Tom Standage — A History of the World in 6 Glasses (Part 1/2)

This first half is the no sobriety intro – beer, wine, and spirits

You will hear me say this often – I LOVE when journalists write books.

British, though? Teasing. Jokes aside, his occupational stripes scream British: he is the Deputy Editor of The Economist. He also went to Oxford, where he studied engineering and computer science (both is crazy). Standage put that STEM brain to use by power of the pen intersecting historical (analogy) in science, technology, and business (e.g., he wrote a book titled A Brief History of Motion). The man also likes “to play the drums, play video games and drink wine. But not all at the same time, obviously.”

His daughter, Ella, wrote a bio for him in 2006 (at age 6) that I think will tickle the brovaries of even the coarsest men among us: “My daddys name is tom. he tells me storys. he likse beer coffee and rum. he has bron hair and blue eyes. he has a nose that looks funny. he is 36 years old. he is great! he has big ears. he works in the Economist. he ritse books. he isent very good at gardening. he dose smelly farts. I love him.” (source)

I also LOVE like rum, Tom. But my farts dosen’t smelly, at least not to me.

How did I arrive at this book?

Circa 2022 or 2023, a business school classmate (wine enthusiast) and I scheduled a coffee catch-up and inevitably talked about books. If Standage ever reads that last sentence, it will likely make him chuckle (wine enthusiast recommending a book at a coffee shop, coffee being consumed at or near a university campus, etc.). My friends, this will make a lot more sense to you when you get to the coffee and tea section. Promise.

Where was I? A friend recommended the book to me. And like many great books that I’ve read, trusted sources/readers are a reliable way to discover your next best read. A History of the World in 6 Glasses was my second book this year after Nexus, which felt topical given the ‘here’s how this all came together’ theme across both pieces of work.

When you next raise some beer, wine, spirits, coffee, tea, or Coca-Cola to your lips, think about how it reached you across space and time, and remember that it contains more than mere alcohol or caffeine. There is history, too, amid its swirling depths.

A herculean effort in condensing the history of certain beverages.

Beer, wine, spirits (rum, dammit), coffee, tea, and Coca-Cola (in that order) to connect the dots of human indulgence above and beyond H20. Standage’s writing has undoubtedly left him open to beverage-enthusiast criticisms, both for the drinks included in the book and those who felt their drink(s) were unjustifiably left out. I know that authors, and certainly journalists, clearly understand that their work will be scrutinized. The author doesn’t pretend to think that these 6 beverages – 3 caffeinated, 3 alcohol – tell the complete story of humankind. Only that “each one was the defining drink during a pivotal historical period, from antiquity to the present day.” But still, discussing (anything) about wine, for instance, may invite a specific type of sharp eyes and tongue. When reading anything rooted in history, I try to take the glass half-full approach partly because it feels more practical.

In other words, expecting a historical text to cover every account and variation of events/developments can be unreasonable. That would take a life of editing in perpetuity because the shoelace of information becomes undone anytime there is a discovery. Any piece of historical text, therefore, covers “what was” and then becomes a fixed analysis until someone else picks up where they left off. We should still expect accuracy, thorough research, truthfulness, etc., for all historical accounts, no doubt. That said, I was left craving details and analysis on ancestral drinking habits across ancient (West/West Central) Africa and Asia. But there are other texts for those accounts, and that’s okay.

There is no history of mankind, there are only many histories of all kinds of aspects of human life. — Karl Popper, philosopher of science (1902–24)

Drinks have had a closer connection to the flow of history than is generally acknowledged, and a greater influence on its course. Understanding the ramifications of who drank what, and why, and where they got it from, requires the traversal of many disparate and otherwise unrelated fields: the histories of agriculture, philosophy, religion, medicine, technology, and commerce. The six beverages highlighted in this book demonstrate the complex interplay of different civilizations and the interconnectedness of world cultures. They survive in our homes today as living reminders of bygone eras, fluid testaments to the forces that shaped the modern world. Uncover their origins, and you may never look at your favorite drink in quite the same way again.

Beer, let’s disrupt whatever you thought you knew about the beverage’s origins.

The event that set humankind on the path toward modernity was the adoption of farming, beginning with the domestication of cereal grains, which first took place in the Near East around ten thousand years ago and was accompanied by the appearance of a rudimentary form of beer. The first civilizations arose around five thousand years later in Mesopotamia and Egypt, two parallel cultures founded on a surplus of cereal grains produced by organized agriculture on a massive scale. This freed a small fraction of the population from the need to work in the fields and made possible the emergence of specialist priests, administrators, scribes, and craftsmen. Not only did beer nourish the inhabitants of the first cities and the authors of the first written documents, but their wages and rations were paid in bread and beer, as cereal grains were the basis of the economy.

First, Mesopotamia is modern-day Iraq (plus).

Second, Ock is responsible for beer. This is hilarious.

Third, about 12,000 years ago, hunter-gatherers said – “no more nomad living, let’s plant food and drink this mashed-up barley and wheat liquid [beer].” (not an actual quote)

This would’ve been even funnier if he was near the beer. Anywho, source: Tik Tok x @magicatitagain

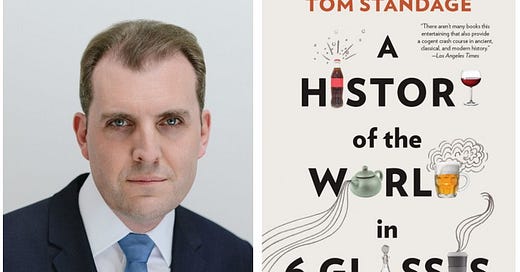

Jokes aside, this domestication of cereal grain was widespread along a vast area of territories called the Fertile Crescent (“…modern-day Egypt, up the Mediterranean coast to the southeast corner of Turkey, and then down again to the border between Iraq and Iran.”). Following the Ice Age, which I assume provided more abundant water resources/irrigation capabilities along the Fertile Crescent (contributing to it being referred to as such), lots of wild wheat and barley flourished. In addition to the cereal grain, the environment became ideal for sheep, goats, cattle, and pigs, providing a nutritious set-up-shop arena for a previously itinerant group.

The no-longer-itinerants made beer like so: Moistened their cereal grains, converting the starch into malt —> this maltose sugar became popular at a time when other sources of sugar were not widespread —> malting techniques were developed (soaking and drying the grain) —> left this sitting out in a Middle Eastern/North African sun, fermentation was bound to take place (wild yeasts turning sugar into alcohol) —> Voila, beer.

