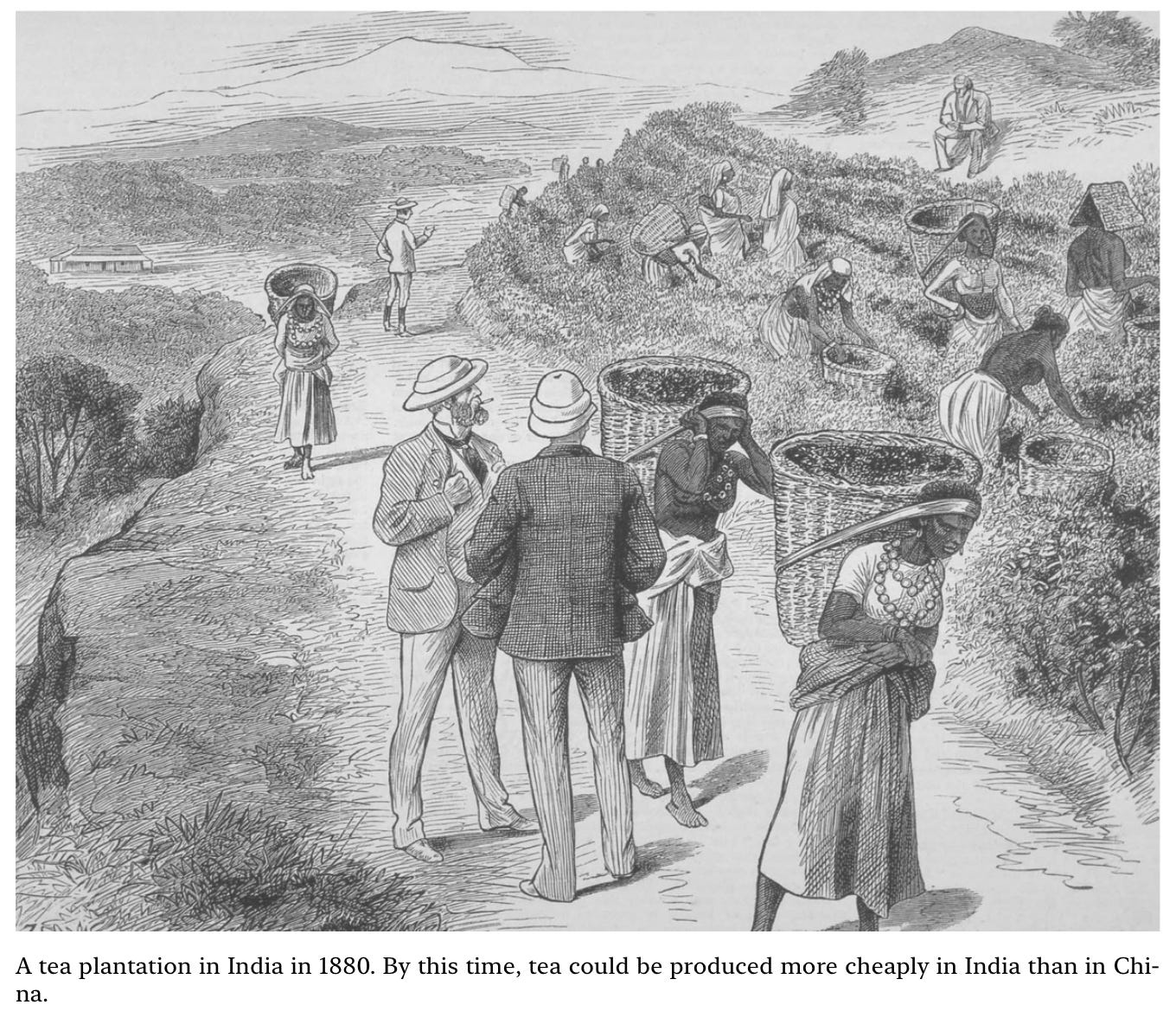

Fast forward – we know who the victors were – into the next century, the British East India Company shifted focus after losing its monopoly on the Chinese tea trade (the 1830s or so). They set their sites on India, whose economy the British played a role in decimating via the Industrial Revolution: cheaper, more “efficient” cloth making (England) vs. the artisans and hand-woven cloth of India. The weakened economy was then targeted by the British, who, using their knowledge of the tea trade/business, spurred by the British East India Company controlling and renting out lands to aspiring merchants (vs. doing the work themselves this time around), took over Indian tea plantations one by one. London merchants even created an enterprise called “Assam Company” to encourage “entrepreneurship” in the Indian tea cultivation and trade business. Note: Assam is a state in Northwestern India that is still well known for its tea farms. I think the British East India Company wanted to avoid another PR disaster – American Revolution – so they let others in on the business.

By the 1860s, helped along by industrial methods, tea manufacturing was in full force in India –

The tea plants were arranged in regimented lines; the workers were housed in rows of huts and required to work, eat, and sleep according to a rigid timetable. Picking the tea could not (and still cannot) be automated, but starting in the 1870s its processing could be. A succession of increasingly elaborate machines automated the rolling, drying, sorting, and packing of tea. Industrialization reduced costs dramatically: In 1872 the production cost of a pound of tea was roughly the same in India and China. By 1913 the cost of production in India had fallen by three-quarters. Meanwhile, railways and steamships reduced the cost of transporting the tea to Britain. The Chinese export producers were doomed.