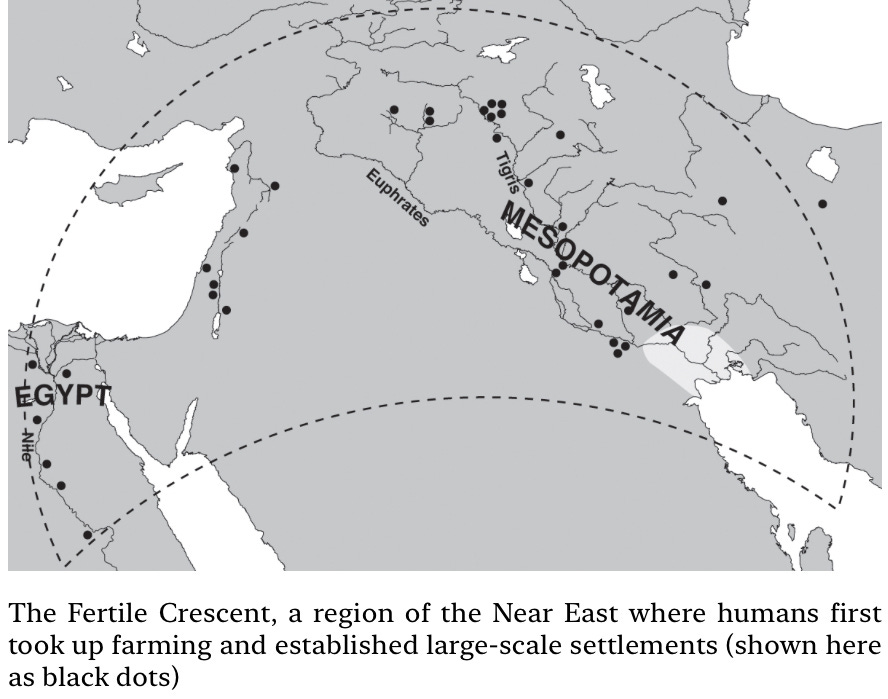

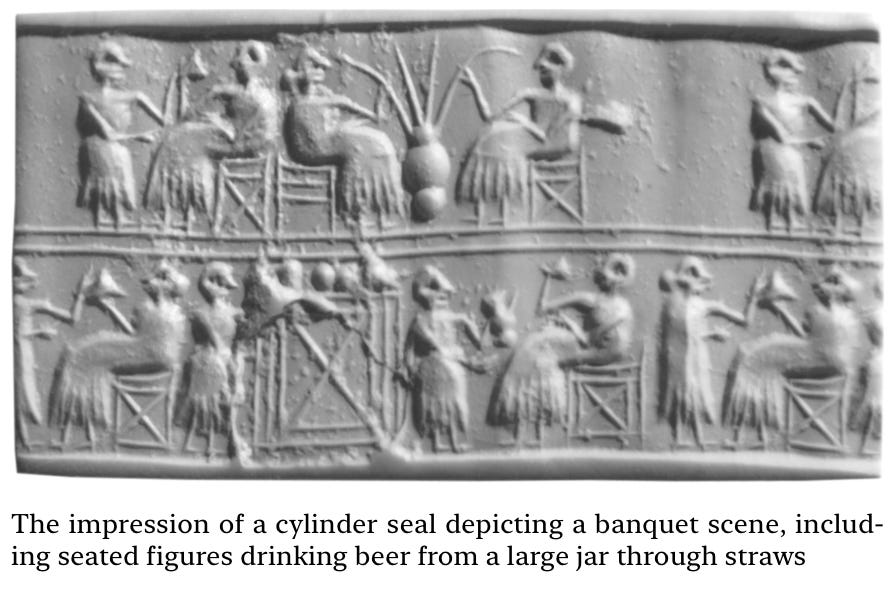

Sharing your beer from the same vessel to emphasize that you and your fellow no-longer-itinerant were drinking the same liquid was deeply symbolic at the time and maybe even practical (no need to get another vessel when modern-day hygiene and bacterial concerns weren’t a thing). But this beer sharing became “a universal symbol of hospitality and friendship. It signals that the person offering the drink can be trusted, by demonstrating that it is not poisoned or otherwise unsuitable for consumption.” The people who enjoy ordering those tall, fruity cocktails with multiple straws are like – finally, I have the historical context to express why I do what I do!

And when drinking alcohol in a social setting, the clinking of glasses symbolically reunites the glasses into a single vessel of shared liquid. These are traditions with very ancient origins.

For many at this time, beer drinking was also considered a more practical and healthier alternative to other liquid consumption –

…beer helped to make up for the decline in food quality as people took up farming, provided a safe form of liquid nourishment [away from contaminated water], and gave groups of beer-drinking farmers a comparative nutritional advantage over non-beer drinkers.

And then, as has often happened throughout history, the chess pieces move: beer is bougie. Across both Egypt and Mesopotamia (we’re still talking BCE), the excess grain surplus began funding public works (pyramids, canals, and such). Grain and its by-product(s), bread & beer, became logical forms of currency and exchange. And the Mesopotamians regarded hunter-gatherers, the people they just were not too long ago, as primitive – “look at them over there, they gotta keep walking and looking for food and booze.” (not an actual quote, obviously)

The Mesopotamians regarded the consumption of bread and beer as one of the things that distinguished them from savages and made them fully human. Interestingly, this belief seems to echo beer’s association with a settled, orderly lifestyle, rather than the haphazard existence of hunter-gatherers in prehistoric times.

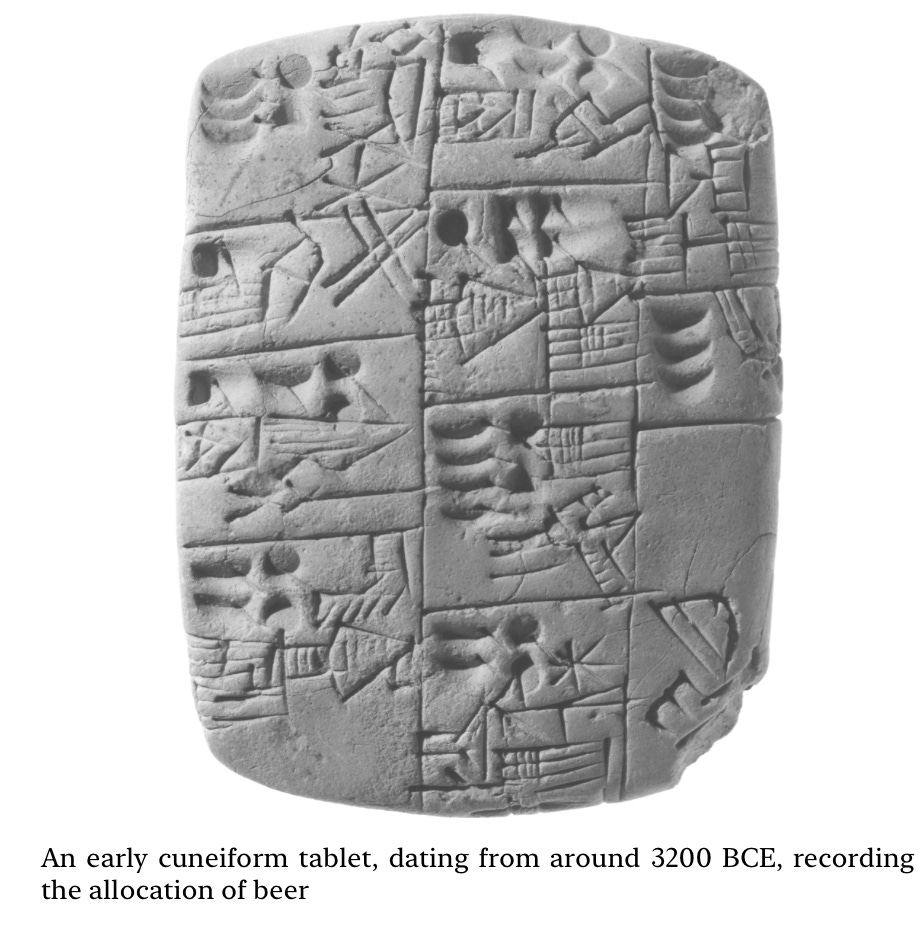

When you have time on your hands and beer to drink, I suppose you start noting these things down. Wage lists and tax receipts. Taxes in the form of grain, to be explicit, Benjamin Franklins weren’t available yet, or Pounds (my bad, Standage). Distributions and collections. They had to know where all this bread & beer was going.

If you or I see two people drinking beer with a straw from the same vessel (today), we’d be concerned or nosy at the beer minimum (couldn’t resist). But this was in vogue at one point, likely seen as a status symbol activity of the elite/those with leisure time.

My personal close out on the beer section.

I used to be 100% convinced that people did not like the taste of beer. I viewed beer as a drink that people only consumed to be social, fit in, or some variation of I-don’t-actually-want-to-drink-this-but-I'm-going-to. Super ignorant since I only developed that point of view when I went to college, misremembering the avid Red Stripe, Heineken, and Guinness drinkers (Jamaicans) who had a hand in bringing me up along the way. Also, a very US-centric point of view because (from what I can tell) a South African woman will give a Mexican man a run for his money with beer consumption (random example).

Then, in business school, a few good guys (pictured below) and one lad took me out to a beer tasting somewhere on the Upper East Side in NYC (I think). Before this, if I were to reach for a beer, it would always be a Guinness my macho man beer, or likely what I got used to from the “this will strengthen your back,” “peanut punch” chattings I sporadically ingested. Ultimately, I realized that I gravitated to stouts (dark beers) because I love things that pack depth and richness of flavor. Everything else in beer land felt light and odd-tasting. But that’s purely because of exposure. We did the tasting, and it was great. I recall liking every beer I tried (across the different styles).

Will I willingly order a beer now when I’m out? Unlikely. I have to be feeling adventurous. Probably just won’t drink if I don’t see any rum alcoholic beverages that I like.

Wine, the “I’m just feeling for a glass of” beverage.

Its origin is lost in prehistory. We can only be assured that it is old as hell: “…archaeological evidence suggests that wine started to be produced during the Neolithic period, between 9000 and 4000 BCE, in the Zagros Mountains in the region that roughly corresponds to modern Armenia and northern Iran.”

Ock again like –

Because it was produced in the mountains, likely better soil/climate for grape growing, wine was difficult to obtain (labor and price). Econ 101 (BCE): when supply is limited and the product is difficult to get, it’s bougie.

Previously, wine had only been available in Mesopotamia in very small quantities, since it had to be imported from the mountainous, wine-growing lands to the east. The cost of transporting wine down from the mountains to the plains made it at least ten times more expensive than beer, so it was regarded as an exotic foreign drink in Mesopotamian culture. Accordingly, only the elite could afford to drink it, and its main use was religious; its scarcity and high price made it worthy for consumption by the gods, when it was available. Most people never tasted it at all.

Today, there are over 10,000 wine variety grapes, though a dominant handful (Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot, Pinot Noir, Sauvignon Blanc, etc.) occupy the mindshare and shelf space across the globe. Lots of supply now, but wine can still be very pricey. What hasn’t changed from the ancient days to now is the perception of wine as the drink of distinguishment and a refined palette. Why? Because the Ancient Greeks and Romans said – we’re not like the beer drinkers, we drink wine. A slight amnesia on the part of the Ancients given that much of their civilization received (directly/indirectly) inspiration and precedent from the Ancient Mesopotamians and Egyptians (e.g., writing and empire structures).

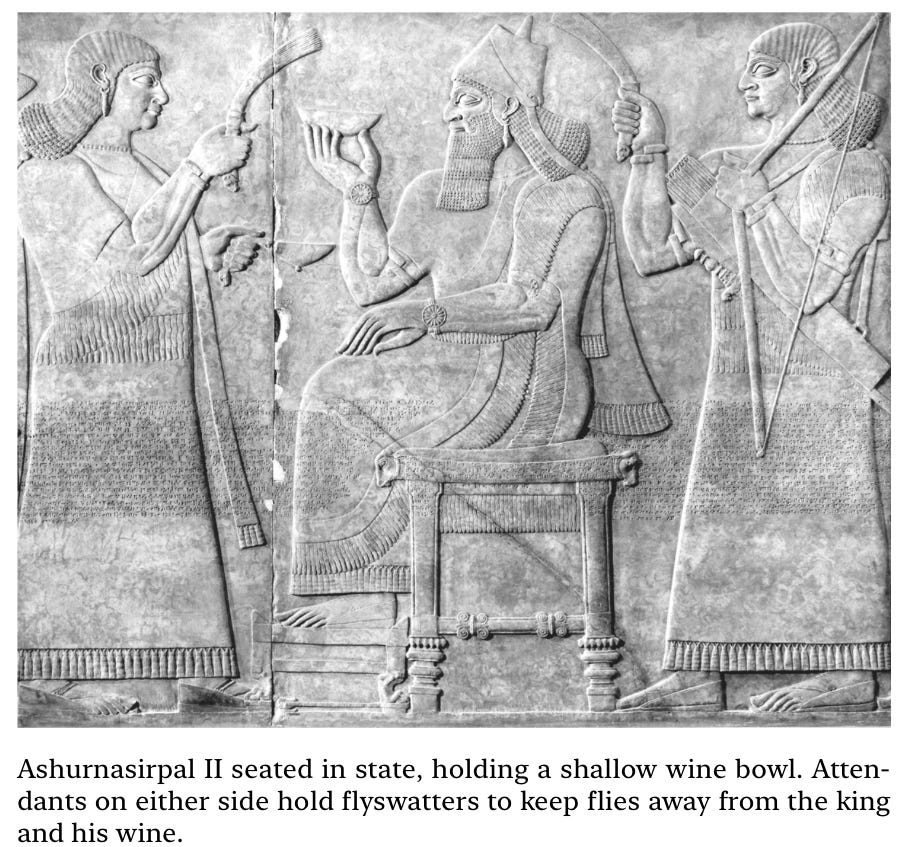

Under the King pictured above and his subsequent family members (Assyrian Empire), the nascent wine industry hit a turning point: more widely produced/consumed, cemented as an elite beverage (initially), and traded on the high seas. As more lands were conquered, fewer borders needed to be crossed, and wine production subsequently expanded in those newly conquered regions (Syria, Israel, Lebanon, Egypt). But remember, because of labor and availability, wine was still considered an elite beverage, notwithstanding the Barefoot substitutes –

…a substitute drink became popular instead: date-palm wine, an alcoholic drink made from fermented date syrup. Date palms were widely cultivated in southern Mesopotamia, so the resulting “wine” was just a little more expensive than beer. During the first millennium BCE, even the beer-loving Mesopotamians turned their backs on beer, which was dethroned as the most cultured and civilized of drinks, and the age of wine began.