Today, China (#1) and India (#2) are the largest tea producers globally. However, the lasting impact of British colonialism, vis-à-vis tea, can be seen and felt in those formerly under their rule. I would add “Jamaica” in the quote below because most Jamaicans are undoubtedly tea drinkers. One of the most revered products to come out of the island (Blue Mountain Coffee) is largely ignored (consumption-wise) by its population. The Japanese are the largest importers and consumers of Blue Mountain Coffee. Call me Japanese then because I drink ALL OF IT!

In the global ranking of tea consumption per capita, Britain’s imperial influence is still clearly visible in the consumption patterns of its former colonies. Britain, Ireland, New Zealand, and South Africa are four of the top twelve tea-consuming countries; many of the others are Middle Eastern nations, where tea, like coffee, has benefited from the Muslim prohibition of alcoholic drinks. The United States, France, and Italy are much farther down the list, each consuming around a tenth of the amount of tea per head that is drunk in Britain or Ireland, and favoring coffee instead.

My personal close out on the tea section.

The best I’ve ever had was in Thailand. I cannot wait to make my way across more of Asia to drink some good tea. A few places – India, Indonesia, Philippines – would allow me to double dip (rum). I think people who don’t like tea, like anything else, just haven’t had the high-quality stuff. I always keep a box of tea nearby. Age and maturity make me lean toward buying, steeping, and brewing loose tea. The beverage held me down when I did a year of no coffee drinking, which will never happen again. Did the same with alcohol (1 year abstention), and that also will never happen again.

Coca-Cola, a historical proxy for identifying “American culture”

I’m sure you have two questions:

Did the author really end the book with Coca-Cola, of all the drinks he could’ve chosen?

Was cocaine in Coca-Cola back in the day?

The answer to both of those questions is yes. More on #2 later.

The mass marketing of consumer goods feels – today – as American as hot dogs. It’s just what we do. It’s just who we are. There is an abundance of goods out there right now, which has seemingly sent people into a bit of a consumer spiral. Choice overload, meaning-seeking vs. pure consuming, etc. Let’s start with some background to help break down America <> Coca-Cola <> 1900s.