Ancient Greece is oft-credited as the cradle of Western civilization/thought (philosophy, politics, science, law, etc.). Institutionalized competition abounded across those domains, as well as sports and commerce. The Greeks referred to those of the east as Barbaroi (Barbarians). Those to the east were of the aforementioned empires containing Mesopotamia, Syria, Egypt, and “Asia Minor” (modern-day Turkey). The Greeks touting their appreciation for wine vis-à-vis the “Barbarians” love for beer snowballed into their psyche that wine is sophistication. This thought process has, for some, held up in modern times.

Gradually, grain farming was overtaken by the cultivation of grapevines and olives, and wine production switched from subsistence to industrial farming. Rather than being consumed by the farmer and his dependents, wine was produced specifically as a commercial product. And no wonder; a farmer could earn up to twenty times as much from cultivating vines on his land as he could from growing grain. Wine became one of Greece’s main exports and was traded by sea for other commodities. In Attica, the switch from grain production to viticulture was so dramatic that grain had to be imported in order to maintain an adequate supply. Wine was wealth; by the sixth century BCE, the property-owning classes in Athens were categorized according to their vineyard holdings: The lowest class had less than seven acres, and the next three classes up owned around ten, fifteen, and twenty-five acres, respectively.

Wine displaced beer to become the most civilized and sophisticated of drinks—a status it has maintained ever since, thanks to its association with the intellectual achievements of Ancient Greece.

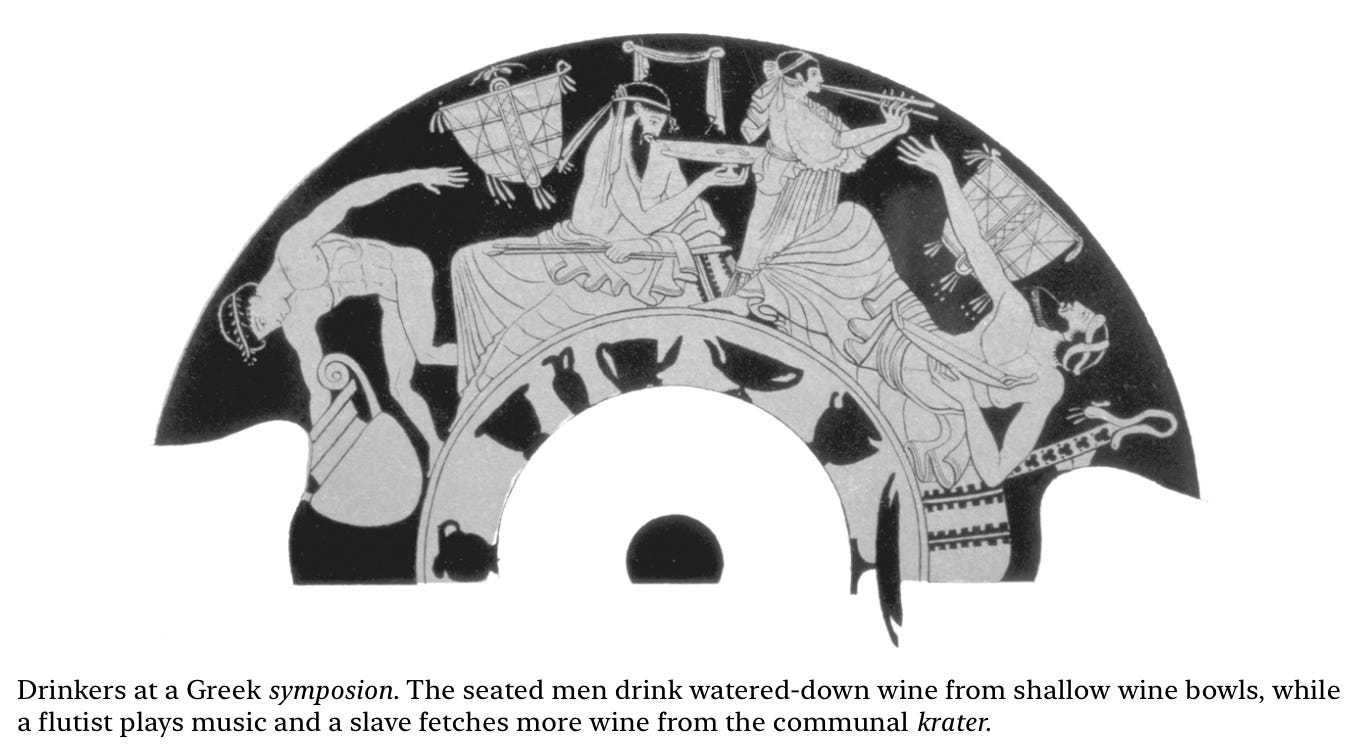

To frustrate the wine drinkers reading this piece, guess what? The Greeks were mixing the beverage with other liquids. My assumption is that it was a primitive form of wine, too tart for the palette. Water was used to dilute the wine, which served as the primary drink at symposiums of mostly men of status in Greek society. Enslaved labor was critical to the cultivation of wine, which provided philosophers and the like with the leisure to gather and…chat.

At heart, the symposion was dedicated to the pursuit of pleasure, whether of the intellectual, social, or sexual variety. It was also an outlet, a way of dealing with unruly passions of all kinds. It encapsulated the best and worst elements of the culture that spawned it. The mixture of water and wine consumed in the symposion provided fertile metaphorical ground for Greek philosophers, who likened it to the mixture of the good and bad in human nature, both within an individual and in society at large.

I’m no genius, but I can read between the “sexual variety” and “unruly passions of all kinds” lines. “I’m about to head down to the dome, you know, chat about what it means to be or not to be, you know…”

My reading of Standage’s work suggests that the Greeks introduced the French and Italians to wine via export/trade around the fifth century BCE. The Spanish and Portuguese introduction is a little less clear. What is known is that by the middle of the 6th century BCE, the Romans (Central Italy) replaced the Greeks as the most dominant force in the Mediterranean basin. Standage notes that the new leadership represented “a strange sort of victory, since the Romans, like many other European peoples, liked to show how sophisticated they were by appropriating aspects of Greek culture.” Their gods, their myths, their architecture, their constitution, their language (“Educated Romans studied Greek literature and could speak the language.”), and indeed – the wine.

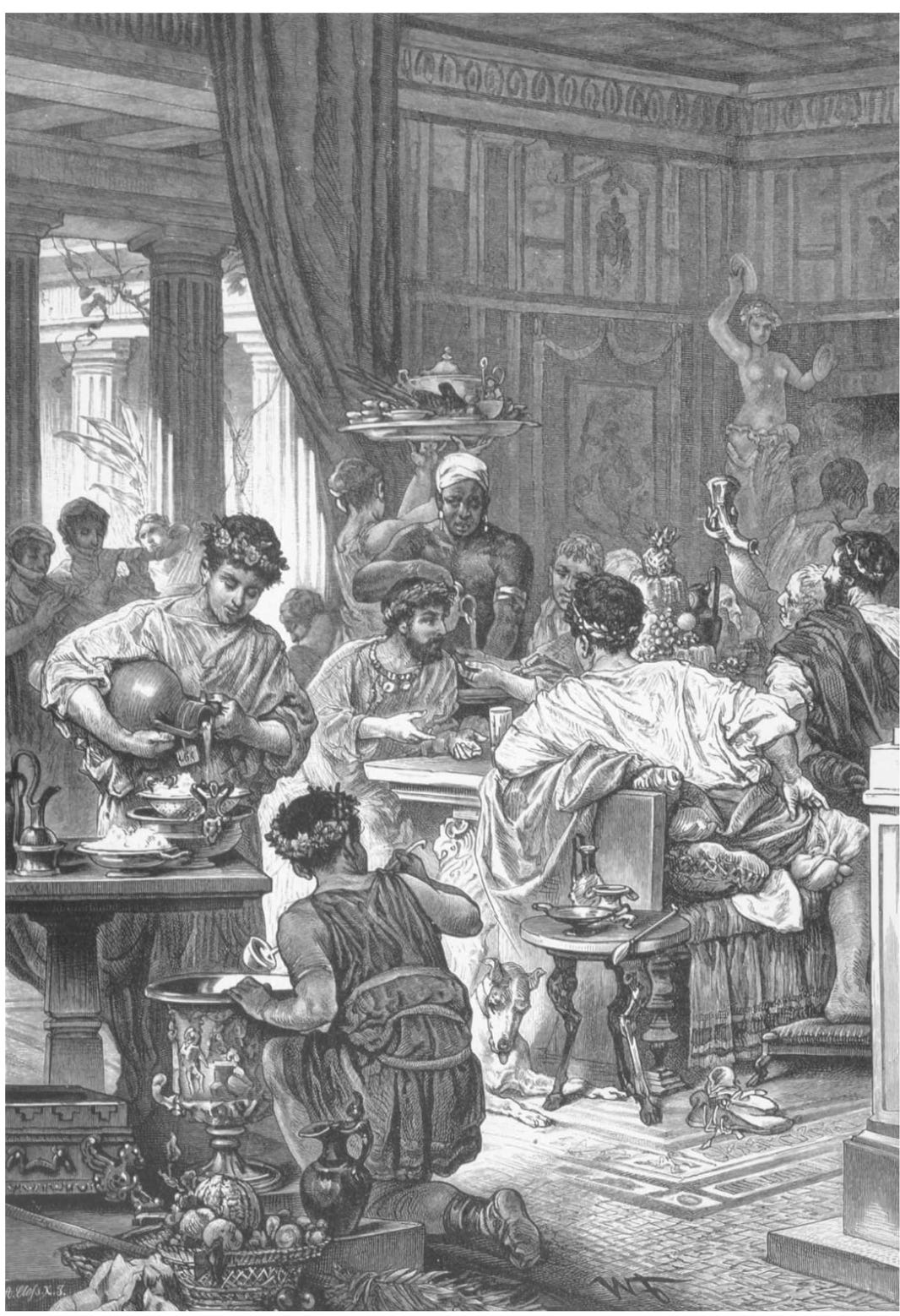

The most prestigious crop to grow for Romans was the vine. Reportedly, Roman soldiers would be rewarded with tracts of farmland after successful war campaigns so that they could cultivate the vine. The VI(ne) Bill. That was a horrible dad-ish joke, but I’m keeping it. Wine represented victory and civilization as the Romans “enjoyed lavish feasts and drinking parties in Greek-style villas.”

The Italian peninsula became the world’s foremost wine-producing region around 146 BCE, just as Rome became the leading Mediterranean power with the fall of Carthage in northern Africa and the sack of the Greek city of Corinth.

Just as they assimilated and then distributed so many other aspects of Greek culture, the Romans embraced Greece’s finest wines and wine-making techniques. Vines were transplanted from Greek islands, enabling Chian wine, for example, to be grown in Italy. Winemakers began to make imitations of the most popular Greek wines, notably the seawater-flavored wine of Cos, so that Coan became a style rather than a mark of origin. Leading winemakers headed from Greece to Italy, the new center of the trade. By 70 CE, the Roman writer Pliny the Elder estimated that there were eighty wines of note in the Roman world, two-thirds of which were grown in Italy.

Servants and enslaved people became necessary to wine production since the Romans (and traditional styles of cultivation) could not keep up with demand. Large estates began to spring up, and all of the Romans’ energy and resources shifted to prioritize grape/wine cultivation. They supplemented their other needs with importation (e.g., African grain) from those they conquered.

Romans used wine to differentiate between the classes, specifically by one’s quality of wine. Example: “The finest wine of all, by universal assent, was Falernian, an Italian wine grown in the region of Campania. Its name became a byword for luxury and is still remembered today.” Posca and Lora wines were relegated to the lower classes. However, everyone embraced the “When conquered by in Rome” thing and drank wine of some sort.

And then the Ock of all Ocks said, let’s put an end to all this, please and thank you –

By the time of Muhammad’s death in 632 CE, Islam had become the dominant faith in most of Arabia. A century later, his adherents had conquered all of Persia, Mesopotamia, Palestine and Syria, Egypt and the rest of the northern African coast, and most of Spain. Muslims’ duties include frequent prayer, almsgiving, and abstention from alcoholic drinks.

Tradition has it that Muhammad’s proscription of alcohol followed a fight between two of his disciples during a drinking party. When the prophet sought divine guidance about how to prevent such incidents, Allah’s reply was uncompromising: “Wine and games of chance … are abominations devised by Satan. Avoid them, so that you may prosper.

The ban on alcohol was, however, enforced more rigorously in some places than in others. Wine was celebrated in the work of Abu Nouwas and other Arab poets, and production continued in Spain and Portugal, for example, even though it was technically illegal. And the fact that Muhammad himself was said to have enjoyed lightly fermented date wine led some Spanish Muslims to argue that his objection was not so much to wine itself as to overindulgence.

Historical accounts, always intriguing.

It seems that wine’s association with being civilized and sophisticated is primarily tied to the range of intellectual/societal accomplishments during the time of Ancient Greece and Rome (i.e., the cradle(s) of Western civilization). This is a profound case of ‘the stories we tell ourselves’ having an enduring impact –

Greek and Roman attitudes toward wine, themselves founded on earlier Near Eastern traditions, have survived in other ways, too, and have spread around the world. Wherever alcohol is drunk, wine is regarded as the most civilized and cultured of drinks. In those countries, wine, not beer, is served at state banquets and political summits, an illustration of wine’s enduring association with status, power, and wealth.

We can agree that wine – today – has an aura of distinction and class embedded in how people perceive the beverage. There are wine-people who even make it part of their persona to actively shy away from appearing to be a snobby wine person, the anti-wine (toeing the line here). If wine is at dinner, cutlery is probably placed in a certain way, the environment may be composed of certain people, etc. You may even have someone responsible for selecting the wine, a ritualistic ordeal if I've ever seen one (not mad at it at all, to be fair). And to this, Standage would say: “It is a scene that a time-traveling Roman would recognize at once.”