By the start of the twentieth century, America had surpassed Britain to become the largest economy in the world. It’s worth noting that – today – China is #2, India is #5, and the UK is #6. Empires rise and fall. Article for another day. Back to 18th century to 19th century America: raw materials abundant (big country); specialized machinery and differentiated Industrial Revolution (separating manufacturing from assembly); Much less tension in regional and class preferences (unlike European countries); Ease of mass marketing a product and selling it all across the country vs. worrying about regional distinctions; Burgeoning railway system further connecting the relatively homogenous country; “Soon even the British were importing American industrial machinery, a sure sign that industrial leadership had passed from one country to the other.”

My fellow Americans, when a European person is shocked at one of our fellow citizens not having a passport, you tell them – we’re still richer than you, boy! I’m kidding. These are all silly arguments that usually ignore the nuances of time, history, geography and circumstances. We still got more bread than you! Back to Coca-Cola, my bad.

Market trumps individual effort more than not. So, the release of Coca-Cola into an industrial/consumer/railway-d up America was bound to have more success than being released into a different market environment. Joseph Priestly of Leeds (Britain) is recorded as the first to produce carbonated soda. Could soda be traced back further, and is the Priestly attribution just the first documentation of carbonated soda production? Feels plausible. Standage was going to find a way to let us know the British started it. Well played.

Benjamin Silliman, “the first professor of chemistry at Yale University,” went to Europe in 1805 and was in awe of the soda water being sold by Schweppe and Paul. These European brands stand the test of time, sheesh. Yes, the Ginger Ale people! Ben returned to the States and started producing/selling soda water in New Haven. This seemed to set the tone for soda makers who sprouted thereafter. And now…finally…here we go with Coca-Cola.

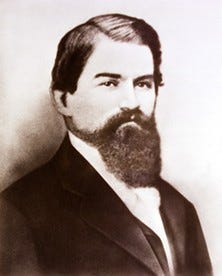

The story of Coca-Cola starts with John Pemberton, an Atlanta pharmacist, trying to invent a remedy for headaches in May 1886. Before the formalization, professionalization, and reverence that has become part and parcel of modern medicine, especially in the U.S., many medical professionals were seen as quacks who cooked up unreliable concoctions (e.g., paw paw pills) unabated. The media asked no questions; this is all pre-FDA, etc. Exhibit A –

There was nothing to stop manufacturers of such medicines from making outrageous claims about their effectiveness. The Elixir of Life sold by a Dr. Kidd, for example, claimed to cure “every known ailment.… The lame have thrown away crutches and walked after two or three trials of the remedy.… Rheumatism, neuralgia, stomach, heart, liver, kidney, blood and skin diseases disappear as by magic.” The newspapers that printed such advertisements did not ask any questions. They welcomed the advertising revenues, which enabled the newspaper industry to expand enormously; by the end of the nineteenth century patent medicines accounted for more newspaper advertising than any other product.

Pemberton started making progress because of the coca plant, otherwise known as “the divine plant of the Incas.” Small doses of the alkaloid drug released from chewing the plant sharpens the mind and reduces appetite (like caffeine). To show you how bad medicine was in the 19th century: “Cocaine was isolated from coca leaves in 1855, and it then became the subject of much interest among Western scientists and doctors, who thought it might help to cure opium addicts by providing an alternative.”

Pemberton followed those “recent studies” closely and incorporated the ingredient into his patents, specifically his “French Wine Coca.” However, on July 1, 1886, Atlanta and Fulton County prohibited the sale of alcohol for two years as the temperance movement gained ground. Pemberton needed to cook up a sober beverage asap: “He went back to his elaborate home laboratory and started work on a “temperance drink” containing coca and kola, with the bitterness of the two principal ingredients masked using sugar. This would be no ordinary patent medicine, though; he intended it to be dispensed as a medicinal soda-water flavoring.”