My personal close out on the wine section.

The stuff is good, let’s be honest. Food-wine pairings done well are always magical experiences. One of the best I ever had was in Lisbon, Portugal. I won’t pretend to be well-versed, but, like my Guinness preference, bold and deep flavors are my jam. So, when ordering wine, I usually default to a) red, b) full-body, c) dry. Always open to trying new flavors (white wine, if I must), but that’s my uninformed go-to.

Spirits, THE CHAMP IS HERE.

I'll TRY to curb my bias for rum when discussing this section. TRY!

This is how the Spirits section came through – to me – after the wine bit.

If you don’t know this scene/movie, if you didn’t immediately hear the “HOWEVERRRRRR” playing in your head, shoot me a note, my young friend, we’ll talk this through #welosingrecipes

Ock does it again with the inventions –

At the close of the first millennium CE, the greatest and most cultured city in western Europe was not Rome, Paris, or London. It was Córdoba, the capital of Arab Andalusia, in what is now southern Spain…They developed the astrolabe, algebra, and the modern numeral system, pioneered the use of herbs as anesthetics, and devised new navigational techniques based on the magnetic compass (an introduction from China), trigonometry, and nautical maps. Among their many achievements, they also refined and popularized a technique that gave rise to a new range of drinks: distillation.

We can back up a bit (“fourth millennium BCE”) to see that northern Mesopotamian Ocks had simple distillation equipment that was likely used for making perfumes. And if you’ve ever stepped into a room full of Arabs, you know that smelling good is mundane for them. My mind wanders back to my Bahrain and Egypt trips. To date, one of my favorite Middle Eastern perfume houses was recommended to me by a Saudi business school classmate who affectionately said that there’s no such thing as a correct number of sprays. Respect. Whoa, off track – back to spirits. It is incredibly funny that Ock created the hardware to make consumable alcohol and said “nah, we don’t even drink that.”

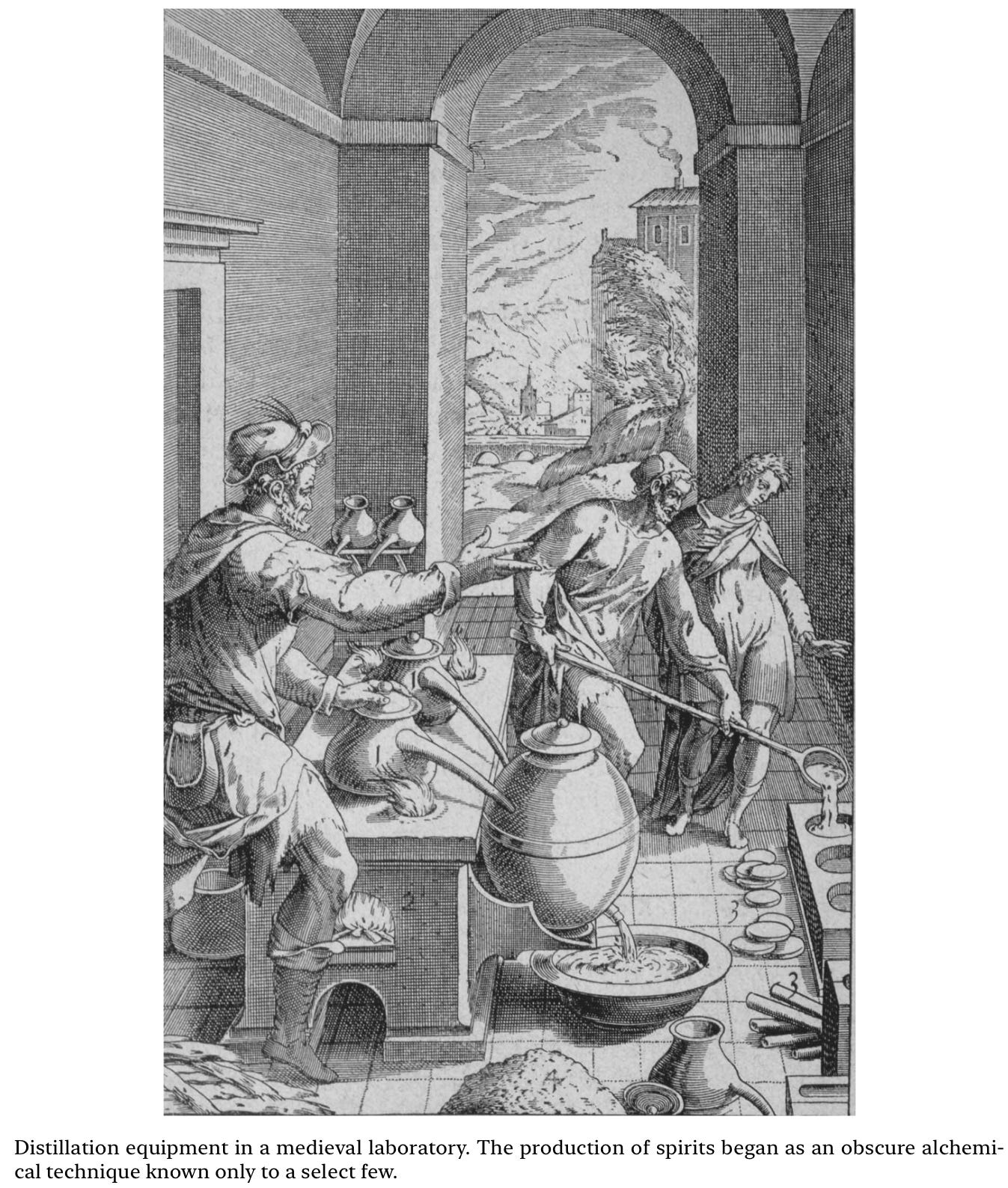

But it was only later, starting in the Arab world, that distillation was routinely applied to wine, notably by the eighth-century Arab scholar Jabir ibn Hayyan, who is remembered as one of the fathers of chemistry. He devised an improved form of distillation apparatus, or still, with which he and other Arab alchemists distilled wine and other substances for use in their experiments.

And then it took off with the Western Europeans –

The word alembic, which refers to a type of still, encapsulates this combination of ancient knowledge and Arab innovation. It is derived from the Arabic al-ambiq, descended in turn from the Greek word ambix, which refers to the specially shaped vase used in distillation. Similarly, the modern word alcohol illuminates the origins of distilled alcoholic drinks in the laboratories of Arab alchemists. It is descended from al-koh’l, the name given to the black powder of purified antimony, which was used as a cosmetic, to paint or stain the eyelids. The term was used more generally by alchemists to refer to other highly purified substances, including liquids, so that distilled wine later came to be known in English as “alcohol of wine.”