Voila, Coca-Cola. Still had the cocaine in it. Friends, this was not a secret by any means –

The first advertisement for the new drink, which appeared in the Atlanta Journal on May 29, 1886, was short and to the point: “Coca-Cola. Delicious! Refreshing! Exhilarating! Invigorating! The new and popular soda fountain drink containing the properties of the wonderful Coca plant and the famous Cola nut.” The new drink had been launched just in time for Atlanta’s experiment with Prohibition. It was nonalcoholic, and it appealed as both a soda-water flavoring and a patent medicine.

Initially, Pemberton sold only the syrup-based end product to pharmacists and soda fountain owners vs. a bottled product. That was later introduced/franchised, which resulted in the explosion of the business. “Bottled Coca-Cola opened up entirely new markets, because it could now be sold anywhere—at grocery stores and at sporting events, for example—not just at soda fountains.” The distinctive “Coca-Cola bottle shape” glass was introduced in 1916.

And here’s where things take a turn, from a cultural standpoint. Coca-Cola overtook coffee as the premier social/staple drink (in the U.S.) because it was deemed suitable for a) drinking at any point in the day and b) children/people of all ages. The drink – again, back to market/market-timing – flourished during Prohibition and the Great Depression, largely due to its “brilliant publicist, Archie Lee,” who was instrumental in Coca-Cola’s placement, marketing, and brand messaging.

By the end of the 1930s Coca-Cola was stronger than ever. Unquestionably a national institution, accounting for nearly half of all sparkling soft-drink sales in the United States, Coca-Cola was a mass-produced, mass-marketed product, consumed by rich and poor alike. In 1938 the veteran journalist William Allen White, a respected social commentator, declared it to be “a sublimated essence of all that America stands for, a decent thing honestly made, universally distributed, conscientiously improved with the years.” Coca-Cola had taken over the United States; now it was ready to take over the world, going wherever American influence extended.

A sumblimated essence of all that America stands for.

World War II, Coca-Cola went where the troops went and remained an emblem and reminder of home for those off in distant lands: “…Robert Woodruff, president of the Coca-Cola Company, issued an order that “every man in uniform gets a bottle of Coca-Cola for five cents, wherever he is, and whatever it costs the company.” I have no doubt that an unintended, or maybe even intended, consequence of having the presence of Coca-Cola all over the world with military personnel resulted in the citizens of other nations seeing Coca-Cola and this being imprinted in their brains as something desirable. “The Coca-Cola Company rapidly expanded its overseas operations during the late 1940s, so that by 1950 a third of its profits came from outside the United States.”

The opposite is also true. Communist sympathizers in France started using the term “Coca-Colonization” because they did not want the company’s bottling plants in France. “It would, they suggested, harm the domestic wine and mineral-water industries; they even tried to have Coca-Cola outlawed by asserting that the beverage was poisonous.” If you read any of my rum articles, you know that I think the French are particularly particular about defending their home grown beverages/industries. There’s the Pepsi vs. Coca-Cola saga, but I don’t think that’s worth covering here. We’ll end with Standage’s direct words –

…Coca-Cola was unquestionably the drink of the twentieth century and all that went with it: the rise of America, the victory of capitalism over communism, and the rise of globalization. In the twenty-first century, however, the once-sparkling mixture has lost much of its appeal.

My personal close out on the Coca-Cola section.

Not much of a soda drinker. Coffee, water, and spirits are my triangle. Ginger-Ale once in a blue, maybe, but that’s about it.

Before we close, this Standage “last call” is worth the (re)mention.

When you next raise some beer, wine, spirits, coffee, tea, or Coca-Cola to your lips, think about how it reached you across space and time, and remember that it contains more than mere alcohol or caffeine. There is history, too, amid its swirling depths.

Thanks, Standage.

A final word, for real.

There’s a show rendition of 6 Glasses on Fox. Anyone tuned in? I need to watch!

Disclaimer: If some of the review feels wanting, apologies. Please fill in where I may have left out (assuming you’ve read 6 Glasses); more hands/pens benefit readers.

And remember,

in all that you do, please, don’t ever stop reading.