The distillation of wine and other beverages was mostly viewed by the Arabs as a form of medicine, not an everyday drink. During the age of imperialism, the Europeans took the shipmaking, navigation techniques & devices (e.g., compass), and mathematical inventions of the Arabs, combined them with Arab distillation techniques, and set in motion redefining the world as we know it today (trading goods, geographical conquests, human capture and trade for said goods, etc.). The Europeans also viewed alcohol as having deep medicinal qualities, likely inspired by the Arabs, but they took consuming it to another level. Even going so far as to call a specific type of alcoholic beverage/medicine Aqua vitae, or water of life.

But for most people, aqua vitae’s appeal came not from its supposed medicinal benefits but from its power to intoxicate people quickly and easily. Distilled drinks proved particularly popular in the cooler climes of northern Europe, where wine was scarce and expensive. By distilling beer, it was possible to make powerful alcholic drinks with local ingredients for the first time. The Gaelic for aqua vitae, uisge beatha, is the origin of the modern word whiskey.

You know if whiskey/beer is involved, the Irish are there! Although “cooler climates of Northern Europe” likely also refers to England. But, unbeknownst to many – the Portuguese got this “exploration” thing going before other European powers, then the Spanish, and on and on.

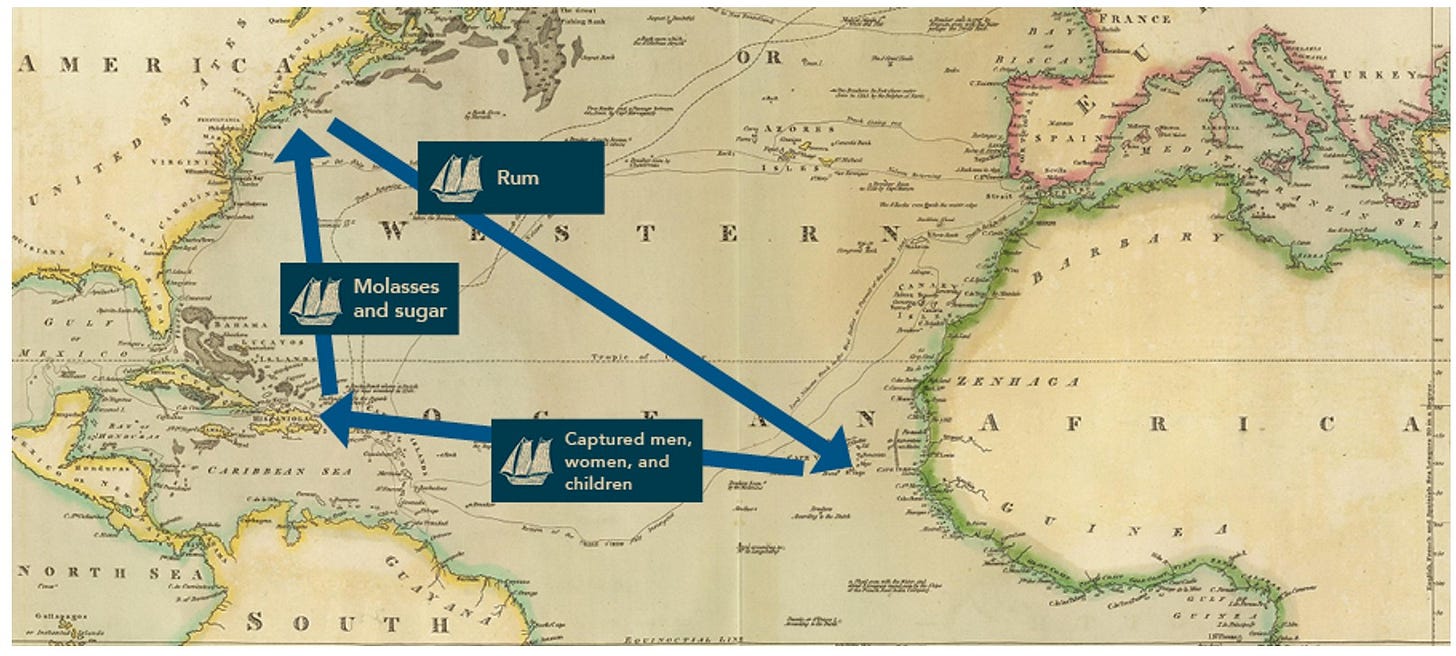

Standage titles the section on rum “The First Global Drink.” This is likely a nod to the transportation of sugarcane and knowledge from places like Madeira (Portuguese colonized) to Brazil. Then, from Brazil, settlers had an example of sugarcane —> spirit distillation. There will be a review on Frederick H Smith’s book, Caribbean Rum, where I’ll dive into this a bit more. The takeaway, for now, is that this interaction of sugarcane brought into the Americas, along with enslaved Africans and white indentured servants, resulted in the creation of predecessor cane spirits and, eventually, rum. I’ll leave you with an important analysis to close off the rum piece –

…when rum was first invented. Its immediate significance was as a currency, for it closed the triangle linking spirits, slaves, and sugar. Rum could be used to buy slaves, with which to produce sugar, the leftovers of which could be made into rum to buy more slaves, and so on and on. Jean Barbot, a French trader, observed on visiting the west coast of Africa in 1679 that he found “a great alteration: the French brandy, whereof I had always had a good quantity abroad, being much less demanded, by reason that a great quantity of spirits and rum had been bought on that coast.” By 1721 one English trader reported that rum had become the “chief barter” on the slave coast of Africa, even for gold. Rum also took over from brandy as the currency in which canoemen and guards were paid. Brandy helped to kick-start the transatlantic trade in sugar and slaves, but rum made it self-fueling and far more profitable…Rum was the liquid embodiment of both the triumph and the oppression of the first era of globalization.

Sorry, we have to keep talking about rum (read: I'm not sorry). My fellow Americans, the first colonists on our side of the pond – mainly New England and the East Coast – tried their hands at domestic beer and wine. But those grains and grapes were difficult to cultivate in colder climates; They didn't have the farming know-how in this New World. “They tried to make wine from local grapes instead, but the result was revolting. Eventually, the Virginia colonists decided to concentrate on the commercial cultivation of tobacco, and to import malted barley (from which to make beer) from Europe, along with wine and brandy.” This is about first half of the 1600s or so.

Everything changed in the second half of the seventeenth century, however, when rum became available… Rum quickly established itself as the North American colonists’ favorite drink. It alleviated hardship, provided a liquid form of central heating in the harsh winters, and conveniently reduced the colonists’ dependence on imports from Europe. Rum was generally drunk neat by the poor, and by the better off in the form of punch—a mixture of spirits, sugar, water, lemon juice, and spices served in an elaborately decorated bowl.

Let me hammer that ‘rum is American’ point home again –

From the late seventeenth century, rum formed the basis of a thriving industry, as New England merchants—primarily in Salem, Newport, Medford, and Boston—began to import raw molasses rather than rum and do the distilling themselves. The resulting rum was not thought to be as good as West Indies rum, but it was even cheaper, which was what mattered to most drinkers. Rum became the most profitable manufactured item produced in New England.

But it was the importation of raw molasses, largely from French (Haiti) and Spanish (Cuba) colonies that pissed off the British because the Brits would have preferred its North American colonies to import British-owned Caribbean molasses for rum production. What happens when you take money out of the British Empire's pocket? They tax you for that befuddled act of malarky (is how I imagine they would’ve described it back then).

The New England distillers’ use of French molasses added insult to injury. The British producers called for government intervention, and in 1733 a new law, known as the Molasses Act, was passed in London.

It was a case of supply and demand. In true ‘vee pwotect hour intuh-west’ fashion, the French had beaucoup molasses to supply from their “sugar-territories” because they prohibited rum production in those islands. They did not want rum competing with their continental wine, brandies, etc. Note: this does not mean that cane spirit production was completely curtailed, just moved underground (for now). So, there was not much the British could do. The molasses coming out of the ”sugar-territories” under the British Crown was in much lower supply (i.e., rum was produced freely in those territories and exported to Europe as well), so other Empires stepped in to fill the gap for New Englanders. Strict adherence to the Molasses Act would have crippled the New England economy and (most importantly) “deprived the North American colonists of their favorite drink.”

The Molasses Act was passed, not very enforced, still very much resented, but ultimately ignored.

At the same time, the number of distilleries making rum in Boston grew from eight in 1738 to sixty-three in 1750. Rum continued to flow, maintaining its position in all aspects of colonial life. It played an important role in election campaigns: When George Washington ran for election to Virginia’s local assembly, the House of Burgesses, in 1758, his campaign team handed out twenty-eight gallons of rum, fifty gallons of rum punch, thirty-four of wine, forty-six of beer, and two of cider—in a county with only 391 voters.

And then, war – French and Indian (1753 – 1764), or the Seven Years’ War; the British said if you don’t stop selling them molasses, we gotta fight! Not really. They fought over Ohio and Canada. But the French did have the Russians on their side. Do you see why context is important vs. just saying these statements out loud?

Where were we? Back to the drinks. Long and short of it: British won the war, but now they had war debts to repay. When you are the big man, you tax the little man. Voila, the Sugar Act of 1764, which effectively stepped up the vigilance/seriousness of the Molasses Act: “Colonial governors were required to enforce the laws strictly and arrest smugglers, and the Royal Navy was given the power to collect duties in American waters.” But the Americans said, we just helped you beat the French, and we’re not even represented in this distant parliament we’re paying taxes to. Naturally, the (soon-to-be war) cry of “no taxation without representation” became a popular slogan. Advocates of independence, known as the “Sons of Liberty,” began to mobilize public opinion in favor of a break with Britain.” Friendly reminder that the origin of this is molasses <> rum.

A series of Acts were passed – unrelated to rum, sort of – and the American Revolution was on its way. Even during the fighting, however, rum remained important throughout the cause and thereafter. I’ve totally lost the battle on not talking about rum too much. Whatever.

General Henry Knox, writing to George Washington in 1780 about the procurement of supplies from the northern states, emphasized the particular importance of rum. “Besides beef and Pork, bread & flour, Rum is too material an article, to be omitted,” he wrote. “No exertions ought to be spar’d to provide ample quantities of it.” The taxation of rum and molasses, which began the estrangement of Britain from its American colonies, had given rum a distinctly revolutionary flavor.

At this juncture, you’re probably wondering – where is the whiskey?! The war had disrupted the supply – trade, generally – of molasses to America. At the same time, the westward movement, expansion, and territory conquering post-American Revolution saw the desire for a cheaper distilled spirit (alternative) than sugarcane/rum. Many Americans switched to rum alternatives purely out of cost and practicality of cultivation factors, in addition to the Scot-Irish heritage influence of many westward settlers.

And while grains such as barley, wheat, rye, and corn were difficult to grow near the coast—hence the early colonists’ initial difficulties with making beer—they could be cultivated more easily inland. Rum, in contrast, was a maritime product, made in coastal towns from molasses imported by sea. Moving it inland was expensive. Whiskey could be made almost anywhere and did not depend on imported ingredients that could be taxed or blockaded.

I’ve pointed out in prior write-ups and will continue to emphasize going forward: when something becomes practical and profitable over a long duration of time, it often then gets molded into “heritage.” That’s just the way it is. No rhyme, just a whole lot of practical reasoning until it looks foolish to abandon. Unless another profitable thing comes across, of course.

By 1791 there were over five thousand pot stills in western Pennsylvania alone, one for every six people. Whiskey took on the duties that had previously been fulfilled by rum. It was a compact form of wealth: A packhorse could carry four bushels of grain but could carry twenty-four bushels once they had been distilled into whiskey. Whiskey was used as a rural currency, traded for other essentials such as salt, sugar, iron, powder, and shot. It was given to farmworkers, used in birth and death rituals, consumed whenever legal documents were signed, given to jurors in courthouses and to voters by campaigning politicians. Even clergymen were paid in whiskey.

And then America started to do what the British did. Who is going to pay for this war debt (American Revolution)? You boys making whiskey are! “In March 1791 a law was passed: From July 1, distillers could pay either an annual levy or an excise duty of at least seven cents on each gallon of liquor produced, depending on its strength.” Note: From my What is Rum (Part C) article, where I discussed alcohol ABV and taxes, this is where a lot of it – in America – stems from. What do people do when they don’t want to be taxed? They rebel (not anymore, back then). The Whiskey Rebellion (1791—1794) was led by the “whiskey boys” of…(creating suspense here)…Western Pennsylvania (not Kentucky). I know, I know. It seemed to be a fairly mild rebellion (deaths and destruction-wise), which ultimately failed, cementing the heavy hand of federal law.

Spirits section is thick, I know, we’re wrapping up now – promise.

A lot of the westward-moving (new) Americans, many of whom were Scot-Irish, and many of whom were fleeing the oppressive (taxation) regime of the British Empire in their own lands, flocked inward (Midwest), where they continued the Pennsylvania traditions of distilling whiskey, this time from both corn and rye. “The production of this new kind of whiskey was pioneered in Bourbon County, so that the drink became known as bourbon.” Corn was (is) a Native American indigenous crop, so I’m reasonably certain that the blueprint for growing it in a bountiful way was a learning hurdle that did not need to be scaled as steeply. Wheels are turning in my mind. I want to do a lot of reading on the history of Bourbon/American whiskey. For another time. I’ll close this section with a thought-provoking quote from the author.

Distilled drinks, alongside firearms and infectious diseases, helped to shape the modern world by helping the inhabitants of the Old World to establish themselves as rulers of the New World. Spirits played a role in the enslavement and displacement of millions of people, the establishment of new nations, and the subjugation of indigenous cultures. Today, spirits are no longer associated with slavery and exploitation. But other echoes of their uses in colonial times persist. Air passengers who throw a bottle of duty-free spirits into their hand luggage do so because it is a compact form of alcohol that is hardy enough to survive a long journey unspoiled. And in their desire to avoid excise duties, purchasers of duty-free spirits are maintaining the antiestablishment tradition of rum runners and whiskey boys.

My personal close out on the spirits section.

Rum.

We’ll talk about the last 3 beverages – coffee, tea, coca-cola – next week.

And remember,

in all that you do, please, don’t ever stop reading.